The addition of a cancer vaccine could finally unleash CAR-T cell therapy — a revolutionary treatment for blood cancers — against solid tumors, the most common kind of cancer.

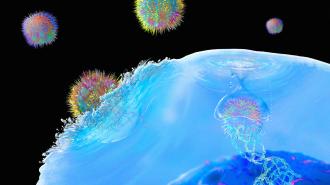

The therapy: CAR-T cell therapy starts with doctors extracting T cells — a special type of immune system cell — from a patient’s blood. The cells are then engineered to display proteins (called “chimeric antigen receptors,” or CARs), which stick to proteins called antigens on cancer cells.

When the cells are infused back into the patient, the CARs bind to cancer cells — and then the T cells help the immune system attack.

The challenge: CARs are designed to bind to one specific antigen — doctors might treat a patient with lymphoma, for example, with a CAR-T cell therapy that binds to an antigen called “CD19” because it’s common and pretty specific to that type of blood cancer.

But researchers haven’t been able to identify antigens that are common on solid tumor cells that aren’t also present on healthy cells.

“In principle, this should apply to any solid tumor.”

Darrell Irvine

That’s a major reason why the only approved CAR-T cell therapies all target blood cancers. Another problem is that tumors surround themselves with chemicals that block the immune system, shutting down the T cells that do find them.

Cancer cells can also evolve during CAR-T cell therapy to stop displaying the target antigen — this phenomenon, known as “antigen loss,” is a problem even when treating blood cancers, allowing the disease to persist despite treatment.

What’s new? MIT researchers have now demonstrated how pairing CAR-T cell therapy with a cancer vaccine boosts its efficacy in mice with two deadly types of solid tumors: glioblastoma, a fast-growing brain cancer, and melanoma, the most serious kind of skin cancer.

“In principle, this should apply to any solid tumor where you have generated a CAR-T cell that could target it,” said senior author Darrell Irvine.

The cancer vaccine helped the CAR-T cell therapy attack tumor cells.

The background: In 2019, the MIT team treated mouse models of glioblastoma with a CAR-T cell therapy, targeting a mutated version of the EGFR receptor, which is found on many — but not all — glioblastoma cells. They then administered a cancer vaccine with the same antigen.

They discovered that this not only helped their CAR-T cell therapy attack tumor cells with the EGFR antigen, but also caused the body to make more T cells targeting other antigens on the glioblastoma cells.

“This vaccine boosting appears to drive a process called antigen spreading, wherein your own immune system collaborates with engineered CAR T cells to reject tumors in which not all of the cells express the antigen targeted by the CAR T cells,” said Irvine.

The latest: For a new study, published in Cell, the researchers tested the CAR-T cell therapy and cancer vaccine combo on mouse models of glioblastoma and melanoma.

They discovered that the vaccine appeared to trigger changes in the CAR-T cells that caused them to produce more of a substance called “interferon gamma.” This stimulates the body’s natural immune system and likely helps it overcome the inhospitable environment around the tumor.

The researchers also learned that, as the CAR-T cells killed the cancer cells, the mouse’s unaltered T cells would learn that other antigens on the cancer cells were red flags. They would then start hunting down and attacking cancer cells with those antigens.

These approaches could dramatically increase the number of patients who receive CAR-T cell therapy.

From this new study, the MIT team also found out that the efficacy of the vaccine-enhanced CAR-T cell therapy is closely linked to the prevalence of the target antigen in the tumor cells.

If 50% of a mouse’s cancer cells expressed the target antigen, for example, the rodent had a 25% chance of having its tumor completely eradicated. If 80% of the cells expressed the antigen, however, the odds of eradication went up to 80%.

Looking ahead: The MIT team has already licensed the tech used for the study to Boston-based biotech company Elicio Therapeutics, which is now preparing the therapy for clinical trials.

Meanwhile, other groups are working to make CAR-T cell therapy a viable option for treating solid tumors by using younger T cells, genetically modifying the cells to be more robust, and pairing them with cancer-killing viruses.

Given that solid tumors account for 90% of all adult cancers, if any of these approaches work, they could dramatically increase the number of patients who receive CAR-T cell therapy — and, hopefully, the number that go into remission following treatment.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].