“It was an accidental finding by Alexander Fleming that led to the golden age of antibiotics, but now that’s nearing the end because of antibiotic-resistant bacteria,” Lloyd Miller, a former professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, said.

“It seems fitting that another surprise in the lab could be the start of a second golden age, the use of host-directed immunotherapy.”

Miller is comparing Fleming’s finding — the discovery of penicillin — with what he hopes will be a similar watershed moment in the invisible, forever war with infectious disease.

In a fortuitous turn of events, the scientists discovered that, by blocking enzymes called caspases, they can enhance the immune system, fighting off even drug-resistant bacteria without antibiotics.

By preventing the enzymes from taking immune system cells out of action, mice were able to beat MRSA without additional medication.

“It’s like a fire department where older firetrucks are kept operating to help put out blazes, when otherwise, they would have been taken out of service,” Miller said.

Attack of the superbugs: In 1928, Fleming came back to his lab from vacation and found that the mold penicillin, blown in from an open window, had stopped the growth of staph bacteria in his Petri dish. It set in motion a revolution in medicine, which tipped the scales in the war on infectious disease in humanity’s favor.

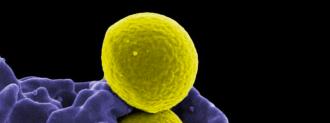

But given such a powerful tool, we immediately began to abuse it. Indiscriminate use of antibiotics allowed only the strongest, most resistant bacteria to survive. Now, hardened by decades of denying death, these “superbugs” — bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics — are proving a public health threat.

“It seems fitting that another surprise in the lab could be the start of a second golden age, the use of host-directed immunotherapy.”

Lloyd Miller

The race is now on to find new ways to stop them, with novel antibiotics, like CDB or dragon’s blood. But any antibiotic will eventually lead to resistance, so scientists are also looking at other ways of surviving infections, without drugs.

A happy accident: The Hopkins researchers wanted to play around with the immune system to see if they could figure out how the body could beat an aggressive infection, called MRSA, without drugs.

They started by breaking something to see how it works. They wanted to see what would happen if mice lost the ability to manufacture a protein, called interleukin-1 beta, that helps immune cells fight bacteria.

That protein is activated by a caspase enzyme. “We gave the mice a blocker of all caspases” to see if that would make the mice more vulnerable to MRSA, Miller said.

To their surprise, the result was exactly the opposite.

With all their caspase enzymes blocked, the mice mounted a “rapid and remarkable” immune response against MRSA, clearing the infection without antibiotics.

What happened? By preventing the enzymes from doing their job, the researchers accidentally stopped the body from clearing old, damaged cells (a process called apoptosis). This meant fewer immune system cells were being taken out of service, and so more were able to continue the fight against MRSA.

Even weirder, blocking caspases also led to an increase in a different type of cell death, called necroptosis. This killed off other immune cells called macrophages, the white blood cells you likely picture when you think of the immune system.

The mice mounted a “rapid and remarkable” immune response against MRSA, clearing the infection without antibiotics.

But those dead macrophages enhanced the mice’s ability to fight the infection. (The immune system, alas, is the graveyard of intuition.)

“The destruction of macrophages by necroptosis releases large amount of tumor necrosis factor, or TNF, a protein that triggers bacteria-fighting immune cells to swarm into an infected area of skin,” Hopkins dermatology postdoc Martin Alphonse said in the release.

Combined, the effect of blocking every caspase led to a stronger immune response, capable of knocking the MRSA skin infection out in the mice.

The technique also helped mice more effectively fight off two other dangerous bacteria, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Streptococcus pyogenes, which can cause scarlet fever, toxic shock syndrome, and flesh-eating disease.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].