Cambridge-based biotech Synlogic’s bacteria-based treatment for phenylketonuria (PKU) has shown positive results in a small phase 2 trial, the company announced in October — a proof-of-concept for the idea of using engineered strains of beneficial bacteria to treat disease.

“Diseases like PKU are good low-hanging fruit to answer the first question, which is whether the bacteria can do something that benefits the individual,” UC San Diego gastroenterologist Amir Zarrinpar told WIRED’s Emily Mullin.

More researchers have been turning to bacteria as potential therapies as of late.

Biotech Synlogic’s bacteria-based treatment for phenylketonuria (PKU) has shown positive results in a small phase 2 trial.

MIT and Harvard have modified a strain of bacteria used in cheese making to help protect the ecosystem of beneficial bacteria in the gut, called the microbiome, which can be devastated by medications and potentially lead to infections.

University of Georgia researchers have engineered E.coli to produce L-DOPA, a tried-and-true Parkinson’s therapy whose short half-life they hope to overcome by tuning the bacteria into little L-DOPA factories.

What is PKU? Patients with PKU (“phenyl-keto-nuria”) cannot break down an amino acid called phenylalanine, or PHE, usually found in foods filled with protein. Eating too much protein — or the sugar sub aspartame — causes PHE to build up to toxic levels, which can cause severe brain damage.

As a result, patients must be put on a severely restricted diet for essentially their entire lives; it’s serious enough that babies in the US and many other countries are screened for PKU soon after being born.

“The types of foods that they are able to eat are extremely limited,” Jessica Kopesky, a Children’s Wisconsin clinical dietician who sees PKU patients, told Mullin.

“Any new medical advancement that is able to help bring down Phe levels and potentially allow them to eat even a little bit more protein from food will have a large impact on the types of foods these patients can eat and the flexibility that they have in their day-to-day lives.”

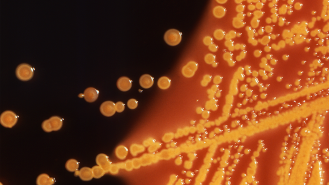

Engineering E.coli: For their drug candidate, Synlogic turned to a strain of gut bacteria called E. coli Nissle, which naturally protects against dysentery. These beneficial bacteria were modified to also reduce levels of PHE, picking up where the body left off.

“Similar to how you might program a computer, we can tinker with the DNA of bacteria and have them do things like produce a drug at the right time and the right place, or in this case, break down a toxic metabolite,” Synlogic cofounder Timothy Lu told Mullin.

The bacteria was able to reduce levels of an amino acid that can cause brain damage in PKU patients when it builds up.

The small, 28-day, open label phase 2 trial — designed to test the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of two different bacterial candidates — enrolled 20 phenylketonuria patients, who drank a liquid mixture of one or the other bacteria.

Both strains showed reductions in bloodstream PHE levels that Synlogic deemed “clinically meaningful” by day 14 — a 20% reduction in baseline PHE for one bacterial strain (SYNB1618) and a 34% reduction for the other (SYNB1934).

Those results were similar for those taking sapropterin, a phenylketonuria medication that helps break down PHE, as well, suggesting that the two could one day work in concert, Synlogic said.

Adverse events were mild or moderate, the biotech said, and tended to be GI-related.

The full results have not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal; Synlogic will present the full data at upcoming medical meetings and will submit it for review and publication.

The more promising of the two strains, SYNB1934, will move into a phase 3 trial scheduled to begin in 2023, with the intent of gathering enough data to file for approval.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].