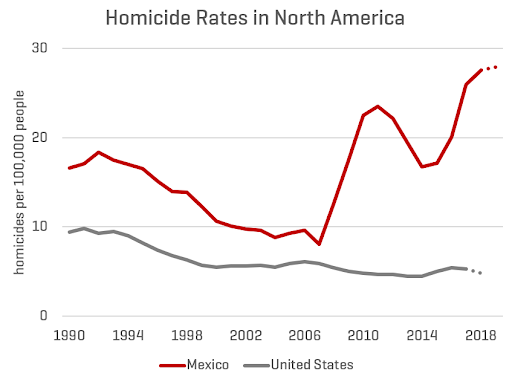

In 2007, Mexico was catching up to its northern neighbor — at least when it came to safety. Two decades of rapidly declining violence had brought the country’s murder rate to within throwing distance of the United States.

INEGI and SNSP, compiled by Mexico Crime Report.

Then, quite suddenly, a war broke out. Murders more than tripled, from fewer than 9,000 in 2007 to over 27,000 in 2011. In 2018, murder hit another all-time high, with over 34,000 homicides.

This year, murder has continued to climb, with June being one of the bloodiest months since the Mexican Revolution. So far, Mexico is on course for 40,000 homicides in 2019 — more than twice as many people as died in the Syrian civil war last year.

The cause of the violence is obvious: a massive war between Mexico’s cartels. But the dynamics that are fueling violence south of the U.S. border are not unique to Mexico, or even to its sophisticated, transnational drug cartels. The problem of organized criminal violence afflicts nearly every country in the Americas.

In Central America, gangs like MS-13 and Barrio 18 have fostered an epidemic of murder, extortion, and kidnapping, which is helping drive the surge of migrants seeking asylum at the U.S. border.

In the United States, battles between street gangs have recently caused murder to spike in cities like Chicago, Baltimore, and St. Louis, while notorious prison gangs, like the Mexican Mafia, Aryan Brotherhood, and Latin Kings, are effectively running the U.S. prison system. In South America, a war between rival gangs has pushed Brazil’s murder rate to all-time highs.

The natural response for governments facing such violent groups is total suppression: a full-frontal assault to crush the organizations and lock up the ringleaders.

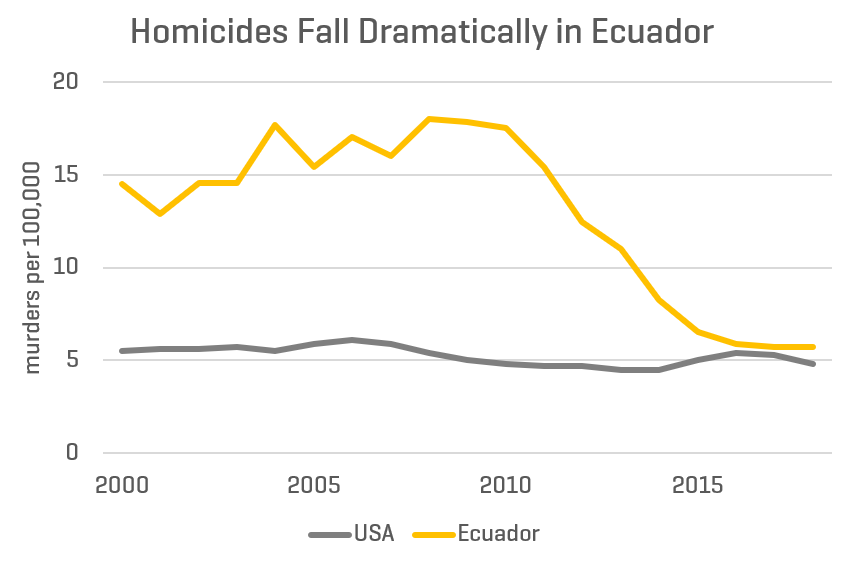

But there is a powerful argument that this strategy, while understandable, is actually responsible for making the violence worse. One country is trying a radically different approach: in 2007, Ecuador began a process of “legalizing” its street gangs, and its murder rate has fallen by 70% in the decade since.

It’s easy to read too much into one anecdote from a single country, but seen in context, Ecuador’s example may offer a positive contrast to the cautionary tales seen elsewhere in the hemisphere.

Mexico: Splintering Gangs, Spiraling Violence

Mexico dealt with the violence and corruption associated with drug cartels for decades. But in 2000, a major shift occurred in the country’s power structure, when Mexico’s Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) lost its 70-year stranglehold on Mexican politics.

