We like to think of technological innovation as a gradual, steady, and fairly linear process. However, this is not necessarily the case. Archaeological excavations throughout the world reveal that, once in a while, ancient civilizations developed inventions that were decades if not centuries ahead of their time.

It is sometimes said that these inventions rival or outmatch modern science. This, too, is a misconception. While many ancient super technologies — from Roman concrete to Damascus steel — were once lost, they have since been recreated by present-day researchers. Usually, any difficulty in recreating them stems from the lack of original instruction rather than an inability to comprehend the invention itself.

Equally erroneous is the notion that ancient civilizations stumbled upon these technologies by accident, or that they were designed by idiosyncratic geniuses who were not representative of their day and age. Although many inventors mentioned in this article were indeed considered geniuses, they cannot and should not be separated from their surroundings. Their work is not anachronistic, but a testament to the ingenuity and scientific potential of their respective civilizations.

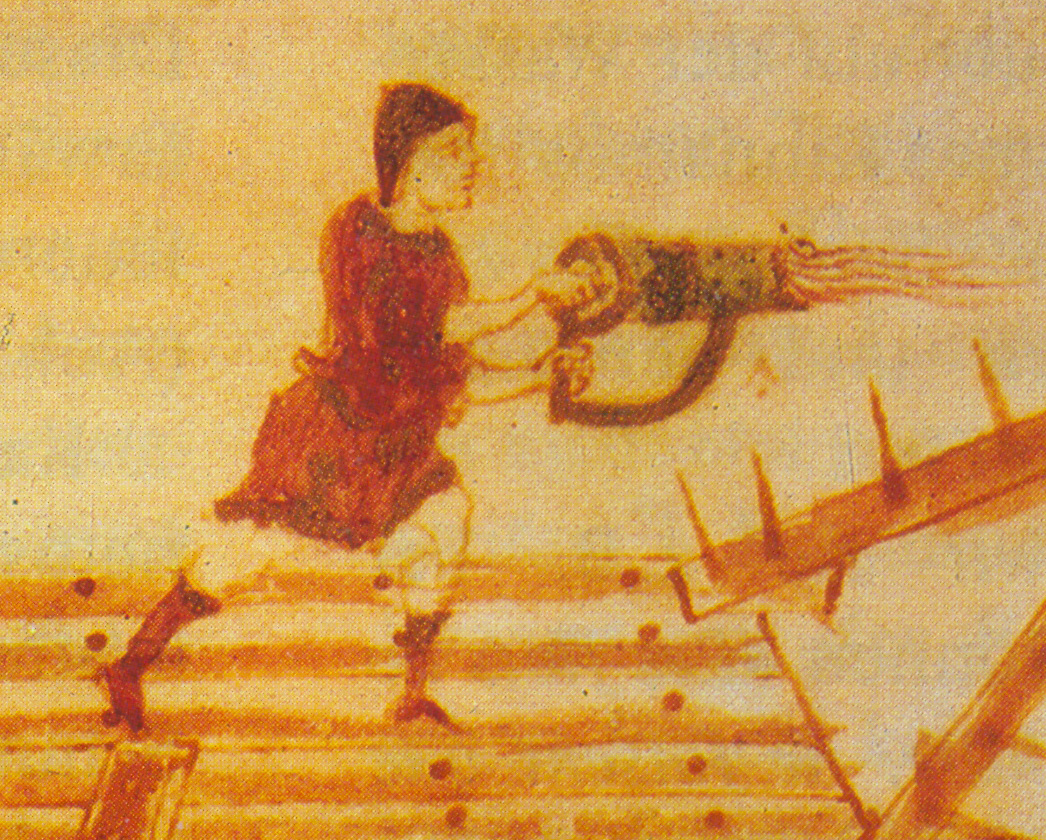

Greek fire: flames that don’t go out

When the Muslim fleet of the Umayyad Caliphate attempted to lay siege to the Byzantine city of Constantinople in 674, their ships were doused in flames. At first, the Muslims were not alarmed; fire was often used in naval warfare and could be put out easily with cloth, dirt, or water. This, however, was no ordinary fire. Once ignited, it could not be extinguished, and after the entire fleet had burned down, even the sea itself was set ablaze.

The Umayyad Caliphate met its doom at the hands of a new military invention known as Greek fire, Roman fire, liquid fire, or sea fire, among many other names. No recipe survives, but historians speculate it might have involved petroleum, sulfur, or gunpowder. Of the three, petroleum seems the likeliest candidate, as gunpowder didn’t become readily available in Asia Minor until the 14th century, and sulfur lacked the destructive power described by Arab observers.

However, what makes Greek fire so impressive is not the chemistry of the fire itself but the design of the pressure pump the Byzantines used to launch it in the direction of their enemies. As the British historian John Haldon discusses in an essay titled “‘Greek Fire’ Revisited,” researchers struggle to recreate an historically accurate pump that could have propelled its content far enough to be of any use during naval battles, where enemy ships may be dozens or even hundreds of meters removed from one another.

Antikythera mechanism: a cosmic clock before Copernicus

The Antikythera mechanism was found off the coast of Antikythera, a small Greek island located between Kythera and Crete. Its discovery occurred in 1901, when divers in search of sea sponges stumbled upon a deposit of sunken wreckage from classical antiquity. The titular contraption was incomplete and in poor condition, but seemed to have consisted of some 37 bronze gears stored inside a wooden box.

