Researchers have found a way to turn stem cells into bone cells using only sound waves — a discovery that could help people regrow bone destroyed by disease.

Regrowing bone: While most of the cells in our body are specialized, stem cells can develop into all sorts of cells, and with the right conditions, they can help repair our bodies.

Patients who’ve lost bone to cancer or other diseases, for example, could have stem cells coaxed into becoming bone cells in the lab. These can be implanted at the site of the damage to prompt the growth of new bone.

The challenge: This is still an experimental procedure, and, unfortunately, the best way researchers have found to create the bone cells is to extract stem cells from a patient’s bone marrow, which is extremely painful.

Coaxing the stem cells into developing into bone cells also requires expensive, complicated equipment — that approach has made it difficult to scale up the treatment for use in the real world.

“Our device is cheap and simple to use.”

Leslie Yeo

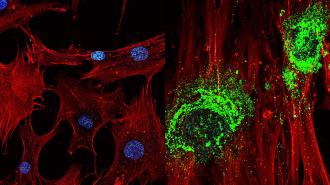

What’s new? Researchers at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) have developed a new technique that uses high-frequency sound waves to turn stem cells into bone cells.

According to their study, this approach is cheaper and faster, and it works with stem cells extracted from fat, which makes sourcing them easier and a far less painful experience for patients.

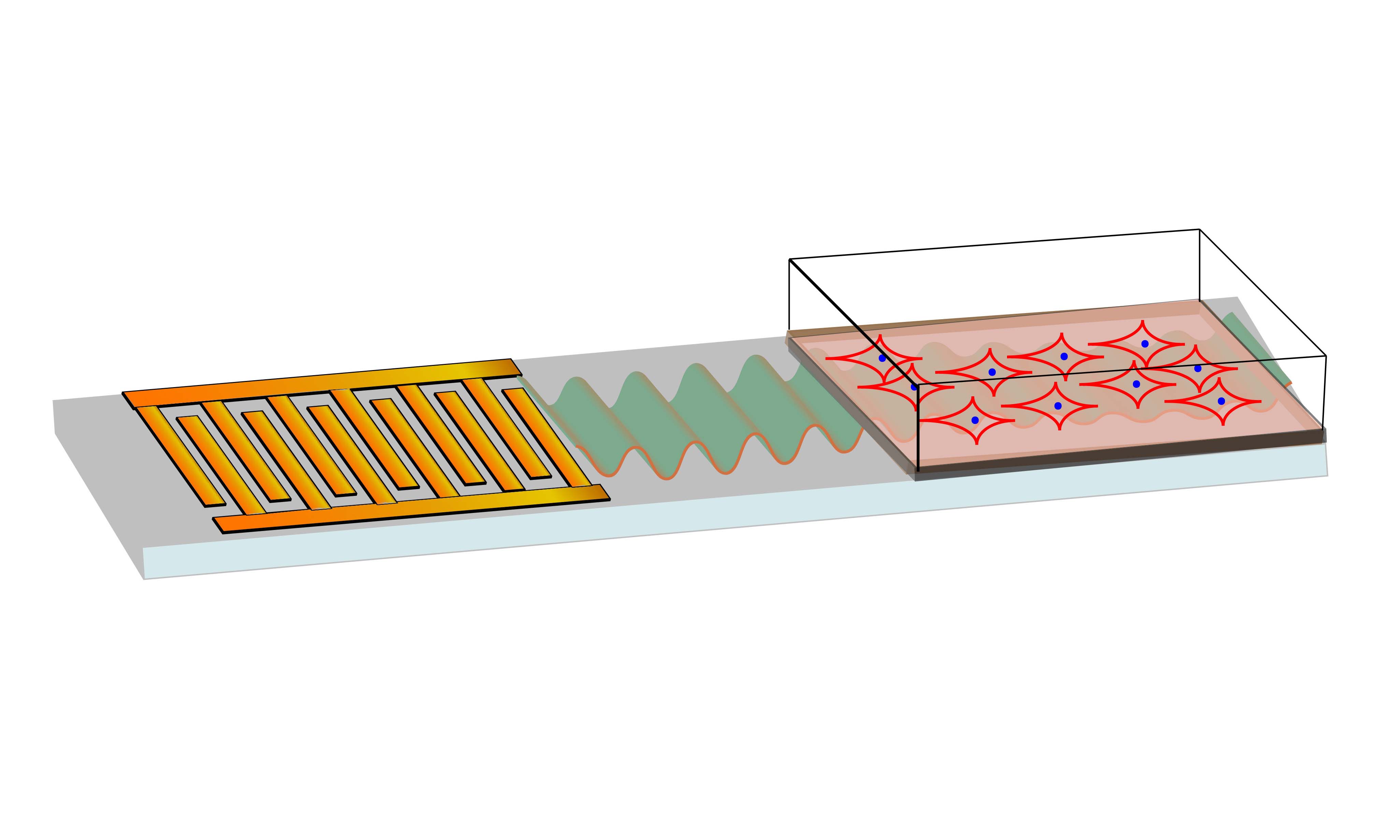

How it works: After more than a decade studying how high-frequency sound waves interacted with different materials, the RMIT team developed a low-cost microchip device that applies specific sound waves that will prompt stem cells to become bone cells.

“We can use the sound waves to apply just the right amount of pressure in the right places to the stem cells, to trigger the change process,” co-lead researcher Leslie Yeo said in a press release.

By applying the sound waves to stem cells for just 10 minutes a day, the researchers were able to coax them into becoming bone cells in as few as five days — several days faster than other techniques.

“This method also doesn’t require any special ‘bone-inducing’ drugs and it’s very easy to apply to the stem cells,” co-lead researcher Amy Gelmi said.

Looking ahead: The RMIT team is now looking at ways to scale up the technique. The goal is to one day use it to create cells that could be injected directly into a patient’s body or coated onto implants to help regrow bone.

“Our device is cheap and simple to use, so could easily be upscaled for treating large numbers of cells simultaneously — vital for effective tissue engineering,” Yeo said.

The big picture: The future of bone repair is looking bright.

While the RMIT looks for better ways to create bone cells from stem cells, others are developing better implants to host them. There are also groups exploring the use of 3D printing tech to inject cells precisely where they’re needed to repair a patient’s bones.

A radioactive bone cement could help prevent bone loss due to cancer, while a super-durable artificial enamel could one day be used to repair bones — leaving them even stronger than they were prior to sustaining damage.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].