In Google Maps, drag Pegman over Europe and you’ll see a curious picture emerge: Virtually the entire continent is covered in the blue lines that indicate Street View is available, but Germany and Austria are almost entirely blank.

Regions unknown

It is an image reminiscent of those late-19th-century maps of Africa with the center of the continent left empty, marked “Regions Unknown.” Germany and Austria are among the world’s most advanced economies, so why do Google’s camera cars find those countries as inaccessible and/or inhospitable as European explorers found Africa’s interior?

The reason is that Germans are famously protective of their privacy — an attitude that also resonates with their culturally close neighbors in Austria. But it all depends on what you mean by “privacy.” For example, Germans are not that private about their private parts.

Totalitarian traumas

While public nudity is a big no-no in the United States, for example, Germany has a long tradition of what is known as FKK — short for Freikörperkultur, or “free body culture.” Certain beaches and areas of city parks are dedicated to nude sunbathing, and even Nacktwanderung (“nude rambling”) is a thing.

On the other hand, Germans are extremely possessive of their personal data — and they’re shocked by the readiness with which Americans (and others) share their names, addresses, friends’ lists, and purchase histories online.

According to research presented in the Harvard Business Review, the average German is willing to pay as much as $184 to protect their personal health data. For the average Brit, the privacy of that information is only worth $59. For Americans and Chinese, that value drops to single-digit figures.

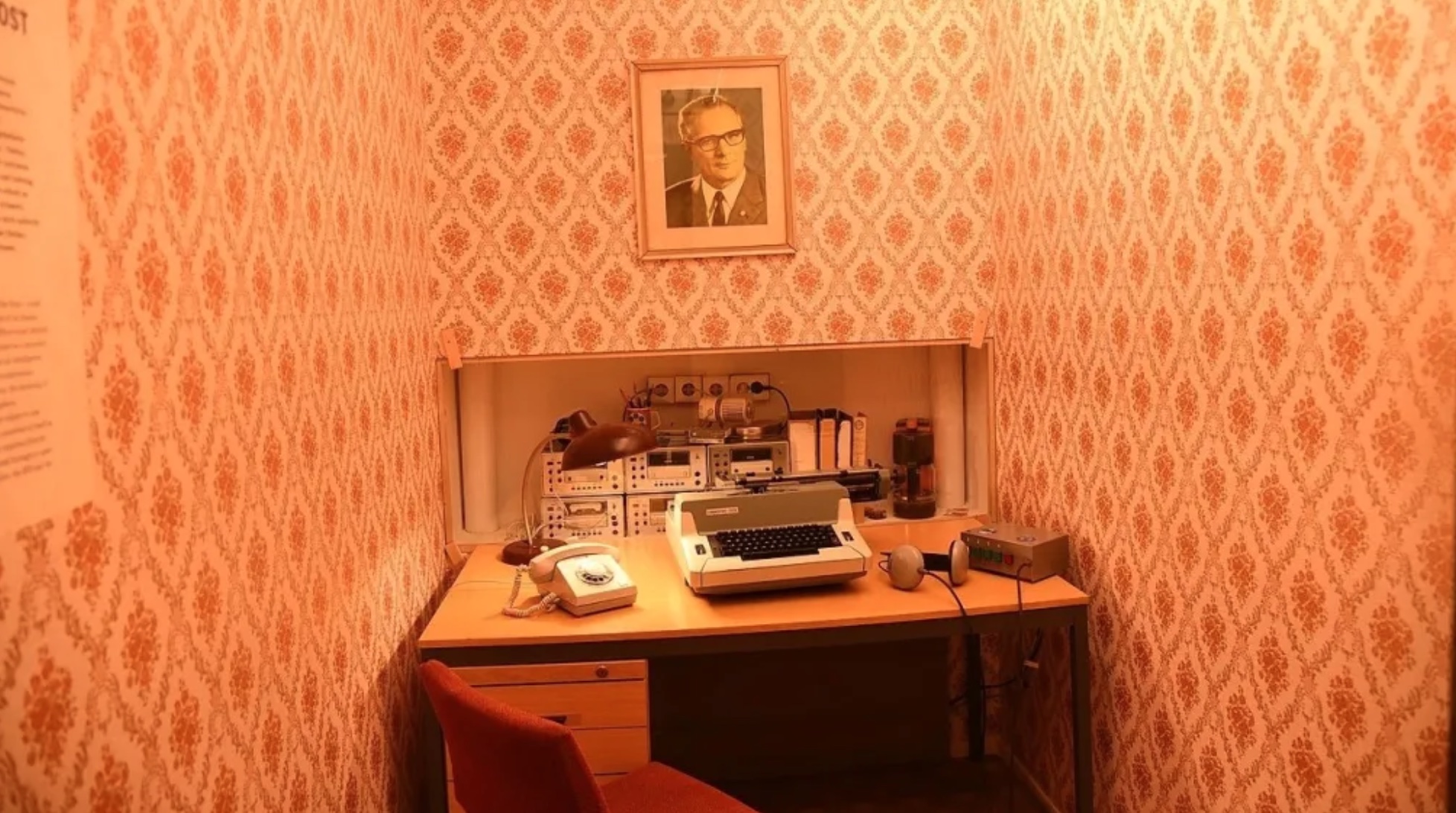

Why? Because Germans carry the trauma of not one, but two totalitarian systems in their recent past: the fascist Third Reich, and communist East Germany.

