In their never-ending hunt for new antibiotic compounds, researchers have turned to a tiny, slowly-ambulatory ecosystem: sloth fur.

These shambling creatures, a cultural icon of Costa Rica, are famed for their slow movement, adored for their pinched faces, and are just covered in algae and microorganisms. Yet despite these hitchhikers and their potential for disease, sloths seem to go about their molasses-like living relatively free of infection.

“If you look at the sloth’s fur, you see movement: you see moths, you see different types of insects… a very extensive habitat,” University of Costa Rica researcher Max Chavarria told AFP. “Obviously when there is co-existence of many types of organisms, there must also be systems that control them.”

In a bid to figure out just what those may be, and to see if they have clinical value, Chavarria and colleagues took samples from both two- and three-toed sloths — and within them they found bacteria capable of cranking out antibiotic compounds.

In the never-ending quest for new antibiotics, scientists are turning to a new, slowly-moving miniature ecosystem: sloth fur.

Slothworld: Sloths carry a biome on their back like a creation myth, a veritable living carpet of algae, fungi, microorganisms, and even arthropods (most notable, the delightfully named sloth moth, for whom the sloth’s droppings are an essential part of their life cycle).

While reports of cockroaches, worms, ticks, and various other creepy-crawlies have apparently been greatly exaggerated — researchers at Costa Rica’s National Institute of Biodiversity and the Sloth Sanctuary looked, putting anesthetized sloths into bags then combing stuff out of their fur — there is a thriving environment on there, with significant potential for infection.

But for some reason, sloths seem to be hale and hearty the majority of the time.

“We’ve never received a sloth that has been sick, that has a disease or has an illness,” Judy Avey, who owns a sloth sanctuary and estimates she has taken care of some 1,000 sloths, told AFP.

“We’ve received sloths that had been burned by power lines and their entire arm is just destroyed… and there’s no infection. I think maybe in the 30 years (we’ve been open), we’ve seen five animals that have come in with an infected injury. So that tells us there’s something going on in their… bodily ecosystem.”

Sloths carry a biome on their back like a creation myth, a veritable living carpet of algae, fungi, microorganisms, and even some arthropods, like the sloth moth.

Our defenses are failing: For eons, an invisible war has been raging across all life between pathogens and the hosts they infect — and humans, at least, are far from signing an armistice.

Antibiotics like penicillin have tipped the scales in favor of human health, but their overuse has caused bacteria to evolve resistance to them. Known as “superbugs,” these bacteria are considered by the WHO to be one of the top 10 global health threats facing humanity, and 1.2 million people are already dying from them every year — more than AIDS or malaria.

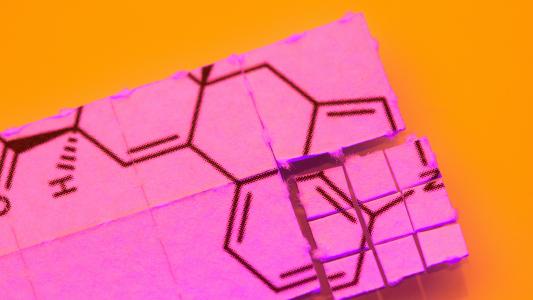

Researchers are racing for new ways to fight back. This includes hunting for bacteria-killing viruses, sifting through complex compounds (like cannabinoids), and looking into micro-mechanical weapons, including minuscule drills and nanobots to rip them apart.

But new classes of antibiotics, often discovered in exotic sources like dragons, remain one of our best bets of beating the superbugs in the future.

The researchers found nine different strains of bacteria in sloth fur samples that can produce antibiotic compounds — potential new candidates for superbug stopping.

Sloth saviors? The researcher’s sloth fur findings — published in Environmental Microbiology — included a number of potential new antibiotic sources.

Nine different strains of Brevibacterium and Rothia bacteria were found that can produce compounds that helped prevent the growth of pathogens that can infect mammals. These compounds make it possible “to control the proliferation of potentially pathogenic bacteria,” the researchers wrote.

Unfortunately, just because you find something that can kill or weaken bacteria doesn’t mean you’ve got yourself a new antibiotic ready to save lives; many a killer candidate has never made it to clinical trials, much less approved use.

A long path awaits any potential antibiotic, Chavarria told AFP.

But scouring sloth fur and other natural sources “can contribute to finding… new molecules that can, in the medium or long term, be used in this battle against antibiotic resistance,” Chavarria said.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].