This article is an installment of Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Thursday morning by subscribing here.

A startup’s metal 3D printing process could potentially cut the cost of manufacturing cars, consumer tech, and more — while also making the production process less wasteful.

3D printing 101: 3D printing is an additive process — layers of “ink” are stacked one on top of the other in a precise pattern, and when they dry, you’re left with a solid, three-dimensional object.

3D printing typically allows for more design versatility and produces less waste.

This approach allows for far more design versatility than standard manufacturing methods, which can save on costs — instead of manufacturing multiple parts that then have to go through an assembly process, you can print a finished product in one step.

3D printing also results in less waste than standard “subtractive” manufacturing processes, which involve chipping away at a larger piece of material until you’re left with the desired shape — and all those removed bits end up in the trash or have to be recycled to be useful again.

The status quo: The most common material used for 3D printing is plastic, because it’s cheap, malleable, and has a low melting point. But special machines can be used to print with other materials, including dirt, wood, concrete, gel, lab-grown meat, living cells, and more.

You can also 3D print objects out of metal, most commonly with a technique called “powder bed fusion (PBF).”

Metal 3D printing isn’t yet fast enough to compete with standard production methods.

In this process, a thin layer of metal powder is laid across the bed of the “printer,” and then a laser melts the metal powder in the desired pattern. A new layer of powder is added on top of the first. The process with the laser repeats, and the newly melted powder fuses to the metal below it.

When the printing is complete, all the loose powder is dusted off (to be used again later), and you’re left with a solid metal object.

Scaling up: Metal 3D printing like this just isn’t fast enough to compete with standard production methods, for most products, even after adding extra lasers to the machine.

As a result, the benefits of metal 3D printing have remained largely untapped on the factory level — but startup Seurat Technologies thinks it can change that.

Area Printing is 10 times faster than other laser-based metal 3D printing tech and 50% cheaper.

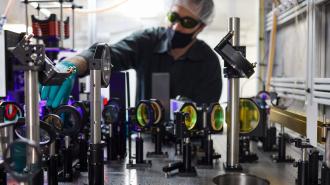

Seurat Technologies

The company has developed a technique called Area Printing that splits a single, powerful laser beam into more than two million “pixels.” The laser can then be programmed to melt (or not) the metal powder being hit by each pixel in its beam at one time, allowing it to cover a much larger area more quickly.

According to Seurat’s website, the technique is already 10 times faster than other laser-based PBF technologies and 50% cheaper. By 2025, the startup anticipates it being 100 times faster.

Looking ahead: In January, Seurat announced that it had raised another $21 million, bringing its total funding to $79 million — investors include Xerox Ventures, Porsche Automobil Holding SE, and Capricorn’s Technology Impact Fund.

Seurat plans to launch its first commercialization program in 2022 and says seven major automotive, aerospace, energy, consumer electronics, and industrial companies have already signed letters of intent to join.

“We are working with the world’s largest manufacturers in migrating their designs to Area Printing to help them gain lead-time, cost, and quality advantages, while making a positive environmental impact,” CEO James DeMuth said.

The big picture: Seurat isn’t the only company trying to bring metal 3D printing to mass manufacturing.

Australian startup Spee3D has developed a system that shoots metal powders at a base with such speed that they fuse together to form a 3D object, while San Francisco’s Mantle thinks it can scale the tech by 3D printing objects in a more traditional fashion using a metal paste.

It’s still too soon to say whether any of these technologies will be able to replace current manufacturing processes.

That doesn’t mean we won’t be seeing more metal 3D printing in the future, though — the tech is still incredibly useful for both prototyping new metal objects and manufacturing specialized parts for rockets, nuclear reactors, and more.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].