Even when the drug he worked on prevented infections in volunteers purposefully injected with malaria in the lab, the NIH’s Robert Seder told Science that he wasn’t popping the champagne yet. He’d let the bubbles flow when there was data proving it worked in the field.

Well, go get some Dom, Dr. Seder.

A phase 2 clinical trial of the NIH’s malaria-blocking monoclonal antibody protected adults over the 6-month malaria season in Mali. The antibody, called CIS43LS, was 88.2% effective at preventing infection over a 24-week period.

The study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, tested the safety and efficacy of a single infusion of the monoclonal antibody, or mAb, aimed at Plasmodium falciparum, the malaria parasite most likely to cause severe — and potentially fatal — infection.

A phase 2 clinical trial of the NIH’s malaria-blocking monoclonal antibody was 88.2% effective at preventing infection in adults during Mali’s malaria season.

The results were presented at the American Society of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene 2022 Annual Meeting in Seattle.

“These study results suggest that a monoclonal antibody could potentially complement other measures to protect travelers and vulnerable groups such as infants, children, and pregnant women from seasonal malaria and help eliminate malaria from defined geographical areas,” NIAID director Anthony Fauci said.

A buzzing burden: Malaria is transmitted via the bite of infected mosquitoes. Despite being curable, malaria’s disease burden is still high, and especially in developing countries.

The WHO estimated that in 2020, there were 241 million cases of malaria around the world, with around 627,000 deaths. Africa bore the lion’s share of that terrible burden — 95% of the infections and 96% of the deaths, with children under five accounting for 80% of the fatalities.

While there is now a WHO-recommended vaccine and a number of small chemical compounds that can fight off malaria, their efficacy is only moderate, and they require multiple rounds of dosing — not ideal — and the parasite has shown a propensity for drug resistance.

This has researchers racing for other weapons in the fight.

“These first field results demonstrating that a monoclonal antibody safely provides high-level protection against intense malaria transmission in healthy adults pave the way for further studies to determine if such an intervention can prevent malaria infection in infants, children, and pregnant women,” Seder said.

“We hope monoclonal antibodies will transform malaria prevention in endemic regions.”

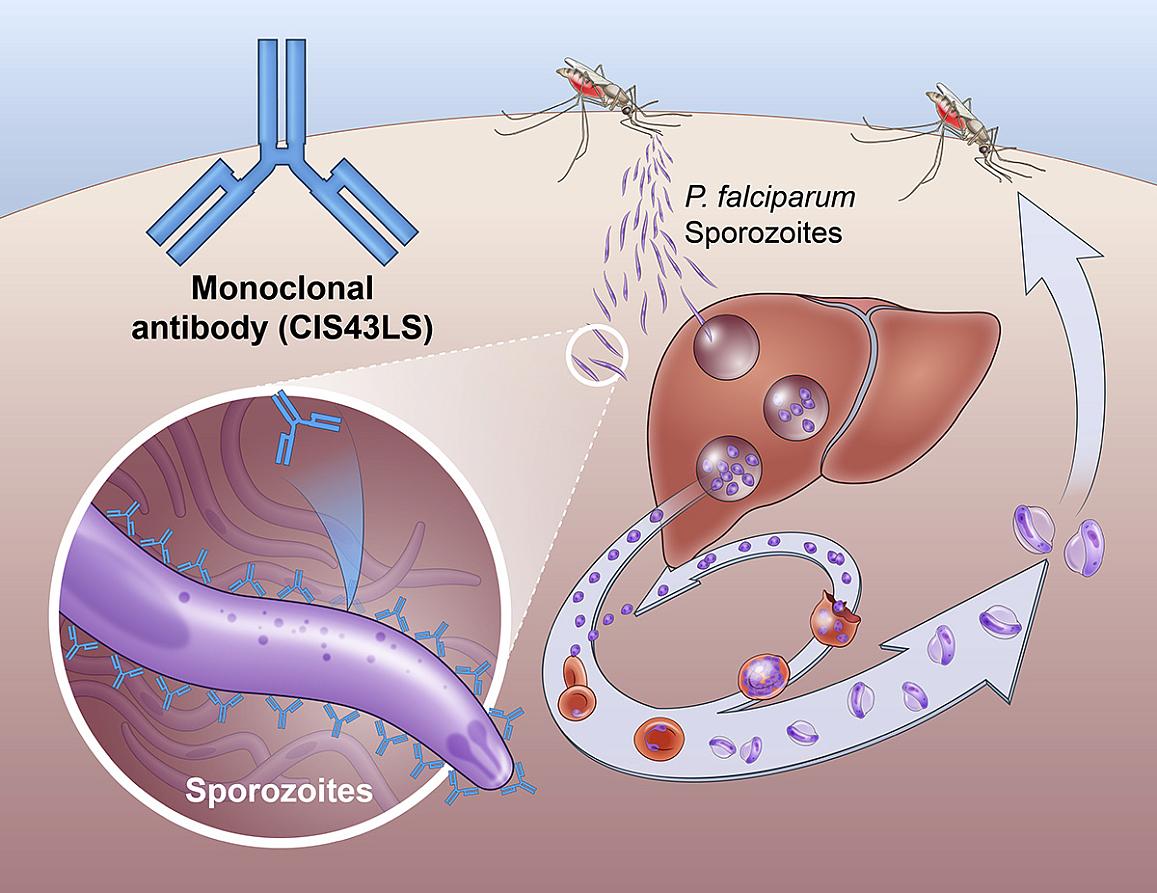

Making a malaria mAb: The antibody, which was first found in a person who had received an experimental malaria vaccine, works by throwing a wrench in the life cycle of P. falciparum.

