A new brain mapping study out of Australia found that the brains of people with mental illnesses vary widely — but it also identified commonalities that could lead to better treatments.

Mental illnesses: At any given time, more than 20% of American adults are living with a mental illness — disorders that affect how people think, feel, or behave — according to the National Institute of Mental Health.

While many medications can alleviate the symptoms of the most common mental illnesses, such as depression, the brain is incredibly complex, and a drug that helps one person might actually make another feel worse, even though they’ve been diagnosed with the same disorder.

People with mental illnesses tend to have smaller brain volumes than the rest of the population.

What’s new? Identifying brain abnormalities shared by many people with the same symptoms could lead to treatments that work for more patients with the same underlying brain physiology.

Past studies have shown that, on average, people with mental illnesses tend to have smaller brain volumes than the rest of the population, so a team from Monash University decided to tug on that thread in a new study published in Nature Neuroscience.

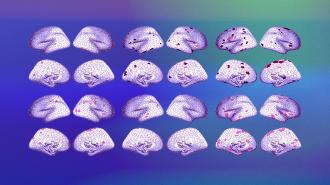

Brain mapping: Using statistical models and scans from nearly 1,500 healthy people, the researchers determined how large more than 1,000 parts of the brain typically should be, based on a person’s age and sex — kind of similar to the height and weight charts used by pediatricians.

They then compared brain scans from nearly 1,300 people with six different mental illnesses (schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, or autism spectrum disorder) to their volume standards.

The idea was to see whether particular mental disorders were associated with structural changes in specific parts of the brain.

“Specific brain regions showing large deviations in brain volume vary a lot across individuals.”

Alex Fornito

Not so simple: While many patients had brain volumes that differed from those of mentally healthy people, how they differed varied significantly, even between people with the same official diagnosis.

“We confirmed earlier findings that the specific brain regions showing large deviations in brain volume vary a lot across individuals, with no more than 7% of people with the same diagnosis showing a major deviation in the same brain area,” said lead researcher Alex Fornito.

“This result means that it is difficult to pinpoint treatment targets or causal mechanisms by focusing on group averages alone,” he continued. “It may also explain why people with the same diagnosis show wide variability in their symptom profiles and treatment outcomes.”

Circuits, not spaces: While people with the same mental illnesses often had abnormalities in different regions, those regions did tend to be part of the same brain circuits, meaning they often work together, sending signals between one another.

This suggests that the circuits may be worthwhile targets for future treatments.

“It’s possible that this circuit-level overlap explains commonalities between people with the same diagnosis, such as, for example, why two people with schizophrenia generally have more symptoms in common than a person with schizophrenia and one with depression,” said researcher Ashlea Segal.

“The ultimate goal would be to develop these more customized therapeutic approaches.”

Alex Fornito

The big picture: Eventually, it might be possible for doctors to use the Monash team’s framework to see how a patient’s brain differs from the average for mentally healthy people and then prescribe treatments most likely to help them.

“We still have a fair amount of work to go before we can use this information and really understand what it means clinically, but…the ultimate goal would be to develop these more customized therapeutic approaches,” Fornito told ABC News in Australia.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].