Concerned about the rise of facial-recognition technology, some designers are creating fashion for a somewhat counterintuitive purpose: not to get noticed, at least by the cameras.

In the Netherlands, Jip van Leeuwenstein designed a transparent “surveillance exclusion” mask that obfuscates a wearer’s face to facial-recognition cameras but not other people.

“By wearing this mask formed like a lens it possible to become unrecognizable for facial recognition software and because of it’s transparence you will not lose your identity and facial expressions,” von Leeuwenstein writes. “So it’s still possible to interact with the people around you.”

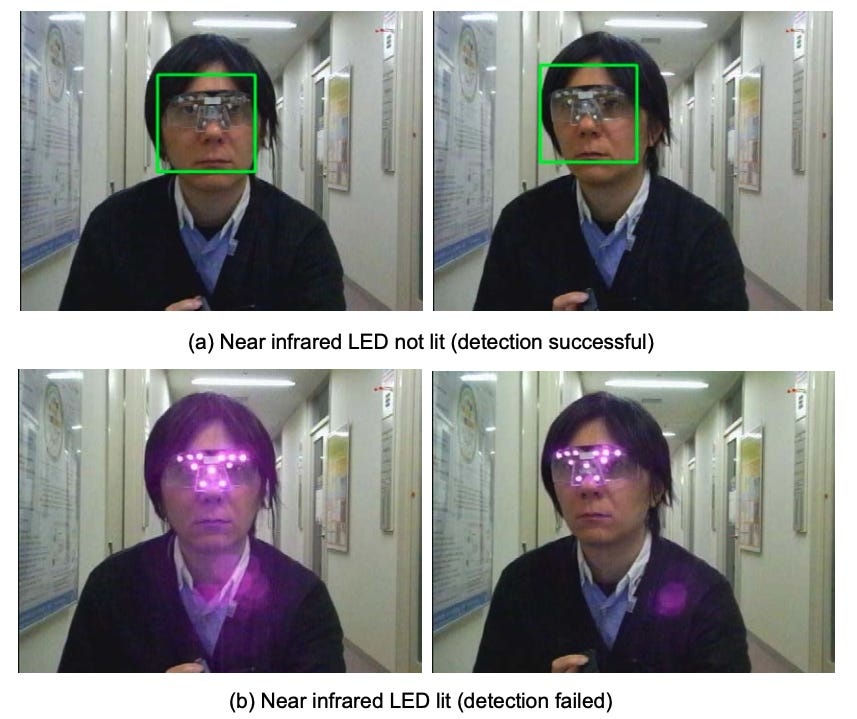

In Japan, Isao Echizen, a professor at the National Institute of Informatics in Tokyo, designed a “privacy visor” fitted with near-infrared LED lights. When worn, the facial-recognition software can’t tell there’s a human face behind the lights, according to Echizen’s tests.

In the U.K., artists in “The Dazzle Club” have walked the streets London with their faces painted in blue, red and black stripes in an effort obfuscate their faces from the city’s 420,000 CCTV cameras, only some of which are using facial-recognition technology.

“There has always been something subversive about streetwear, and one of the new areas of subversion is definitely surveillance and, in particular, facial recognition,” Henry Navarro Delgado, an art and fashion professor at Canada’s Ryerson University, told Reuters.

In September, a British court ruled that government use of facial-recognition technology doesn’t violate privacy and human rights.

Other anti-surveillance apparel includes shiny fabrics that reflect thermal radiation that drones search for, beanie hats that confuse the facial-recognition system ArcFace, and Hyperface, which makes clothing with patterns that confuse A.I. into focusing on the fabric rather than your face.

“The main significance is creating awareness,” Delgado told Slate. “That’s why fashion is so effective: You have something to say, you wear it, people see you, it’s immediate. Part of the purpose is to make people who normally don’t think about this aware that these technologies are out there, and we’re being watched.”

Facial recognition in the U.S.

Surveillance cameras are common on city streets in the U.S. city, but most cameras aren’t equipped with facial-recognition technology, as millions are in China and, to a lesser extent, the U.K. In May, San Francisco became the first U.S. city to ban facial technology on city property, not including airports.

