In his five-plus NFL seasons, Ben Utecht caught 87 passes for 923 yards and three touchdowns. But along the way, throughout a career that included a Super Bowl victory with the Indianapolis Colts, Utecht received five concussions, the last of which left him lying on the field, unconscious for ten minutes. Now, at 36, Utecht is experiencing severe memory loss. He has no recollection of friend’s recent wedding in which he served as a groomsman. The former tight end has decided to write a book for his wife and daughters, so they will understand how much he loves them, just in case those recollections slip away as well.

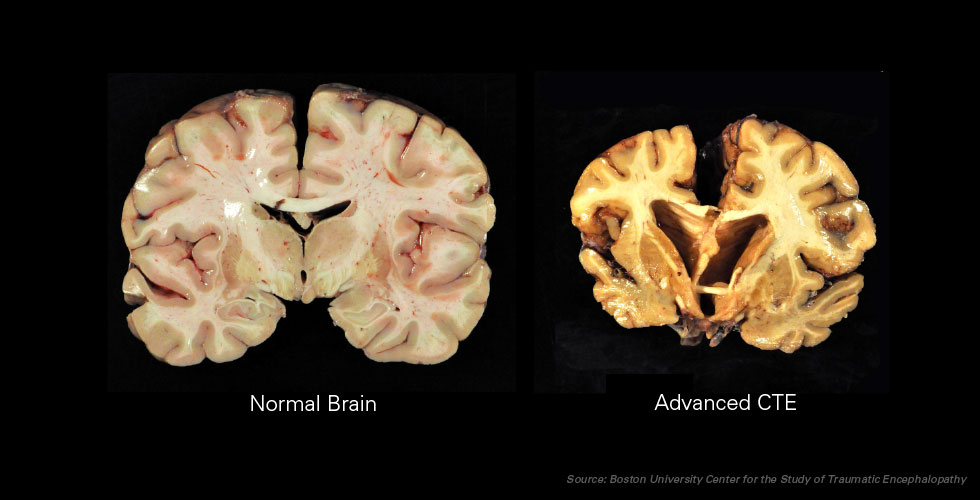

The cooling temperatures and the changing leaves means summer is coming to an end and marks the return of the year’s next official season: football. While football remains entrenched in the forefront of the American psyche, the negative effects of the game are becoming more apparent by the day. According to a recent study by the medical journal JAMA, out of the 111 brains of former football players they autopsied, 99% were found to have chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) — a degenerative brain disease found in people who have suffered multiple traumas to the head. CTE — which can only be formally diagnosed via an autopsy — has an extensive list of symptoms including memory loss, confusion, impaired judgment, aggression, depression, anxiety, impulse control issues and sometimes suicidal behavior.

While the study admits it has flaws — there was no control group and those willing to donate their brains to science are almost certainly more likely to be people who felt they had been suffering from the disease — there is a growing body of research that makes it clear that the status quo is dangerous for players.

The search is on for a solution to what many have called a public health crisis. Measures have been taken to protect players by instituting suspensions and fines for vicious hits targeting the head. The helmets themselves are also changing. It has been known for some time that the way in which players are protected needs to change, and helmet manufacturers are attempting to tackle this problem. Riddell, the leading producer of football helmets, has pioneered a technology it is calling “InSite.” Riddell SpeedFlex helmets equipped with InSite record the hits taken by players in terms of g-forces, location, direction, and severity. The data from the hit is then sent to a handheld device used by the training staff so they can monitor the hits their players have taken in real time.

While the InSite technology is a step in the right direction in understanding better the hits players take, it will not prevent an individual from receiving a concussion in the first place. For decades, the $100 million football helmet market has been dominated by Riddell and Schutt, both of which have focused on improving existing designs instead of heading back to the drawing board. With just two companies cornering the market, there has been little pressure to innovate and as a result, we have seen very few design changes. “There has not been a whole lot of room in which change Riddell and Schutt’s design,” says Ryan Grooms, Notre Dame’s head football equipment manager, “and there is so much liability Riddell and Schutt face that smaller companies wouldn’t be able to handle.” But new players in the helmet market are beginning to emerge. Dave Marver, the CEO of Vicis, a Seattle-based medical technology company and newcomer to the helmet market, thinks his company may have found a solution to the concussion epidemic by scrapping the existing playbook and writing a new one.

