A close read of image data from the Magellan spacecraft’s visit to Venus has revealed evidence of volcanic activity on our sister planet.

Taken in the mists of the ancient past — the early 1990s — the images show an expanded volcanic vent nearly overflowing with a supremely rock ‘n roll lava-filled lake, like something right out of Revelation, although they are unsure if it was still liquid or not.

The new discovery may provide proof of an active world, despite its lack of moving continental plates, which cause most of Earth’s fiery eruptions.

The paper, published in Science, foretells the possible insights to come when NASA’s next Venus mission, VERITAS, launches.

“NASA’s selection of the VERITAS mission inspired me to look for recent volcanic activity in Magellan data,” study author Robert Herrick, a research professor at the University of Alaska-Fairbanks (UAF) and member of the VERITAS team, said in a statement from NASA.

“I didn’t really expect to be successful, but after about 200 hours of manually comparing the images of different Magellan orbits, I saw two images of the same region taken eight months apart exhibiting telltale geological changes caused by an eruption.”

A sinister sibling: Despite being red and barren, Mars gets the most love of our planetary neighbors, and it has a primary place in both science and culture.

But it is Venus that is truly the closest analog to Earth, both because it is the nearest to us, and in its similar size and density. The comparison takes a dramatic turn from there, however.

Venus is Earth’s “evil twin,” a sinister sibling whose thick, toxic atmosphere, scored by clouds of acid, smothers its blistering surface — making it hotter than even Mercury, hot enough to melt lead. That lethal sky weighs down with an atmospheric pressure 90 times stronger than the Earth’s, as if deep beneath the sea.

It’s a hellish world — fitting for its nickname as “the morning star” — where everything familiar is off; even the sun rises in its west, thanks to its unusual reverse rotation.

Why study the surface? Venus differs from Earth in another important way: it lacks the tectonic plates that move around our planet’s surface, where 95% of Earth’s volcanoes are located. While scientists have known about the existence of Venusian volcanoes for some time, whether or not they are still active — and how active — is unknown.

Estimates “have been speculative, ranging from several large eruptions per year to one such eruption every several or even tens of years,” Herrick said in an UAF release.

“While this is just one data point for an entire planet, it confirms there is modern geological activity.”

scott hensley

Old images, new insights: Launched from the space shuttle Atlantis in 1989, Magellan was the first spacecraft to image the entire surface of Venus, ending its successful mission by plunging into the atmosphere in one last data-gathering go, before incinerating after ten hours.

While researchers have had the image data for decades, it was previously very difficult to study. Because the images were taken at different points, from different angles, they can’t really be searched using automated efforts, the study authors wrote — hence the need to search by hand.

“This was a needle-in-a-haystack search with no guarantee that the needle exists,” Herrick told CNN.

But the researchers believe they did find that needle.

