When psychologist Abraham Maslow died, he wasn’t quite finished with his famous hierarchy of human needs.

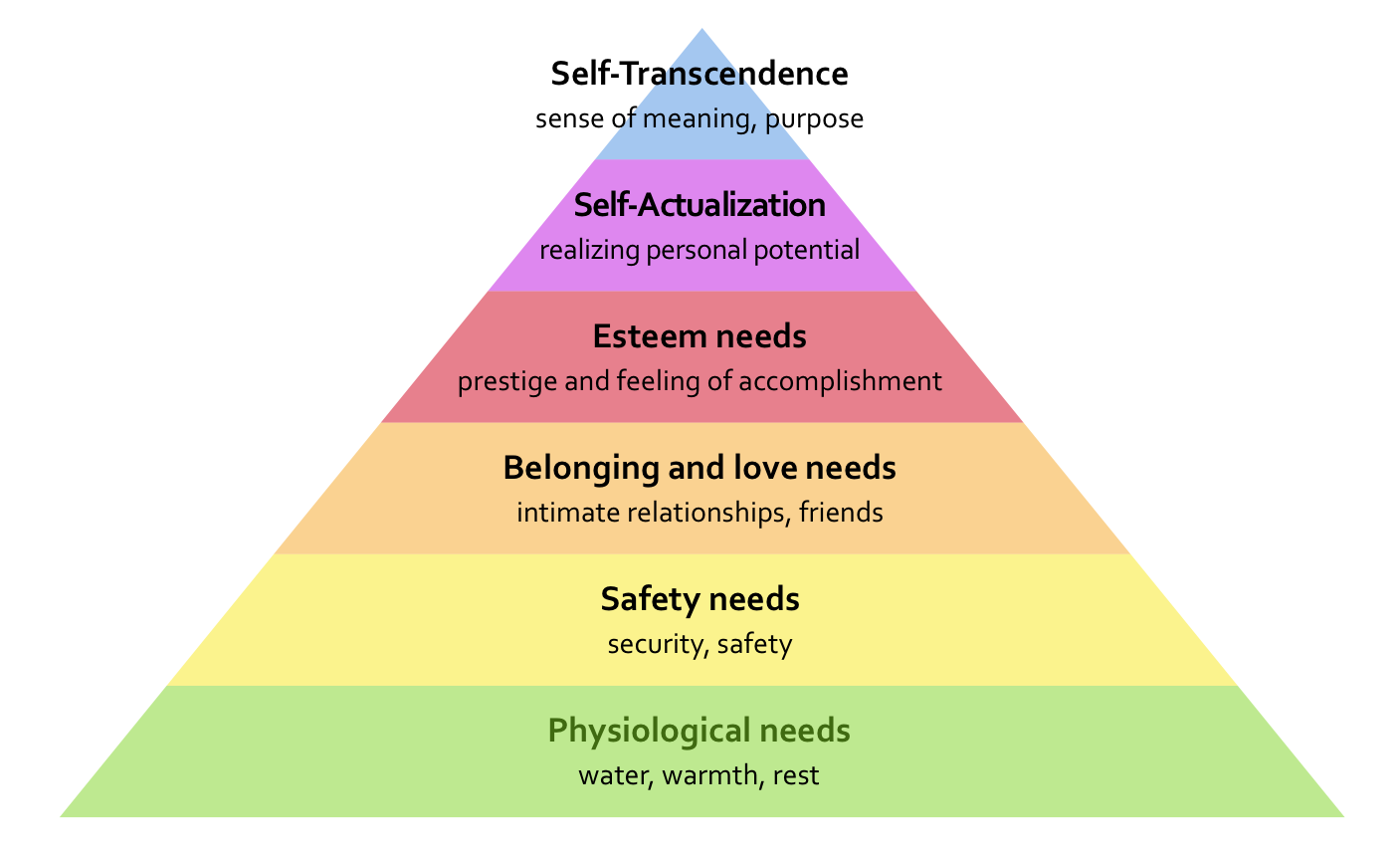

He’d presented his pyramid in a paper, “A Theory of Human Motivation” published in Psychological Review. Here’s the hierarchy as it seemed to him when it was published in 1943.

Maslow lived until 1970, though, and the pyramid above doesn’t represent his final thoughts on the matter. In his later years, he added a new apex to the pyramid: self-transcendence.

Nichol Bradford, CEO and founder of Willow Group, recently spent a summer at Singularity University, whose mission is to be “a global community using exponential technologies to tackle the world’s biggest challenges.” While there, she had the opportunity to hear talks by a stream of experts and forward-thinkers. At the end, she came away convinced that the most serious problems facing humanity aren’t technical: Although engineering our way out of trouble is possible, it can’t happen until we transcend ourselves, seeing beyond our own individual well-being to the needs of us all.

This is what the final stage of Maslow’s pyramid is about: Having met our basic needs at the bottom of the pyramid, having worked on our emotional needs in its middle and worked at achieving our potential, Maslow felt we needed to transcend thoughts of ourselves as islands. We had to see ourselves as part of the broader universe to develop the common priorities that can allow humankind to survive as a species.

Maslow saw techniques many of us are familiar with today — mindfulness, flow — as the means by which individuals can achieve the broader perspective that comes with self-transcendence. Given the importance of coming together as a global community, his work suggests that these methods and others like them aren’t just tweaks available for optimizing our minds, but vitally important tools if we hope to continue as a living species.

This article was reprinted with permission of Big Think, where it was originally published.