In their ongoing hunt for extraterrestrial life, astronomers are searching for three key ingredients: liquid water, a source of energy, and complex organic molecules, which make up the basic building blocks of life as we know it.

If a planet has all three, it’s considered a more promising location for life to emerge — but it’s not as easy to discover as it sounds.

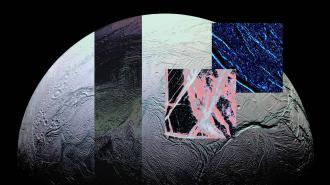

Evidence for life? Tantalizingly, all three of these ingredients may exist on some of the moons of Jupiter and Saturn, which host vast oceans of liquid water below crusts of ice kilometers thick.

As they orbit their host planets, both Europa (Jupiter’s 4th largest moon) and Enceladus (Saturn’s 6th largest) are stretched and squeezed by tidal forces, a source of energy which helps heat their subsurface oceans to far more comfortable temperatures than their frigid exteriors would suggest.

The Cassini measurements were not enough to pin down the origin or identity of the molecules.

That leaves just the third key ingredient. That one is ultimately far more difficult to detect from Earth, yet across several missions to Jupiter and Saturn over the past few decades, astronomers have now gathered enticing evidence that complex organics may be abundant on both Europa and Enceladus.

In 2015, NASA’s Cassini probe passed directly through an icy plume that had erupted from a crack on Enceladus’ south pole. With its in-built Cosmic Dust Analyser, the probe identified the signature of complex organic molecules in the ice grains. However, the measurements were not enough to pin down the origin or identity of the molecules.

The challenge: As ice grains in the plume were ejected into space at speeds of over 400 meters per second, they would have impacted Cassini’s detector at colossal speeds.

According to some astronomers, these impacts may have been violent enough to break apart any organic molecules riding along inside the grains, degrading any samples picked up by the probe. Yet due to the limited resolution of Cassini’s measurements, we can’t be sure whether or not this really happened.

Ultimately, without a clear understanding of what happens to complex organics during these detector impacts — be it with Cassini, or any future missions to Europa or Enceladus — astronomers can’t make any particularly reliable predictions about the life-harbouring potential of these icy moons.

Future missions could study the icy plumes without damaging any complex organic molecules in the process.

The experiment: In a new study published in PNAS, Robert Continetti and a team of astronomers at UC San Diego have shed new light on the problem. They wanted to imitate the impacts taking place as Cassini passed through Enceladus’ icy plume, combined with measurements from a state-of-the-art mass spectrometer.

The researchers started by preparing a water-based solution of various amino acids — those are the molecular building blocks of proteins, which are essential to all life on Earth. Through a technique named “electrospray ionization,” they then pushed the solution through a thin capillary tube while subjecting it to a high voltage.

In the process, the liquid became charged, creating a fine spray of charged droplets just a few hundred nanometres across as it emerged from the end of the tube. Continetti’s team then injected the droplets into a vacuum, where they immediately froze into tiny, solid ice grains, much like those picked up by Cassini.

From here, the grains were accelerated by strong electric fields and then passed into a custom-built instrument named the Hypervelocity Ice Grain Impact Mass Spectrometer. Crucially, this device could select grains with specific ratios between their mass and charge — a value determined by their amino acid contents — to impact an ion detector at the back of the instrument.

Withstanding impacts: Remarkably, the team found that each type of amino acid they studied survived the impact, even when the grains were accelerated to speeds of over 4 kilometers per second, which is much faster than the speeds of the ice grains picked up by Cassini.

Their results were consistent with Cassini’s data and also showed that the amino acids became less detectable when prepared in salty solutions. Since Enceladus’ ocean is likely very salty, this result goes further to explaining the probe’s observations.

Altogether, the results provide the first unambiguous evidence that, using similar instruments, future missions could safely fly through the icy plumes of Europa and Enceladus and study them without damaging any complex organic molecules in the process.

Continetti’s team now hopes their results could offer important guidance for future missions to the icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn — including NASA’s Europa Clipper Mission, due for launch in October this year. In turn, they may even bring us a step closer to knowing whether life may yet exist on other worlds in our solar system.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].