Using images from the Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers have confirmed that a comet first spotted in images from 2010 is the largest comet ever observed.

“We’ve always suspected this comet had to be big because it is so bright at such a large distance,” said study co-author David Jewitt from UCLA. “Now we confirm it is.”

The challenge: Comets are small objects in our solar system made of bits of rock, ice, and dust. When a comet’s orbit takes it closer to the sun, some of its ice becomes a gas. Together with loosened dust, it forms a fuzzy cloud around the comet, called the “coma.”

It’s difficult to determine where the coma ends and the comet’s solid nucleus begins when a comet is far away, so astronomers couldn’t say for sure whether Comet Bernardinelli-Bernstein was the largest comet when it was first imaged in 2010, at a distance of 3 billion miles from the sun.

The largest comet: Since 2010, Bernardinelli-Bernstein has been barreling our way from the edge of the solar system at 22,000 miles per hour — it’s now only about 2 billion miles away from the sun.

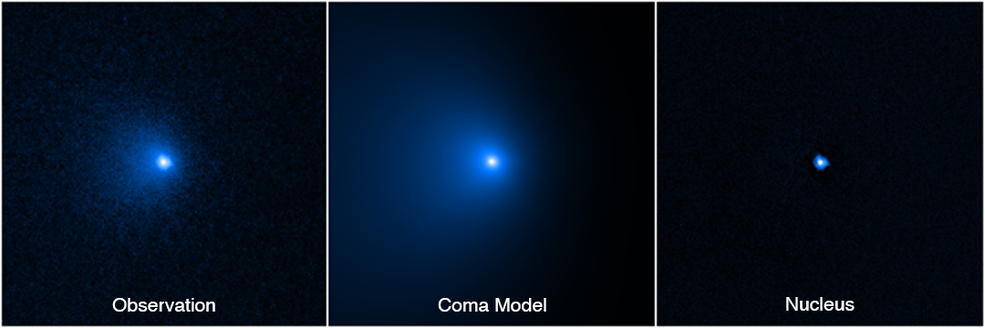

In January 2022, astronomers used Hubble to take five images of the closing comet. They then made a computer model of its coma, adjusting it to match the Hubble images.

The coma’s glow was then removed from images, and by comparing the brightness of the nucleus that remained to observations from Chile’s ALMA telescope, the astronomers were able to determine Bernardinelli-Bernstein’s diameter.

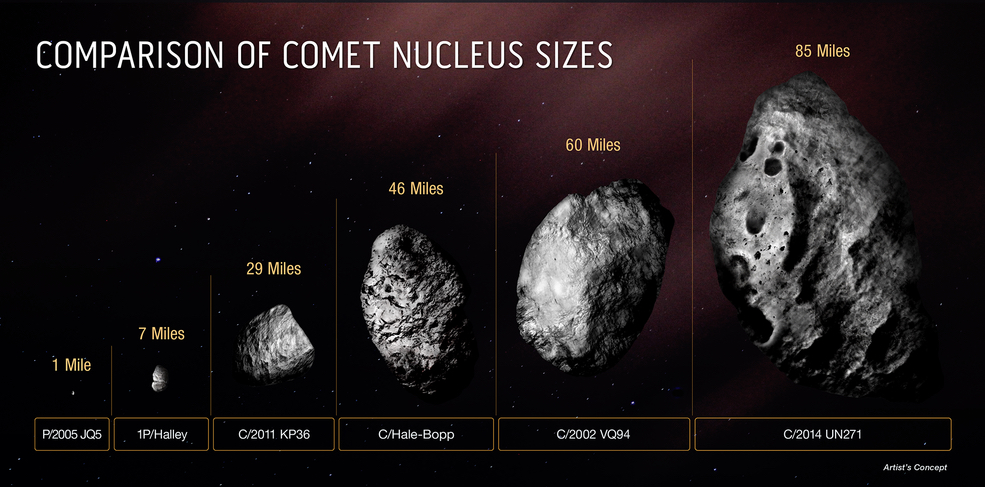

The astronomers estimate that the comet is 80 miles across. That’s far bigger than the previous record holder for largest comet, which is just 60 miles wide, and about twice the size of Rhode Island, which is 48 miles long and 37 miles wide.

The comet’s mass is an estimated 500 trillion tons — that’s about a hundred thousand times more massive than the comets we see closer to the sun.

Looking ahead: In 2031, Bernardinelli-Bernstein will be about 1 billion miles away from the Sun — that’s the closest it’ll get to us. Its 3-million-year-long elliptical orbit will then start taking it away from the sun. When it’s about half a light-year away, it’ll swing back in our direction.

Astronomers will continue to observe Bernardinelli-Bernstein as it gets closer, as studying it can help us better understand the Oort Cloud — a spherical, comet-packed area that encases our entire solar system and played a role in its evolution.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].