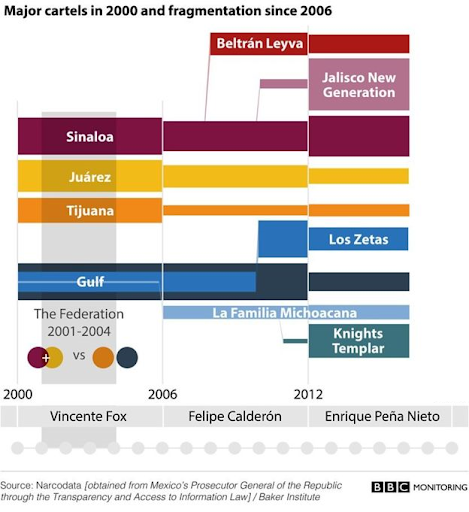

Newly elected leaders from the conservative PAN party did not directly attack the cartels, but the power transition led to turnover among police, prosecutors, and military officials. With government loyalties shifting for the first time in decades, cartels began losing their corrupt protection arrangements with the government, destabilizing the relatively peaceful relationships of previous decades. Even while the murder rate continued to fall, cartel-associated killings grew from about 1,000 a year in 2003 to nearly 3,000 in 2007.

In 2007, newly inaugurated PAN President Felipe Calderon promised to crack down on the rising violence and crush the cartels. For the first time in its drug war, Mexico deployed tens of thousands of troops inside the country. The military was tasked with executing Calderon’s “kingpin” or “decapitation” strategy, systematically killing or capturing cartel leadership to try to destabilize the groups.

Officially, this strategy is still working. Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, leader of the Sinaloa Cartel, was just convicted and is now facing life in an American prison, after being recaptured in 2016. The leader of the Zetas Cartel was also captured last year. Dozens of other shot-callers have been killed or imprisoned in recent years.

But rather than eliminating the cartels, this policy has simply caused them to splinter and fragment into new groups. There are now more cartels than ever, waging a bloody, multi-sided war for territory across the country. Research from the University of San Diego has tied the recapture of El Chapo, in particular, to the latest surge in violence, as gangsters fight for control of the Sinaloa Cartel and its territory.

Credit: BBC

Former President Enrique Pena Nieto, who served from 2013-2018, declared last year that the military had “won” the war against the big cartels, but admitted that “this weakening brought with it small criminal groups, without there being the capacity on the local level to effectively confront them.”

In cities like Acapulco, the LA Times reports, “the cartel system has collapsed completely, with historic levels of violence being driven by dozens of warring street gangs.”

The churn among senior management (and the loss of reliable partners inside the state) has caused organized crime to become disorganized — but it hasn’t disappeared, and the chaos has made the violence worse than ever. With more gangs fighting over the same turf, there are exponentially more opportunities for conflict, and local police are hopelessly overwhelmed.

Supply and Demand for Gangs

The theory behind suppression strategies is that the gang itself is the problem. If we get rid of the organization — capture its leaders, disrupt recruitment, seize assets, etc. — it will crumble and evaporate, because it won’t be able to sustain itself. Problem solved.

But that’s almost never what actually happens. In Chicago, police tried a similar zero-tolerance approach and “decapitated” the old gangs, and the result was the same as in Mexico: smaller, less organized, and more numerous gangs, fighting a dizzyingly complex war. Chicago’s violence has been difficult to quell precisely because there is nobody to call a ceasefire — or rather, there are now too many people who have to negotiate and agree on it.

Brown University economist David Skarbek isn’t surprised by the failure of suppression strategies, because they are based on the same kind of mistake that has been playing out in the U.S. prison system for decades. In his book The Social Order of the Underworld: How Prison Gangs Govern the American Penal System, he argues that we have been systematically misdiagnosing why gangs exist — and so it’s no wonder why our solutions keep failing.

“Gangs don’t exist because there are just a lot of particularly evil people, or because there are sort of ‘gang member’ types, people who are inclined to be gang members,” he says. Instead, paradoxically, “Gangs exist because people want more safety in a dangerous, volatile environment — and they want more regular access to contraband in illicit markets.”

In other words, gangs aren’t a “supply-side” problem — it’s not about the group itself, it’s about the social and economic dynamics that create the demand for gangs in the first place. In violent, risky situations (like overcrowded prisons), people form gangs because they need things that the authorities cannot give them (like guaranteed safety) or will not (like cell phones and illegal drugs).

To facilitate these services, gangs have also created rules to regulate the black market and resolve disputes in private. “The gangs have some pretty clear rules about when you can use violence against other prisoners. You can’t just choose to assault another prisoner,” Skarbek says.

In violent, risky situations, people form gangs because they need things that the authorities cannot give them.

