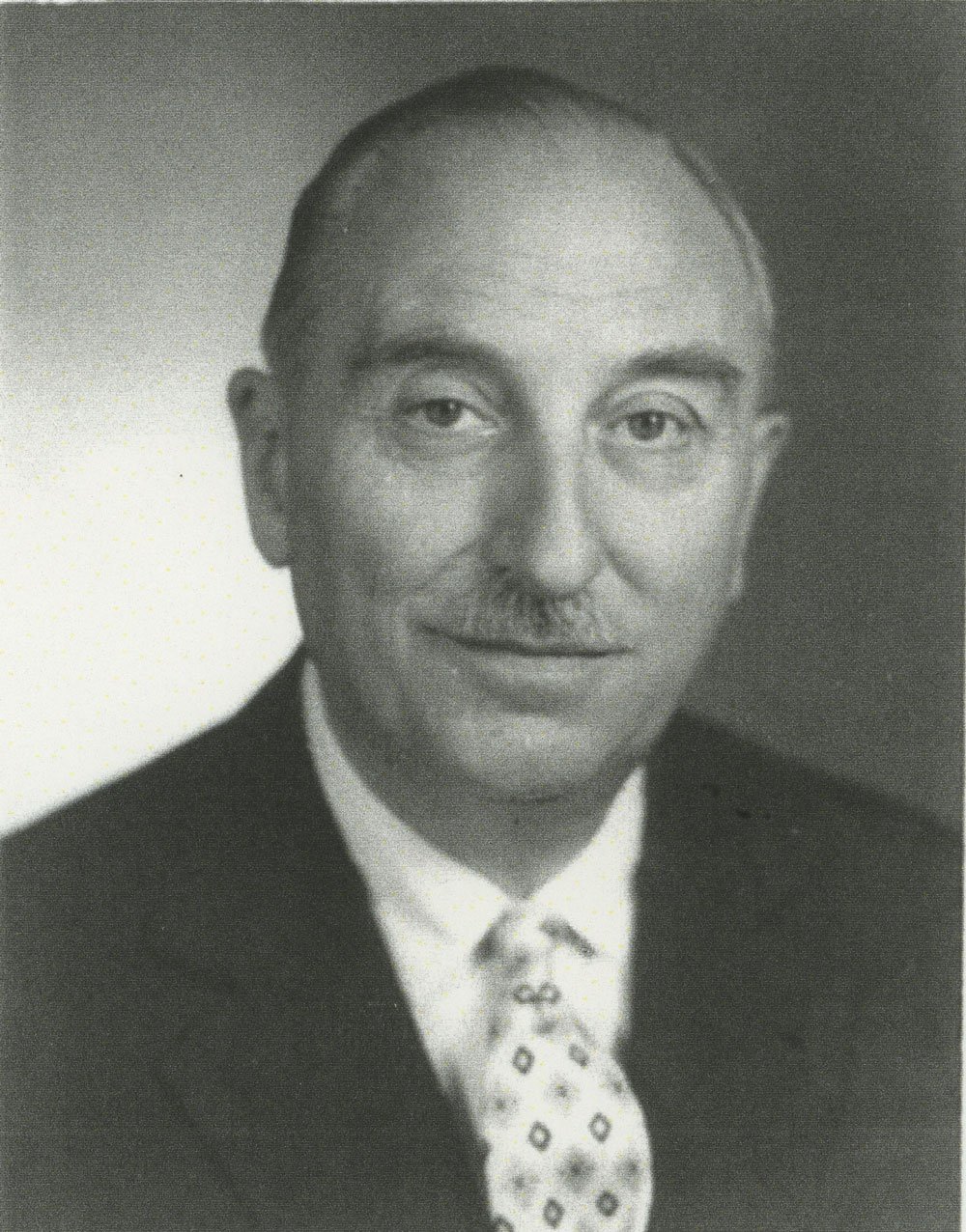

When Nazi soldiers raided Rome’s Fatebenefratelli Hospital in May of 1944, Dr. Giovanni Borromeo was able to stop them from taking the Jewish families hiding there without firing a single shot. He told the soldiers that the Jews in his care were sick with a highly contagious and deadly illness called K disease. As Borromeo explained the ailment, soldiers could hear the Jewish families coughing violently behind the closed doors of the ward.

The Nazis left the hospital without ever opening the doors of the K disease ward.

To understand why, it helps to remember that there were no antibiotics during World War II. Not for the Nazis, anyway. While penicillin had been discovered, America was the only country that had figured out how to produce it in mass quantities, and it didn’t make its way to Allied forces until shortly before the landing at Normandy in 1944. Which means that, had the Nazi soldiers at Fatebenefratelli Hospital been exposed to K disease, they knew there was nothing they could take to get rid of it.

That fear kept the Nazis from opening the ward’s doors, behind which they would’ve found dozens of Jewish men, women, and children–all of them perfectly healthy.

Because K disease wasn’t real.

Rather, it was a brilliant, life-saving scheme dreamed up by Borromeo and Father Maurizio, the Catholic priest who oversaw the hospital. After the Nazis occupied Rome in 1943 and began rounding up the city’s Jewish residents, the two men decided that every Jewish person who came to the hospital seeking refuge would be admitted for treatment of K disease, which was a subtle reference to Albert Kesselring, the Nazi field marshall who oversaw German operations in the Mediterranean. If Nazis asked about Jewish patients allegedly hiding in the hospital–as they eventually did–Borromeo could present intake records showing that the Jews in his care were all dangerously ill.

If Nazis asked about Jewish patients allegedly hiding in the hospital Borromeo could present intake records showing that the Jews in his care were all dangerously ill.

Borromeo left no English-language record of his reasoning, but his K disease strategy took brilliant advantage of Nazi propaganda, which alleged that Jews in Germany, Poland, and elsewhere carried more diseases than other populations. That vicious stereotype, combined with memories of Germany’s crippling experience with typhus during World War I, had primed Nazis soldiers to be more fearful of sick civilians than Allied troops.

Borromeo’s imagination and courage saved dozens of families in Rome. But he wasn’t the only European doctor who used his medical knowledge to save Jewish families from Nazi persecution. Eugene Lazowski, a doctor in Poland, managed to save as many as 8,000 Jews by creating a fake typhus epidemic.