“Good policing does not mean living in a police state,” said city councillor Aaron Peskin. “Living in a safe and secure community does not mean living in a surveillance state.”

But such comparisons are silly, according to Daniel Castro of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation.

“In reality, San Francisco is more at risk of becoming Cuba than China — a ban on facial recognition will make it frozen in time with outdated technology,” he said, adding that governments “can use facial recognition to efficiently and effectively identify suspects, find missing children or lost seniors, and secure access to government buildings.”

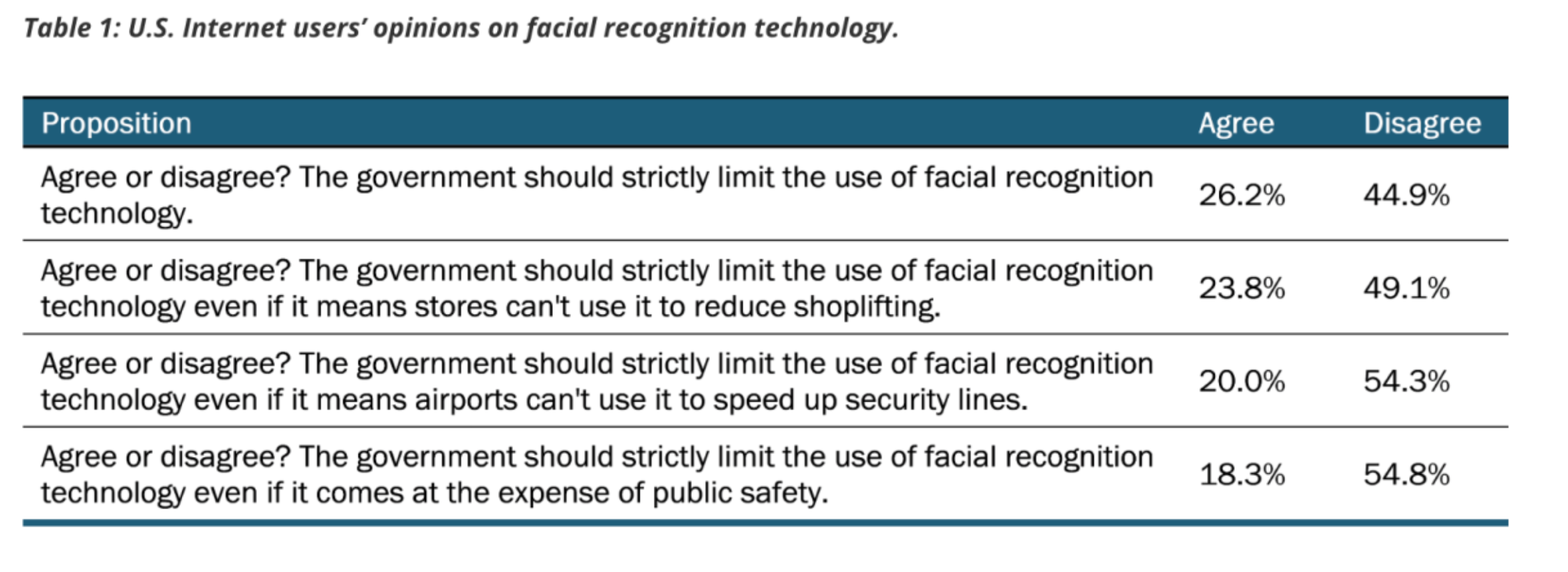

The results from a recent datainnovation.org survey suggest that most Americans would agree with Castro.

The surveyors wrote:

“There were some differences in these opinions based on age, with older Americans more likely to oppose government limits on the technology. For example, 52 percent of 18 to 34-year-olds opposed limitations that come at the expense of public safety, compared to 61 percent of respondents ages 55 and older. In addition, women were less likely to support limits than men. For example, only 14 percent of women support strictly limiting facial recognition if it comes at the expense of public safety, versus 23 percent of men.”

This article was reprinted with permission of Big Think, where it was originally published.