“They’ll organize a controlled setting— maybe in a cell at a time when correctional officers aren’t going to be around. They’ll allow interpersonal violence to take place, but they’ll regulate it in a way so that it’s less likely to destabilize the prisoner community.”

Spontaneous, public acts of violence often lead to prison-wide lockdowns, and that interferes with the gangs’ business. “They can’t sell drugs or turn a profit during periods of lockdown. They have a private financial incentive to reduce large scale disruptions, large scale rioting, and so that gives them the incentive to want to govern these interactions.”

“I think of (gangs) as the symptom of a disease, rather than the underlying disease itself. The underlying disease is forcing people into dangerous situations where there’s insufficient resources or governance.”

Skarbek has no illusions about the brutality that these gangs are willing to inflict, both inside and out of prison. “There’s much to be worried about with gangs,” he says. “But I think of them as the symptom of a disease, rather than the underlying disease itself. The underlying disease is forcing people into dangerous situations where there’s insufficient resources or governance.”

Abuela Needs a Sicario

In his book Narconomics: How to Run a Drug Cartel, the journalist Tom Wainwright tells the story of Rosa, “a barrel-shaped seventy-year-old who cannot be taller than about four feet six,” who works as a maid in a suburb of Mexico City.

“In between mopping floors and making blueberry pancakes,” Wainwright recounts, “she is plotting a murder.”

Rosa had a problem that is increasingly common throughout Mexico: a pair of men had for years been killing, robbing, and stealing from her community with absolute impunity.

Three months ago, one of her sixteen grandchildren came home with her husband to find two burglars in the middle of ransacking their house. The robbers escaped but later came back to give the husband a vicious beating with an axe handle, as a warning not to report them. “He still walks like this,” Rosa says, mimicking the awkward swing of his fractured arms.

… The police are doing nothing about all this. “Honestly, I don’t trust them,” Rosa says. “If the authorities don’t do anything, what are we left with? One can’t live like this anymore. We can’t live with the fear that at any moment they can enter our house and kill us.”

So Rosa and her neighbors began raising money to hire a hitman (sicario) to take out the robbers. “Rosa’s story may be horrifying, but it is not as unusual as it sounds,” according to Wainwright. “Many organized criminal groups provide this sort of ‘protection.’”

Drug dealers, for instance, cannot go to the police if they are robbed.

This desperate grandmother was hardly a hardened criminal, but her case illustrates exactly the kind of incentives faced by people who find themselves in dangerous, poor, violent situations — within a prison, neighborhood, or even a country — where the formal authorities cannot or will not provide security.

Drug dealers, for instance, cannot go to the police if they are robbed, cheated, or attacked, and so they tend to band together to defend themselves and their market — and they aren’t as patient as your average abuela.

Now, after years of rising insecurity, corruption, and chaos, ordinary citizens are also succumbing to the logic of gangs and forming armed groups for protection. In the Mexican state of Guerro, for example, private “self-defense groups” (effectively, vigilante gangs) have banded together into a 11,000-member paramilitary to defend their towns and fight the cartels.

But this third power structure, outside both the government and the cartels, risks pouring new fuel on the conflict and further undermining the state — and, as Colombia has shown, paramilitaries are no more accountable or less susceptible to corruption than other groups.

A Different Path

Ultimately, the way to defeat gangs is to eliminate the demand for them by providing reliable security inside prisons, schools, and the community at large. This isn’t easy to do, and the specifics will differ depending on the place and purpose of the gang.

Unfortunately for Mexico, there is little sign that newly inaugurated President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (also known as AMLO) is changing course. In July, he inaugurated a new 70,000-strong militarized “National Guard” to try to quell cartel violence and circumvent corruption in the army and police. The new force may provide a brief boost to security, but it won’t fundamentally change the dynamics that have corrupted the local police, federales, and army before it.

Instead of hoping for a miraculous breakthrough from brute force, governments should look for ways to mitigate the worst aspects of gangs. In his wide-ranging study Making Peace in Drug Wars: Crackdowns and Cartels in Latin America, the political scientist Benjamin Lessing argues that American governments need to abandon their tough-on-crime, maximum pressure strategy toward gangs and embrace a “conditional repression” strategy.

Conditional repression means offering a deal to the gangs (whether explicitly or implicitly): “We have a ton of firepower, but on a normal day, we’re not going to let it all loose on you — unless you do X, Y, or Z”— for example, killing civilians, children, or police, or having shootouts in public.

Instead of hoping for a miraculous breakthrough from brute force, governments should look for ways to mitigate the worst aspects of gangs.

Lessing argues that “brute-force repression generates incentives for cartels to fight back, while policies that condition repression on cartel violence can effectively deter cartel-state conflict.”

