Based on just three particles of dust, Australian researchers have determined that a near-Earth asteroid is 4.2 billion years old — and practically indestructible.

The knowledge gap: Asteroids can broadly be divided into two types: monolithic (one big rock) or rubble pile (many rocks held together by gravity).

Past research has given astronomers a pretty good idea of how durable monolithic asteroids are — a 500-meter-wide one would likely survive only several hundred thousand years in our solar system’s asteroid belt due to collisions with other asteroids — but the durability of rubble pile asteroids has remained unknown.

To stop an impending impact, we need to better understand how well rubble pile asteroids can withstand damage.

Why it matters: Our solar system contains millions of asteroids, and while most will never come close to Earth, an impact from a large space rock could flatten a city or worse.

Luckily, if a large asteroid was on a collision course with our planet, we may know about it well in advance, potentially giving us time to take defensive action — but to know what action to take, we need to better understand how well rubble pile asteroids can withstand damage.

“That result was totally unexpected … Itokawa has survived almost an order of magnitude longer than its monolith counterparts.”

Fred Jourdan and Nick Timms

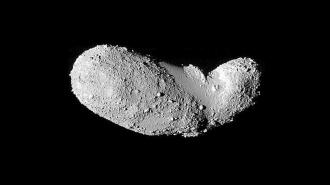

What’s new? A Curtin University-led research team has now analyzed three dust particles from Itokawa, a 500-meter-wide rubble pile asteroid that JAXA’s Hayabusa probe returned samples from in 2010.

Based on that analysis, they believe that the rubble pile asteroid formed from the fragments of an ancient collision, when a meteor hit its monolithic parent at least 4.2 billion years ago.

“That result was totally unexpected,” lead author Fred Jourdan and co-author Nick Timms wrote in the Conversation. “It also means Itokawa has survived almost an order of magnitude longer than its monolith counterparts.”

How it works: The team’s conclusion was based on two analysis techniques.

One of them, “electron backscattered diffraction,” involved firing an electron beam at the dust and then detecting the electrons that scattered back. This revealed the structure of the particles, and allowed the researchers to determine they had been shocked by an impact in the past.

For the other technique (argon-argon dating), the team used a laser beam to measure radioactive decay in the particles — that allowed them to determine the date of the impact.

“Constant collisions will simply crush the gaps between the rocks.”

Fred Jourdan and Nick Timms

But how? Past modeling has suggested that Itokawa is 40% porous, and the Curtin team says this porosity is how the asteroid has managed to survive so long.

“[C]onstant collisions will simply crush the gaps between the rocks, instead of breaking apart the rocks themselves,” wrote Jourdan and Timms. “So, Itokawa is like a giant space cushion.”

Looking ahead: Based on their discovery that Itokawa is nearly as old as the solar system itself, the researchers posit that there might be more rubble pile asteroids in our corner of the universe than we anticipated — after all, once they form, they’re all but impossible to destroy.

They aren’t impossible to deflect, though.

“We may need to use the shockwave of a nuclear blast in space.”

Fred Jourdan and Nick Timms

NASA’s DART mission proved we can slightly redirect a small rubble pile asteroid by slamming a spacecraft into it. Given enough time, a small change in direction can compound, slowly steering an incoming asteroid away from danger. But if an asteroid is already close to Earth, a small change might not be enough.

Jourdan and Timms have an alternative idea.

“We may need to use the shockwave of a nuclear blast in space, since large explosions would be able to transfer much more kinetic energy to a naturally cushioned rubble pile asteroid, and thus nudge it away,” they wrote.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].