When a mosquito first bites a person, the parasite is in a life stage known as a “sporozoite,” which the antibody sticks to and neutralizes, preventing it from causing disease.

The trial enlisted 369 healthy, non-pregnant adults between 18 and 55 from rural communities in Mali, Kalifabougou and Torodo, which can be ravaged by malaria during Plasmodium season, from July through December.

There were two parts to the trial.

In the first, the researchers wanted to assess the safety of three different doses of the antibody. They split 18 people into three groups of six, with each getting a different dose for their infusion — 5 milligrams per kilogram of body weight, 10 mg/kg, or 40 mg/kg. After 24 weeks, it was determined that all dosages were safe and tolerable.

The second part of the trial was to determine how well the 10 mg/kg and 40 mg/kg protected against Plasmodium versus a placebo, with 330 people randomized into groups so that both they and the researchers did not know who was receiving what.

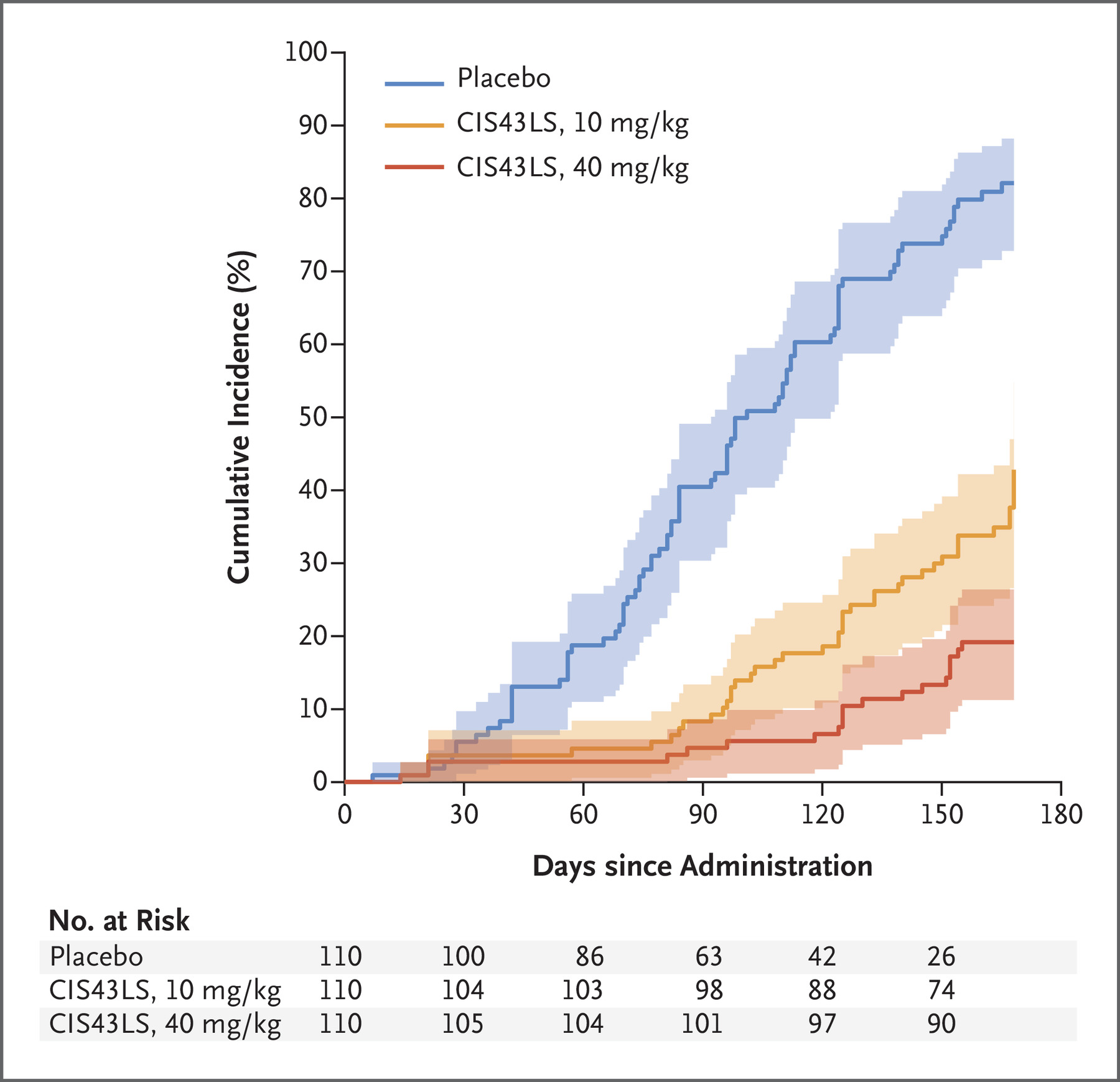

There were two different measures for protectiveness, both measured across the 24-week study.

The first looked at protection up until the first infection, and found the 40 mg/kg dose to be 88.2% effective at preventing infection, and the 10 mg/kg dose 75% effective.

The second looked at the proportion of people infected at any point over the 24 weeks, and determined the higher and lower doses to be 76.7% and 54.2% effective at preventing infection, respectively.

A second possibility: Seder and company have also developed a different antimalarial mAb, dubbed L9Ls, described by the NIH as “much more potent.” This stronger antibody could be given at smaller doses and via injection under the skin instead of an IV infusion, potentially making it a better option for the developing countries that bear the brunt of malaria’s wrath.

An early trial found L9Ls to be effective in adults in a controlled setting, but two larger phase 2 trials testing it in adults, children, and infants have begun in Mali and Kenya.

“We need to expand the arsenal of available interventions to prevent malaria infection and accelerate efforts to eliminate the disease,” Fauci said.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].