Bioengineers at UCLA are developing an AI-powered wearable that could allow people with vocal cord problems to talk.

“This new device presents a wearable, non-invasive option capable of assisting patients in communicating during the period before treatment and during the post-treatment recovery period for voice disorders,” said lead researcher Jun Chen.

The challenge: At some point in their lives, about one in three people will have a problem with their vocal cords that prevents them from being able to speak naturally — laryngitis, vocal cord paralysis, and recovery from throat surgery all can impact people’s ability to talk.

Though the loss is often temporary, not being able to talk can have a significant impact on a person’s job and quality of life, and existing workarounds, such as electrolarynxes — devices you hold to your throat when you want to speak — can be cumbersome, at best.

The AI-powered wearable predicts which sentence the person is trying to say.

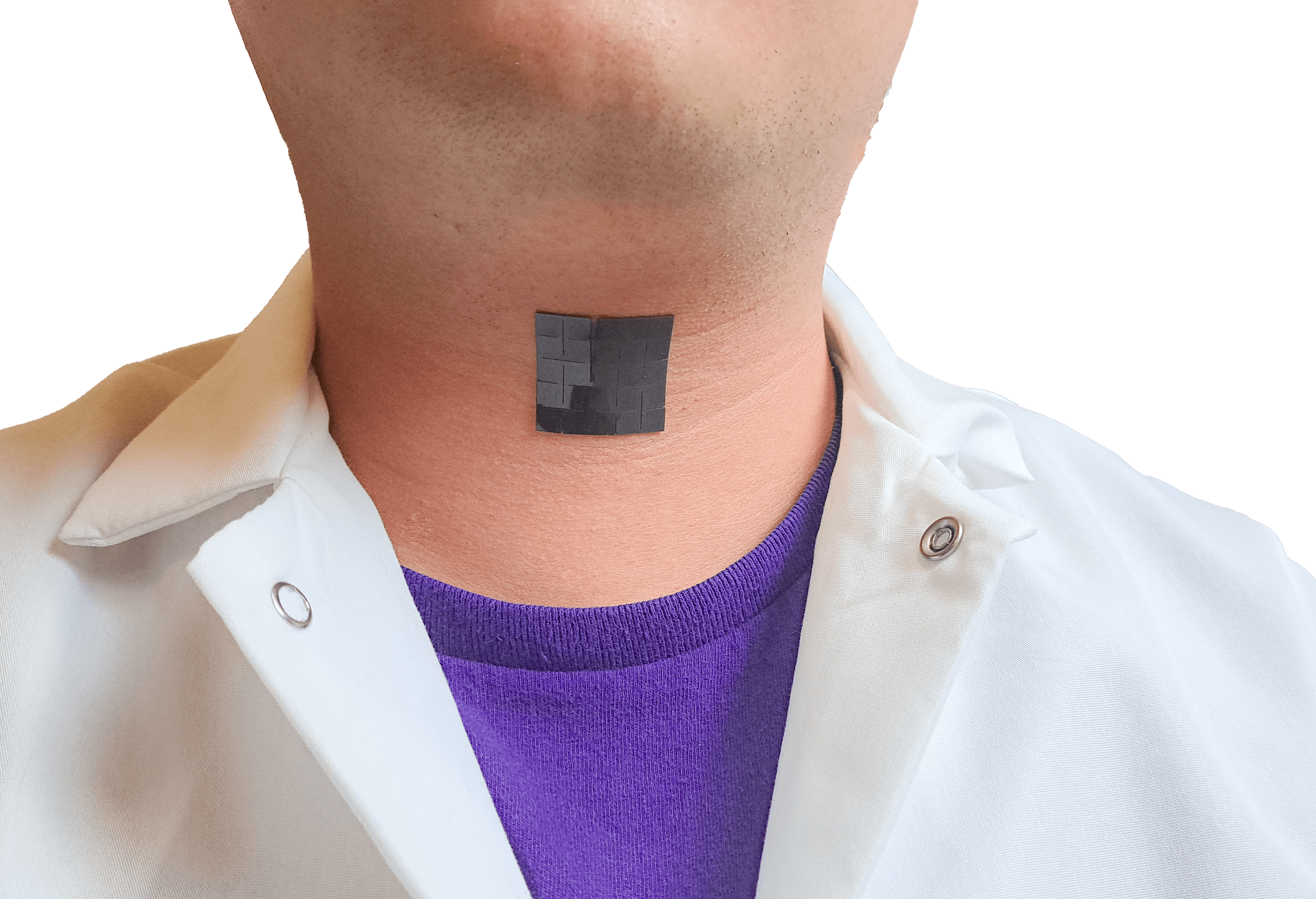

What’s new? The UCLA team’s AI-powered wearable could be a more convenient option. It’s about twice the size of a postage stamp and attaches to the front of the throat using double-sided tape — no need to hold anything.

When a person tries to talk, the movement of their larynx muscles applies a mechanical force to the device. This disrupts a magnetic field generated by the wearable, and that disruption is translated into electrical signals that are sent to an algorithm.

The algorithm predicts which of a predetermined set of sentences the person is trying to say. It then triggers a part of the wearable that functions as a speaker, prompting it to play pre-recorded audio of the sentence.

The details: To train this algorithm, the UCLA team had volunteers repeat five sentences 100 times each — voicelessly, like they were lip syncing — while wearing the device. The AI then learned to associate each sentence with certain electrical signals.

When the team tested the AI-powered wearable by having each volunteer voicelessly repeat the sentences another 20 times, they found it could correctly predict which sentence they were trying to say 95% of the time.

Looking ahead: Being able to “say” just five sentences might not be terribly useful, especially if a person is going to be without their voice for an extended period of time, but first author Ziyuan Che told Freethink he believes the team would be able to update the system to “translate every sentence the user pronounces” if they teamed up with AI experts.

“Since our lab is a device research lab, we have used a very simple classify algorithm to demonstrate the application … With [an] algorithm with an encoder-decoder structure, we would be able to decode every laryngeal movement to a syllable,” he said.

The AI’s predictions were correct 95% of the time.

Che told Freethink the team has also tested the feasibility of running the algorithm for the AI-powered wearable on microcontrollers and machine learning chips, which could eliminate the need for an external device for processing in the future — everything could happen on the device itself.

For now, though, the researchers are focused on expanding their current algorithm’s vocabulary and testing it in people with speech disorders, demonstrating its potential to one day help people have their voices heard, even if their vocal cords aren’t cooperating.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].