The U.K. has seen a surge in COVID-19 cases this fall — and a new coronavirus mutation appears to be responsible for many of them.

“It seems that the spread is now being driven by the new variant,” Prime Minister Boris Johnson said during a press conference. “It does appear that it is passed on significantly more easily.”

More than 40 nations are now restricting travel to the U.K., but the coronavirus mutation has already been detected in other nations, meaning those restrictions are unlikely to stop its spread across the globe.

But it isn’t clear yet whether this new variant is just riding a wave of new infections, or whether it is actually causing the virus to spread faster.

Here’s what we know about the mutations so far — and what we still need to figure out.

What Is a Coronavirus Mutation?

The fact that the coronavirus is “mutating” might sound alarming, but mutating isn’t anything unusual for a virus.

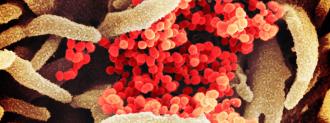

As it spreads, a virus’s genetic code will occasionally undergo slight changes — these changes are mutations. When we find a virus with a unique set of mutations, we call it a new strain.

Scientists have been keeping tabs on coronavirus mutations throughout the pandemic, and typically, they find one or two new mutations every month in infected people.

Where Is the New Coronavirus Strain?

Researchers first discovered this strain in the U.K. in September. Since then, it’s been found in Denmark, Italy, Australia, Gibraltar, and the Netherlands.

Many nations haven’t sequenced the coronavirus strains infecting their populations, though, so it could be elsewhere, too.

What’s Special about This Strain?

The main thing that stands out about the coronavirus mutation spreading in the U.K. is how often we’re now seeing it. In November, it was behind about 28% of COVID-19 cases in London. Three weeks later, it had jumped to 62%.

This could be due to chance — the strain may have just happened to be at the center of one or more superspreader events.

Evidence suggests the strain evolved inside a single person during a very long infection.

However, while it doesn’t contain any mutations scientists haven’t seen before, this strain does contain a unique combination of more than a dozen mutations related to the coronavirus’s ability to spread.

One of the mutations, for example, helps the coronavirus’s spike protein bind better to human cells, while another helps the virus dodge our immune system.

That suggests that this coronavirus mutation might be a result of evolutionary adaptation and not random chance.

The unusually large number of mutations, appearing all at once, suggests that the virus evolved inside a single person during a very long infection, scientists say.

Is This Strain More Deadly?

While this strain appears to spread more easily than others, at least in Petri dish studies, there’s no indication that it’s more deadly.

“It seems like this new strain is more contagious,” former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb told CBS’ Face the Nation. “It doesn’t seem to be any more virulent, any more dangerous than run-of-the-mill COVID.”

While COVID-19 reinfection is possible, there’s also nothing to suggest that people who’ve already recovered from the disease will be particularly susceptible to this strain.

Will COVID-19 Vaccines Still Work?

Experts say there’s no evidence that coronavirus vaccines are any less effective against this strain than others.

However, the U.K. just started distributing Pfizer’s vaccine on December 8. No one has received the second dose yet.

The take-home message for right now is that we need to get more information.

Krutika Kuppalli

In other words, no one in the U.K. is fully vaccinated against COVID-19 yet, and until a significant portion of the population is, we won’t know for sure how our vaccines hold up against this coronavirus mutation.

However, even if the vaccines turn out to be less effective against this coronavirus strain, that doesn’t mean we need to start the development process back at square one — we could adjust the shots to account for the mutations.

“You can imagine a process like exists for the flu vaccine, where you’re swapping in these variants and everyone’s getting their yearly COVID shot,” evolutionary biologist Trevor Bedford told the New York Times. “I think that’s what generally will be necessary.”

What’s Next?

The important thing now is learning everything we can about this new coronavirus mutation, so researchers across the globe are studying it to see whether it’s really more contagious than other strains.

They’re also testing whether antibodies in the blood plasma of coronavirus survivors and vaccinated people can prevent this strain from infecting cells — that should help us figure out whether our vaccines are going to need to be tweaked in response to it.

“The take-home message for right now is that we need to get more information,” infectious diseases specialist Krutika Kuppalli told the Washington Post. “In the meantime, we all need to really double down on our public health measures — wearing masks, remaining physically distanced, avoiding crowds of people.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].