Mice genetically engineered to lack the brain cells needed for smell were still able to sniff out cookies in their cages — thanks to replacement brain cells from a different species.

“This is the first time, to my knowledge, that the sensory system from one species could actually inform the behavior of another,” Kristin Baldwin, who led the research at Columbia University, told Fierce Biotech.

The challenge: Our brains are hugely complex, with hundreds of billions of neurons and countless networks between them, and there’s still so much about the organ we don’t understand, including how adaptable it is.

Animal studies can help fill in the gaps, but insights from them often don’t translate to people, and while experiments on human brain cells in a dish can be useful, they can’t replicate the complexity of the brain in its entirety.

All this makes it hard to treat the hundreds of diseases that affect the brain and develop technologies that can seamlessly and safely interact with it, like brain-computer interfaces.

Hybrid brains: Based on the new Columbia University study, brains may be more adaptable than we thought.

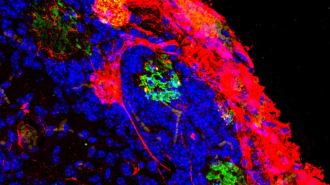

From previous research, the team knew that brains have a hard time integrating cells from another species if they’re introduced too late in development, so they inserted stem cells from rats into mice embryos that were only a few hours old.

“You could see rat cells throughout almost the entire mouse brain, which was fairly surprising to us.”

Kristin Baldwin

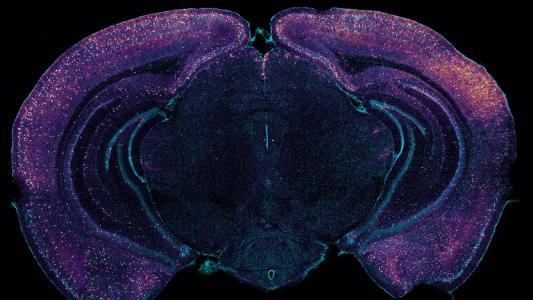

Even though rat brains typically develop at a slower rate than mouse brains, the rat cells followed the lead of their host, growing at the same speed as the mouse cells and forming connections in the mouse brain.

“You could see rat cells throughout almost the entire mouse brain, which was fairly surprising to us,” said Baldwin. “It tells us that there are few barriers to insertion, suggesting that many kinds of mouse neurons can be replaced by a similar rat neuron.”

Sniff it out: Animals with brain cells from two species have been created before, but the Columbia experiment was unique — testing whether they could prove that the mice were using and taking action based on input from the rat parts of their brains.

To do that, they genetically engineered the mice to either not have any olfactory neurons (the brain cells needed for smell) or to develop non-functioning versions. They also gave them hybrid brains created from rat cells.

“This is a type of model that hasn’t been available before.”

Kristin Baldwin

The researchers then hid cookies in the rodents’ cages to test whether they could use rat olfactory neurons to smell. The result: they could, with varying degrees of success — the mice with no mouse olfactory neurons did better than the ones that just had the neurons deactivated.

“This suggests that adding replacement neurons isn’t plug and play,” said Baldwin. “If you want a functional replacement, you may need to empty out dysfunctional neurons that are just sitting there, which could be the case in some neurodegenerative diseases and also in some neurodevelopmental disorders like autism and schizophrenia.”

Looking ahead: The Columbia team couldn’t control where the rat cells turned up in the mice, which meant each mouse born of their research was slightly different from the others — figuring out how to exert more control over the distribution of the cells is a goal of future studies.

Ultimately, they believe their approach could one day be used to create animals with all kinds of hybrid brains, potentially even ones with human brain circuits, which could be invaluable for testing treatments for human brain diseases and new brain tech.

“At least with these models, we can try to do a lot of different experiments at a lower cost than a clinical trial,” Baldwin told Fierce Biotech. “This is a type of model that hasn’t been available before.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].