How does one measure innovation? It’s not like examining a stock market index. Should we look at citations? Who inventors claim to have been inspired by? Or is it more of a “feeling”?

A new paper published in American Economic Review: Insights offers a novel way to judge how inventions influence those that come after them based on language. It also gives a glimpse at where innovation was occurring over the last 200 years of American history and points toward some of the most innovative inventions of all time.

Using language to measure innovation

One of the more common ways to determine how important a certain invention or patent turned out to be is to review how many citations it received in future patents. While this is a decent idea, it’s got problems. First, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office only consistently recorded citations after 1947, long after many great inventors had done their best work. Second, where we do have citations, they are often incomplete. For instance, an inventor or patent clerk may have been unaware of other similar patents.

These shortcomings are why the team turned to the language describing a patent for their new model.

The model relies on natural language processing techniques to review patents for related terms in the technical explanation included with each patent. If two patents contain shared terms, like “electricity” or “petroleum,” they can be considered at least somewhat related. The novelty of a term, like when it is used for the first time, is also accounted for, as is how often the term is used afterward. The system allows for the similarity of two patents to be measured and for networks of relationships to be mapped — though it turns out that most patents have little to do with each other.

Using the model, it is also possible to create an “importance measure” determining how substantial an invention was in terms of its being related to inventions that came shortly afterward. This technique was validated when it gave high scores to universally celebrated inventions, such as the telegraph, internal combustion engine, and stem cell technology.

Of course, no method is perfect. This model failed to give high scores to a few major innovations, namely pasteurization and Morse code. However, barring a few slip-ups, the method is able to identify novel and important inventions across American history.

What were the most important inventions?

While they don’t provide a specific list, the authors do give examples of inventions that were both novel and set the course for future innovations.

Perhaps chief among these examples was Nikola Tesla’s Electro-Magnetic Motor (patent 381,968). Before this, there were no patents making reference to alternating current but many afterwards did so. Tesla’s AC motor is also used as the primary example of an invention that causes a “scientific regime shift” — that is, once AC was invented, it became commonplace in electrical technology, increasing the comparative importance of the first patent.

Another invention the authors point to is patent 4750, an improved sewing machine by Elias Howe. While it is not significantly related to any prior patents, it is closely associated with 16 patents issued over the next decade. Many of these were held by Howe and his compatriots who created the first patent pool.

Not all extremely important inventions arose seemingly out of nowhere. Patent 493,426 for one of the first motion picture projectors is closely related to two prior inventions and a dozen more in the following decade. Among them was the predecessor to the modern film camera.

Other highly innovative patents they identity include the Wright Brothers’ patent for a “flying machine” (patent 821,393), several related to concrete, many related to antibiotics and their production, all of Enrico Fermi’s patents dealing with nuclear reactors, Robery Noyce’s microchip (patent 2,981,877), and nylon (patent 2,071,250).

The history of innovation

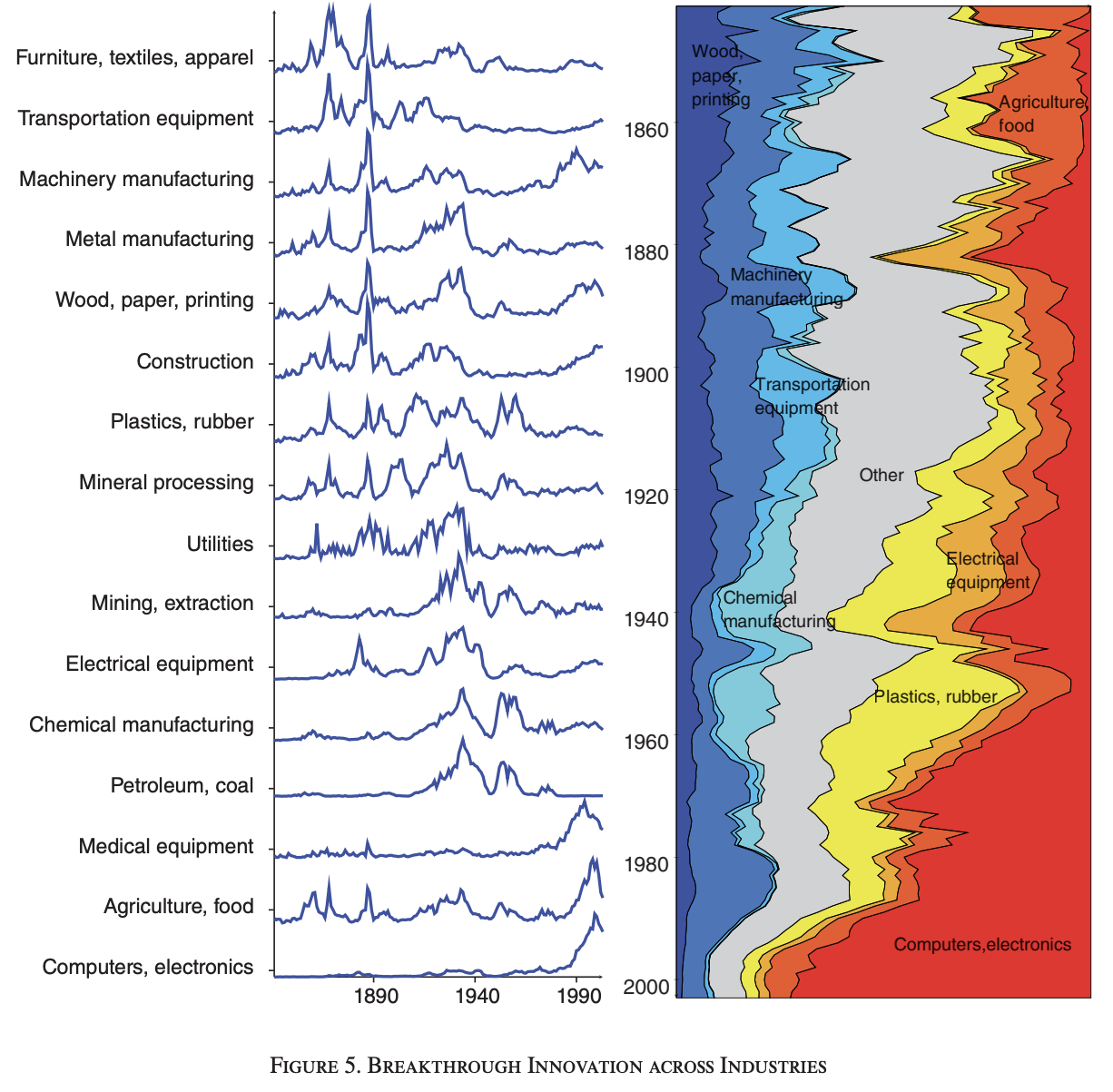

The authors’ method also showed in which industries and when major innovations were occurring throughout U.S. history.

As shown, breakthrough tech shifts over time. In the early 19th century, as industrialization took hold, most of the groundbreaking work was in transportation and textiles. Later in that century, electric devices became possible and a number of inventions were produced. Chemicals and petroleum dominate the mid-20th century, while computers have enjoyed the attention of great inventors more recently.

This article was originally published on our sister site, Big Think. Read the original article here.