The weight loss drug revolution appears to have truly arrived. For decades, there have been compounds available that trim weight or buff muscles, but they always have come with dangerous side effects and worsened long-term health. The trade-off simply wasn’t worth it. A prized weight loss pill still seemed far away.

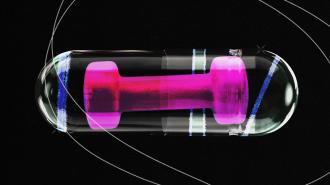

Now, drugs like Ozempic (semaglutide) and Mounjaro (tirzepatide) — backed by large, lengthy clinical trials — trigger 12% to 18% weight loss and sharply reduce the risk of death from heart disease, with minimal side effects. They’re currently available as injections, but pill forms are on the way.

These drugs help users lose weight by sharply reducing appetite, and thus caloric intake. Scientists are also on the hunt for pharmaceuticals that affect the other side of the weight loss coin: caloric expenditure. In short, they would cause the body to act like it’s exercising. One team, led by researchers at Washington University in St. Louis, is currently testing a potential candidate.

Exercise pill

Their weight loss drug, SLU-PP-332, acts on estrogen receptor-related receptors (ERRs), which are found in tissues that demand a lot of energy, like skeletal muscles, the liver, and the heart. When active, these receptors trigger metabolic changes associated with exercise, like increasing muscles’ ability to consume oxygen, boosting their breakdown of fat for energy, and revving up metabolism.

In a study published earlier this year, the research team gave healthy mice SLU-PP-332 and found that they could run 70% longer and 45% further than mice not given the drug.

In a more recent study published late last month, they tested SLU-PP-332 on mice again, this time to observe its effects on weight control and metabolism. They dosed obese mice fed a high-fat diet with the drug and gave others a placebo for four weeks. At the end of the study, mice given SLU-PP-332 weighed 12% less than their control counterparts, despite eating the same amount of food. Importantly, the weight difference all came from reduced fat mass — there was no difference in lean mass. Mice on the weight loss drug were simply using more energy, particularly from body fat. There were no severe side effects.

“This compound is basically telling skeletal muscle to make the same changes you see during endurance training,” said Thomas Burris, a professor of pharmacy at the University of Florida and the corresponding author of the study. “When you treat mice with the drug, you can see that their whole body metabolism turns to using fatty acids, which is very similar to what people use when they are fasting or exercising,” Burris added.

Cautious optimism

SLU-PP-332 has a very, very long way to go before it could join Ozempic or Mounjaro on the market. At this stage, it’s more likely to fizzle out than find success. Appropriate dosing in humans, balancing side effects and effectiveness, may prove elusive. Or maybe longer trials will reveal concerning side effects. Still, SLU-PP-332’s promising preliminary results further show how safe and effective weight loss drugs, only recently seen as a pipe dream, are set to proliferate in the ensuing decades to the benefit of millions.

This article was reprinted with permission of Big Think, where it was originally published.