The downside of this approach is that it tacitly admits that we are not “doing everything we can” to stop organized crime. The upside is that, because police pressure is not always 100% maxed out, there is a significant deterrent available to discourage open violence and channel cartel operations into less destructive paths.

Conditional repression tells cartel leaders that, at any given time, the police have the power to make their life much worse than it is. Maximum repression tells the cartels they have nothing to lose by attacking the state.

There is evidence from across Latin America that the government can also use this privileged position to negotiate and enforce truces between rival cartels, creating an incentive for the cartels to stop fighting each other. In 2012, the government of El Salvador (assisted by the Catholic Church) negotiated a truce between MS-13 and Barrio 18, which cut the country’s murder rate in half in a single year.

Unfortunately, that truce fell apart two years later when the government minister responsible for it was removed from office. Brazil’s recent surge in murder has been blamed on a gang truce from 1997 suddenly falling apart in the middle of 2016, as violence spilled from the country’s dangerously overcrowded prisons into the streets.

“Brute-force repression generates incentives for cartels to fight back, while policies that condition repression on cartel violence can effectively deter cartel-state conflict.”

In Ecuador, the government seems to have embarked on a more successful and durable strategy of conditional repression, and the result has been a massive reduction in violence. By 2018, the homicide rate in Ecuador was nearly as low as in the United States.

Sources: FBI, UNODC, media reports

Starting in 2007, Ecuador made a number of radical changes to its law enforcement strategy, by doubling its spending on security and launching an ambitious program of “legalization” for the country’s street gangs, including notorious groups like the Latin Kings and STAE.

The program allows gang members to register with the state to receive benefits, including training and job placement. Members are not asked to give up their gang affiliation — to the contrary, the goal is to bring in current gang members and transform the gang into a more benign social group — but they are expected to abide by the conditions of the program.

According to a report by the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), “legalized” gang members understand the deal: “Our leaders told us that we were no longer allowed to go to war… After that, you know, the government began to give us job opportunities. So, if we began to act violently again, the government would take away what they had already begun to give us, so what we did was to reciprocate the government’s help (to ensure the relationship continued).”

The main benefits the gang received from “legalizing” was different treatment by the police. According to the report,

Before legalization, if the STAE (gang) got together to hold a meeting in a park, the police would inevitably arrive to arrest and physically abuse them. … Legalization was primarily a reinstatement of the right to the city… They are no longer stopped and frisked or targeted for wearing their gang colors in public spaces. Many noted that this was perhaps the biggest victory of legalization.

But another key aspect of the program was conditional on keeping the street gangs away from the cartels, which historically do not operate directly in Ecuador, but launder money and smuggle drugs through the country.

“This is one of the most important aspects of the Ecuadorian approach,” the report argues. “Mano dura (the heavy hand) for cartels but inclusion towards gangs. The government actively and consciously strove to avoid gangs working for cartels (especially due to the proximity of Peru and Colombia, both major drug-trafficking hubs), hence they aggressively pursued organized crime networks while applying policies of social inclusion to street gangs.”

The legalized gang members understand that the arrangement is precarious, and it could fall apart if a new president is elected. According to the IADB, their goal right now is to “institutionalize the legalization process and give it a sustainability and legitimacy that would be impervious to political shifts.”

It’s not clear how much of Ecuador’s decline in murders is due to random factors, more and better policing, or the new strategy on gangs. No one should imagine that Ecuador’s gang problem has vanished, and it would be facile to suggest that Mexico should simply import this program wholesale, applying it to criminal organizations that are very different than Ecuador’s relatively small street gangs.

But at a high level, the difference in approaches is worth noting. Ecuador’s policy admits that as long as there is a demand for gangs, they will continue to exist, and they must be dealt with, rather than blindly smashed. By contrast, Mexico seems determined to follow the supply-side, mano dura policies that have failed across the Americas.

In Making Peace in Drug Wars, Lessing argues for a pragmatic approach, managing the problem of criminal gangs without chasing the illusion of eliminating it overnight:

It is critical to reframe the policy problem, from eradicating drugs or crushing the cartels or punishing dastardly traffickers, to minimizing the harms produced by the drug trade… Reframing the problem ultimately implies “diplomatic recognition”: accepting that as long as there is demand for drugs, there will be traffickers, and orienting repressive policy to favor the sorts of traffickers we would like to have.

That is a hard sell, especially for voters that are justly horrified and outraged by the crimes these groups have perpetrated. What Ecuador might ultimately show us is that it is possible for a democratic government to increase basic public safety, while incentivizing less bad behavior from its gangs. The results have been a rare positive example in one of the most violent regions of the world. Whether the rest of the region can learn from its example remains to be seen.