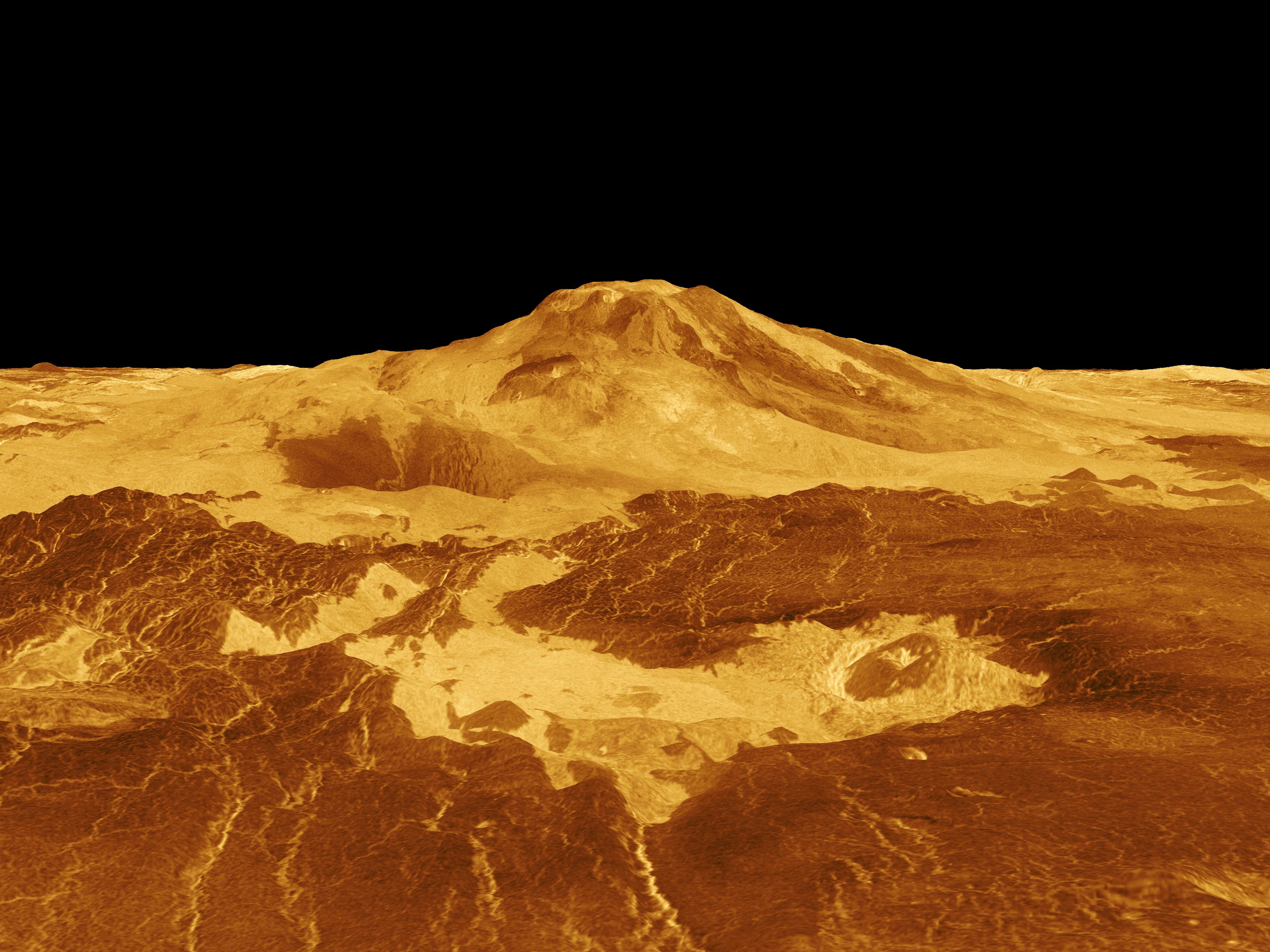

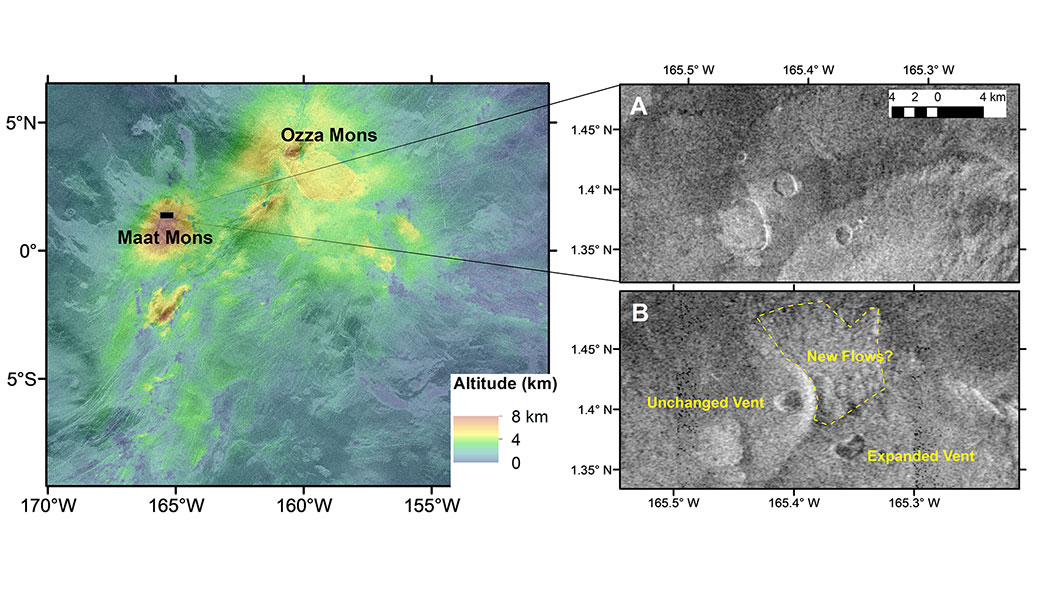

The team focused on a region of Venus called Atla Regio, an expansive highland containing two of the planet’s largest volcanoes, Ozza Mons and Maat Mons; changes in Maat Mons provided the possible evidence.

In the first image, taken in mid-February 1991, a volcanic vent associated with Maat Mons looked to be circular. It covered an area of less than 1.1 square miles, with tall, sloping interior walls. On the outside walls were markings that suggested drained lava, a hint that it might have been active.

In the second image, taken from mid-October of 1991, the vent looks vastly different. It nearly doubled in size, taking on a misshapen form, and its interior seemed filled to the top with lava.

To test their hypothesis, Herrick teamed up with Scott Hensley, the project scientist for VERITAS. They created computer models to simulate different geological scenarios that could have caused the change, like landslides.

“Only a couple of the simulations matched the imagery, and the most likely scenario is that volcanic activity occurred on Venus’ surface during Magellan’s mission,” Hensley said in NASA’s release. “While this is just one data point for an entire planet, it confirms there is modern geological activity.”

Unless the researchers were staggeringly lucky, the results suggest volcanic activity occurs every couple of months or so, Herrick told CNN. That would put it on a similar schedule to well-known Earth volcanoes like Kilauea in Hawaii, or those in the Galapagos and Canary Islands.

The cold water: The study comes with some caveats, however. There’s another scenario that the authors believe may have caused the vent’s dramatic transformation. An earthquake could have collapsed the vent’s walls, but similarly sized earthquakes on Earth, however, have always come with volcanic activity, the team noted.

The other problem may be a bigger one: whether the change really did happen at all.

Because the two images were taken from two different perspectives, they were quite difficult to compare, and compounding the problem is the low resolution of the images.

That does cloud the results, Scott King, a geophysicist at Virginia Tech who studies Venus, told Nature.

“Proof is in the eye of the beholder,” King said.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].