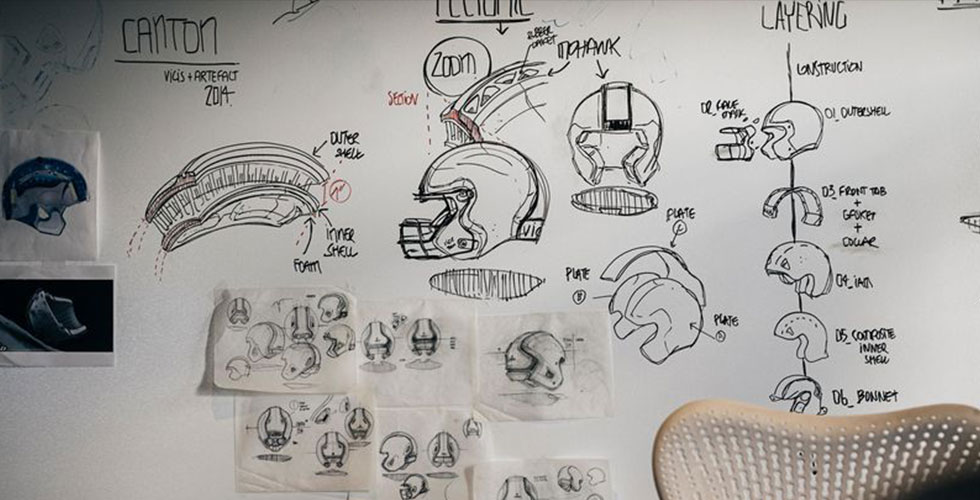

Four years ago, at a neurosurgery conference in Hawaii, the idea for what would become Vicis’ first helmet, the Zero1, was sketched on a napkin by Sam Browd, a pediatric neurosurgeon who was tired of telling young athletes who had suffered numerous concussion that their days of playing contact sports were over. This preliminary design led Browd and his fellow Vicis co-founder Dave Marver to develop the Zero1, Vicis’ revolutionary football helmet. “It’s very difficult, when you have an industry that has been going on for decades, to completely blow up your own product and say this is not the right path,” said Browd in an interview with Sports Illustrated , who also serves as one of the NFL’s unaffiliated neurotrauma consultants for the Seattle Seahawks. “It’s a very expensive and challenging thing.”

The design of the Zero1 can be broken down into four distinct layers. Layer one has been dubbed the Lode Shell which, unlike many of its competitors, absorbs severe hits by deforming at the point of impact, much like a car bumper. The next layer known as the Core, is where the engineers at Vicis earn their money. Acting like an accordion, the Core Layer bends in all directions to help mitigate the effects of collisions with the helmet. The Core Layer is reinforced by the Arch Shell, which is designed to fit the exactitudes of the player’s aspect ratio, that is, the relationship between head length and breadth. Finally, we come to the Form Liner which works in tandem with the Arch Shell to provide a snug and comfortable fit while properly distributing pressure on the head. “The way in which it prevents brain movement is an amazing concept,” says Grooms. “It’s the way of the future.”

However, none of these revolutionary design elements will have any effect in protecting the athlete’s head if it they are not coupled with a proper fit. Vicis has changed the game in this area as well. Traditionally, fit has been determined by measuring the circumference of a player’s head, to which air is then added to the internal padding to close any gaps. Vicis has thrown away this technique and instead measures the athlete’s head length and breadth to achieve a perfect fit. All of these design elements help achieve the ultimate goal of decelerating the player’s head after impact.

While the potential for reinventing the helmet has many people excited, some critics argue that the only way to make football safer is to change the way to game is played. Dr. Robert Cantu, a Boston University neurosurgeon and one of leading voices on brain injuries in sports expressed skepticism in that same Sports Illustrated article that technology will solve the concussion epidemic. He has instead been a strong advocate for instilling more severe punishments for helmet to helmet hits, the leading cause of concussions.

While football leagues can undoubtedly be doing more to limit these kinds of trauma-inducing hits, there is data though to suggest that the type of helmet can make a difference as well. In laboratory testing done by the NFL in conjunction with NFLPA, the Zero1 outperformed its competitors, and the results of the test will appear on a poster posted in every NFL locker room this season.

At $1,500, the unit cost of the Zero1 is out of the price range of of many high school programs, but this fall, expect to see it protecting the heads of football players of top college programs and the NFL. Pro Bowlers Doug Baldwin and Richard Sherman will be sporting the Zero1 on their heads come fall, as will players from at least twenty of the top NCAA programs. Among them will be title contender Notre Dame, whose players have so far reacted extremely positively to the performance of the Zero1 on the field, according to Grooms. The ultimate goal for Vicis though includes getting the Zero1 on to the heads of high school and youth players, but for now it is focused on proving the superiority of the design. “Year one is not about making money. It’s about making the helmet as good as we can,” said Marver in an interview with Bloomberg .

From its beginning, Vicis has operated under the motto that even one concussion is a concussion too many. “You think, OK, it’s just a helmet, it is what it is, and there’s nothing you can really do about it,” Baldwin said when interviewed by Sports Illustrated . “But being exposed to this new technology, you realize there is something we can do here; there is something that can be improved.”