Cornell University researchers have resurrected an ancient version of the enzyme Rubisco in the hope of supercharging photosynthesis in today’s plants — helping us grow more food in the face of climate change and a growing population.

The challenge: The increasing amount of carbon dioxide we’re pumping into the atmosphere is making our climate hotter and drier. If the plants we rely on for food don’t adapt well to those conditions, we could find ourselves struggling to feed the growing world population.

“Even under optimistic climate change scenarios, where societies enact ambitious efforts to limit global temperature rise, global agriculture is facing a new climate reality,” said Jonas Jägermeyr, a crop modeler and climate scientist at NASA.

In other words, we will have to adapt.

A better Rubisco: Plants convert CO2, light, and water into food through photosynthesis. By making photosynthesis more efficient, we could supercharge plants’ growing power, resulting in more food from the same land.

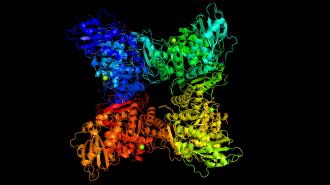

One possible way to do that is by making the Rubisco enzyme better at its job.

“Global agriculture is facing a new climate reality.”

Jonas Jägermeyr

This enzyme is responsible for pulling CO2 from the atmosphere and into the plant, and it’s mind-bogglingly inefficient at the process, working slowly and often mistakenly grabbing oxygen molecules in addition to CO2.

As UCLA biochemist Sabeeha Merchant put it in 2017, “If you designed [Rubisco], it would be considered an engineering failure.”

Ancient enzymes: To build a better Rubisco, the Cornell team looked to the past, sequencing Rubisco genes from many of today’s plants to create an evolutionary tree of the enzyme. This allowed them to predict what Rubisco enzymes looked like 20-30 million years ago.

Today’s Rubisco enzymes are mind-bogglingly inefficient at pulling atmospheric CO2 into plants.

During that time period, CO2 levels in the atmosphere were about 500-800 parts per million (ppm). Today, we’re at about 420 ppm, but for hundreds of thousands of years, prior to the 20th century, levels were about 300 ppm.

That means today’s plants contain Rubisco enzymes that have evolved to work in an environment with far less CO2 than the one they’re actually living in. In theory, reverse engineering the ancient version of the enzyme, which evolved in much higher CO2 concentrations, could speed up photosynthesis.

The next step in the team’s study seems to support this — when they tested the efficiency of the ancient Rubisco enzymes, they found versions that “do have superior qualities compared to current-day enzymes,” said senior author Maureen Hanson.

“We hope that by adapting Rubisco to present day conditions, we will have plants that will give greater yields.”

Maureen Hanson

Looking ahead: By tweaking today’s plants to produce the promising versions of Rubisco, the researchers hope we’ll be able to supercharge their growth.

“For the next step, we want to replace the genes for the existing Rubisco enzyme in tobacco with these ancestral sequences using CRISPR [gene-editing] technology, and then measure how it affects the production of biomass,” Hanson said.

Tobacco is a popular test plant because it is leafy like many staple crops but also grows quickly and is easy to modify.

“We certainly hope that our experiments will show that by adapting Rubisco to present day conditions, we will have plants that will give greater yields,” she continued.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].