A new, one-dose medication for sleeping sickness was 95% effective at eliminating the parasite in a new phase 2/3 clinical study, led by Switzerland’s Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi), with partners in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Guinea.

The drug, called acoziborole, would represent a vast improvement over current and previous therapies, which range from time-consuming at best to lethally toxic at worst — and always require painful and invasive procedures.

“Sleeping sickness is a nightmare disease that affects patients in some of the most remote settings in West and Central Africa, where distance from hospital can be measured in days,” Victor Kande, of the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Ministry of Health, said in a release.

“We are now on the cusp of a potential treatment that can be given in one day, in a single dose of three pills – this would be a revolution for doctors and communities.”

A new, one-dose medication for sleeping sickness was 95% effective at eliminating the parasite in a new phase 2/3 clinical study.

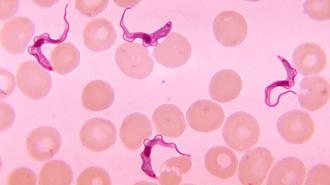

What is sleeping sickness? Caused by a parasite spread via the bite of the infamous tsetse fly, sleeping sickness — or “Human African trypanosomiasis” (HAT) — comes in two different forms, depending on which subspecies of the parasite is behind the infection.

According to the WHO, one of those subspecies, Trypanosoma brucei gambiense, is responsible for over 95% of cases.

This parasite, which resembles a living lick of flame, can lie in wait for months or even years, showing no outward symptoms before coming on with fever, headaches, joint pain, swollen lymph nodes — nothing that would set off alarm bells.

But as the parasite progresses, it eventually gets into the central nervous system, wreaking havoc on sleep schedules, causing hallucinations, confusion, mania, seizures, tremors, sensory issues, and other brutalities.

Sleeping sickness, left untreated, is lethal.

And not too long ago, said treatment could be lethal as well.

“Sleeping sickness is a nightmare disease that affects patients in some of the most remote settings in West and Central Africa, where distance from hospital can be measured in days.”

Victor Kande

“The widely available treatment then was an arsenic-based drug, and it was toxic,” DNDi clinical project leader and medical manager Wilfried Mutombo Kalonji told NPR about treating sleeping sickness in the early 2000s.

“It [the drug] could kill up to 5% of patients. I lost two of my patients. They were young, and that was a very bad experience.” The best non-toxic drug, eflornithine, requires over 50 intravenous treatments, with painful lumbar punctures needed to assess efficacy, as NPR noted.

DNDi’s previous work with French pharma multinational Sanofi, the sleeping sickness programs of DRC and Guinea, the WHO, and Médecins Sans Frontières has already led to improved therapies.

One, called NECT, is not toxic, and requires less infusions. Another, fexinidazole, is completely oral, taken over a course of ten days. This means fewer lumbar punctures and no need for systematic hospitalization, but it is still relatively complicated to administer and, for many, one lumbar puncture is too many.

One drug, one dose: The new drug candidate is an oral drug taken as a single dose of three pills.

For their trial, published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases, the authors, including Mutombo and Kande, administered acoziborole to over 200 patients with the most common form of sleeping sickness in both early and late stages across ten hospitals in DRC and Guinea.

After 18 months, the drug was able to eliminate the parasite in 198 of the 201 patients who finished the trial. As to the three who were not cured, “we are not sure if that is really a relapse or a reinfection,” Antoine Tarral, who helped develop the drug, told NPR.

The researchers and experts hope that a one-dose therapy will be far more accessible in the rural communities where sleeping sickness predominates.

Adverse events were mild or moderate, the researchers wrote, with fever and fatigue being the most common. Four deaths did occur during the study period, but were not considered related to the treatment.

The researchers and experts hope that a one-dose therapy will be far more accessible in the rural communities where sleeping sickness predominates.

“What is extraordinary with this drug is that it can be given not only in the hospitals but also directly in the villages,” retired University of Sherbrooke sleeping sickness researcher Jacques Pépin told NPR.

While Pépin is bullish on acoziborole, he does have some misgivings about the trial, citing the lack of randomization and a placebo control as well as the relatively small sample size.

Even with the successful trial in hand, there’s likely to be a couple years at least before acoziborole is widely available, Mutombo told NPR.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].