Most vaccinations need to be kept refrigerated: they’re at their most stable between 35 to 47 degrees (that’s right, we’re talking restaurant ServSafe rules!).

Obviously, this complicates getting these life-saving shots to where they need to be, since they also must be refrigerated along the way. (This is especially problematic in poor countries with hot climates.)

But researchers at Michigan Tech and the University of Massachusetts Amherst have developed a new form of vaccine preservation, and it sounds pretty adorable:

“Virus burritos.”

One Virus Burrito, Hold the Guac

“You wouldn’t take a steak and leave it out on your counter for any length of time and then eat it,” Caryn Heldt, director of Michigan Tech’s Health Research Institute, said in a press release.

“A steak has the same stability issues (as a virus) — it has proteins, fats, and other molecules that, in order to keep them stable, we need to keep them cold.”

That stability is key to vaccine preservation. The WHO estimates that up to 50% of vaccines are wasted every year, much of that due to “lack of temperature control and the logistics to support an unbroken cold-chain.”

In other words: we can’t keep the damn things cold.

The solution, proposed by Heldt and UMass Amherst professor Sarah Perry in Biomaterials Science, is to harness the power of compression — not cold — to preserve viral vaccines.

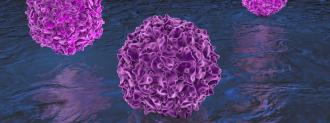

Viruses fall apart when they get warmed up — or when there’s space for them to laze about. Inside your body, viruses get squished, which helps them hold together even in a warmer environment.

Heldt and Perry’s idea was to recreate that squishing, like giving the vaccines a thunder blanket. Or a burrito wrapper.

They did this by using synthetic proteins, called polypeptides, which stick together to form a liquid.

That liquid wraps the viruses up all snug, creating little virus burritos. Held together by their liquid tortilla, they can maintain their stability without having to be kept cold.

“The great thing about these amino acids is that they are the same building blocks as in our bodies,” Heldt said. “We’re not adding anything to the vaccines that aren’t already known to be safe.”

The Limitations

There’s a catch, though: you can only wrap up the little burritos if the viruses don’t already have an envelope, a fatty shell of protection, around them. Still, there’s some mean characters capable of being Chipotle’d, including polio and hepatitis A.

Finding out how to use the burrito technique when the virus involved has an envelope — like SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19 — is the next step.

“Crowding alone isn’t a universal strategy to improve virus stability,” Perry says. “We need to understand how different polymers interact with our viruses and how we can use this to create a toolbox that can be applied to future challenges.”