Nie wieder

Both regimes wanted total control over their citizens. In the Nazi years, the state’s blunt instrument was called the Gestapo (short for Geheime Staatspolizei, or “secret state police”). In East Germany, it was the Stasi (short for Staatssicherheit, or “state security”).

In both systems, citizens effectively ceased to have a right to privacy, and could be branded criminals for private thoughts or acts, resulting in severe punishment. As with many other aspects of the Nazi regime, post-war Germany resolved Nie wieder(“Never again”) when it came to violations of privacy. That’s one of the reasons why the very first article of (then still only West) Germany’s post-war constitution reads:

Human dignity shall be inviolable. To respect and protect it shall be the duty of all state authority.

Informational self-determination

Over the decades, Germany broadened and deepened its definition of privacy.

- In 1970, the German state of Hesse passed the first data protection law in the world.

- In 1979, West Germany laid the foundation for the Bundesdatenschutzgesetz (BDSG), or Federal Data Protection Act, the main aim of which was to protect the inviolability of personal, private information.

- In the 1980s, citizens successfully sued the government over a census questionnaire so detailed it would allow the government to identify individuals. The court recognised German citizens’ right to “informational self-determination” and block the sharing of any personal information with any government agency or corporation.

- In March 2010, the German Federal Constitutional Court overturned a law that allowed the authorities to store phone and email data for up to six months for security reasons, as a “grave intrusion” of personal privacy rights.

- In May 2018, the EU adopted the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which follows the German model of data discretion rather than the laxer American one.

Missing the train

Foreign firms operating in Germany have to adjust to some of the strictest privacy laws in the world. But Nie wieder is difficult to maintain in a world that increasingly mines and monetises data. As a result, the inexorable advance of digitization is viewed with a mixture of fatalism and misgiving.

Example one: Germany’s split personality when it comes to social media. Yes, Germans are instinctively distrustful of big tech companies such as Google and Facebook. Meanwhile, Google has cornered more than 90% of the search engine market in Germany, and close to half of all Germans have a Facebook account.

Example two: privacy trumps efficiency. While Germany’s macro-economy relies on high tech to maintain its global pole position, good old-fashioned cash is still king on a microeconomic level. In 2016, 80% of all point-of-sale transactions in Germany were made in notes and coins rather than via card. In the Netherlands, it was just 46%.

Brits, Danes, or Swedes can go for months without handling cash. In Germany, you won’t last a day. Why? Again, an intense desire for privacy and an instinctive distrust of surveillance. A cashless society would be more transparent and efficient, but also a lot less private.

If there’s one thing Germans value even more than efficiency, it is — you guessed it — privacy. Germany seems in no hurry to catch the digitization train, when other countries are stations ahead, and generating measurable benefits.

“A million-fold violation”

Case in point: Google Street View’s German debacle. Launched in the U.S. in 2007, Google Street View’s mapping of interactive roadside panoramas has since expanded to cover most of the world.

In June 2012, it had mapped 5 million miles of roads in 39 countries; by its 10th anniversary in May 2017, the total was 10 million miles in 83 countries.

Street View features places as far off the beaten path as the International Space Station, gas extraction platforms in the North Sea, and the coral reefs of West Nusa Tenggara in Indonesia. But not the Weimarer Strasse in Fulda, or most other normal streets in Germany and Austria, for that matter.

Not for lack of trying. In August 2010, Google announced that it would map the streets of Germany’s 20 biggest cities by the end of that year. The outrage was huge. Some of Google’s camera cars were vandalized. A 70-year-old Austrian who didn’t want his picture taken threatened the driver of one with a garden pick.

Ilse Aigner, Germany’s minister for Consumer Protection at the time, called Google’s “comprehensive photo offensive” a “million-fold violation of the private sphere (…) There is not a secret service in existence that would collect photos so unabashedly.”

Blurry Street

Google automatically blurs faces and vehicle license plates and, upon request, the fronts of houses. Fully 3% of households in the relevant areas requested their houses to be blurred. Faced with that unprecedentedly high level of resistance, Google in 2011 published the data already collected, but left it at that.

Following the revelation in May 2010 that Google had used data from unencrypted wifi connections when collating its roadside panoramas, Street View was banned from Austria. From 2017, Google has resumed collecting imagery in Austria, and from 2018, it is available for selected localities.

As younger generations become more familiar with the transactional aspect of their personal data, perhaps German attitudes toward data privacy will start shifting significantly toward the American model.

For now, the difference has one side of the argument at a distinct disadvantage. As one online commenter noted: “It doesn’t seem quite fair that anyone in the world including Germans can take a virtual stroll around my street and my city, but I can’t do the same in their country.”

This article was reprinted with permission of Big Think, where it was originally published.