An experimental Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) vaccine has shown promise in mice, and human trials are being planned. By stopping an EBV infection from taking hold, it might also protect us against multiple sclerosis (MS) and certain cancers linked to this common virus.

The challenge: EBV is a contagious herpesvirus — in the same family as the viruses that cause chickenpox, shingles, and cold sores — and it infects over 90% of people, most often when they’re children. It then remains in the body forever, but most people don’t realize it because a latent EBV infection is usually asymptomatic.

EBV infection has been linked to an increased risk of multiple sclerosis and certain cancers.

That doesn’t mean EBV is harmless, though. A large study published in 2022 found that people who’d recently been infected with EBV were 32 times more likely to develop MS — a chronic disorder of the nervous system — than those who hadn’t. This indicates that EBV is likely the cause of MS, although it is a rare complication.

People whose first EBV infection occurs in their teens or early 20s, meanwhile, can develop mononucleosis or “mono” — not only is that disease unpleasant, triggering weeks-long fatigue and fevers, it has also been linked to an increased risk of certain cancers.

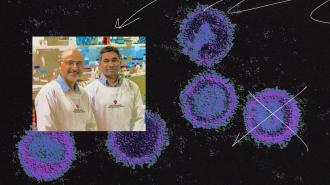

What’s new? There isn’t yet an approved EBV vaccine, but researchers at the QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute in Australia are working on it. They announced that their experimental shot induced a robust immune response in mice, triggering the production of both antibodies and T cells.

“Other vaccine efforts have focused on inducing neutralizing antibodies against the virus, which blocks infection of immune B cells during primary acute infection,” said lead developer Rajiv Khanna.

“But EBV in its latent state hides inside B cells, turning them into tiny virus factories ready to divide and spread whenever our immune defenses are down,” he continued. “It is our killer T cells that detect and control these infected B cells.”

Looking ahead: Triggering an immune response in animal models is just one of the first steps in vaccine development, but the researchers are hopeful they’ll have their EBV vaccine ready for human trials within two years.

If the vaccine can prevent the troublesome herpesvirus from commandeering B cells in people, it may be able to break the chain of events linking an EBV infection to more serious diseases, according to Khanna.

“We think that in susceptible individuals, EBV-infected B cells travel to the brain and cause inflammation and damage,” he explained. “If we can prevent this at an early stage of infection then the infected B cells can’t go on to cause the development of secondary disease like MS.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].