Scholars initially speculated that the Antikythera mechanism, which was found to be over 2,200 years old, had functioned as an ancient computer. This hypothesis was written off as being too improbable, only to be reaffirmed by more detailed studies from the 1970s. The current consensus holds the mechanism was an orrery: a model of the solar system that calculates and tracks celestial time.

CT scans reveal the contraption’s mindboggling complexity. A 2021 attempt at replicating the Antikythera mechanism referred to it as “a creation of genius — combining cycles from Babylonian astronomy, mathematics from Plato’s Academy, and ancient Greek astronomical theories.” It could calculate the ecliptic longitudes of the moon and sun, the phases of the moon, the synodic phases of the planets, the excluded days of the Metonic Calendar, and the Olympiad cycle, among a myriad of other things.

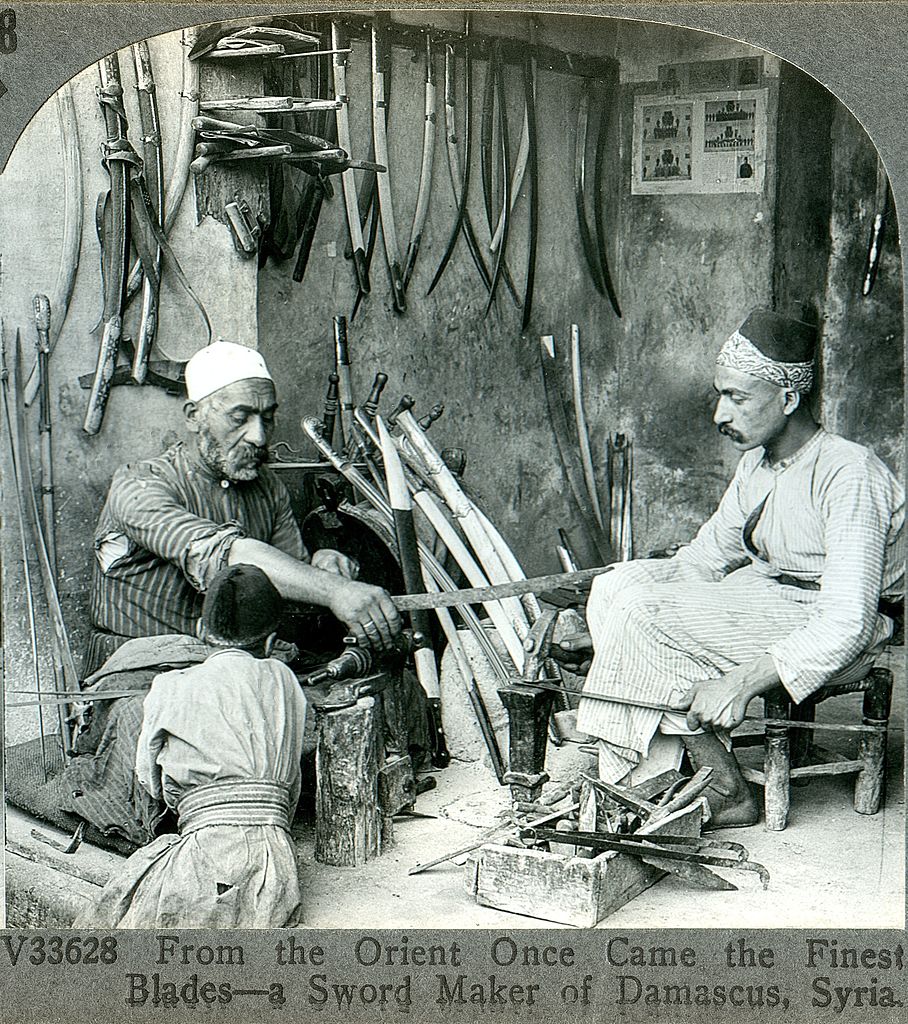

Damascus steel: swords that will not dull

Damascus steel swords originated in the Middle East during the 9th century and were renowned for their appearance as well as their durability, being multiple times stronger and sharper than the Western swords used during the Crusades. Their name, derived from the Arabic word for “water,” references not only the Syrian city from which they hailed but also the flowing pattern that adorns their surface. This pattern was created during a unique forging process where small ingots of wootz steel sourced from India, Sri Lanka, or Iran were melted with charcoal and cooled at an incredibly slow rate.

The demand for Damascus steel remained high for centuries, but gradually diminished as swords were replaced with firearms in armed conflicts; by 1850, the secrets of its production process appeared lost.

Interest in the swords was revitalized by C.S. Smith, a metallurgist who worked on the Manhattan Project. Unfortunately, Damascus steel can never be recreated authentically as wootz steel is no longer available. Since the 1960s, however, researchers have tried to develop new forging techniques that achieve similar results. This development is still ongoing; one study from 2018 claims adding small levels of carbide-forming elements like Vanadium (V) is the way to go.

The Houfeng Didong Yi: the world’s first seismoscope

Created almost 2000 years ago, the Houfeng Didong Yi holds the honor of being the world’s first seismoscope. Its place of origin was China, a country that has been plagued by earthquakes for as long as its inhabitants can remember. Its creator was Zhang Heng, a distinguished astronomer, cartographer, mathematician, poet, painter, and inventor who lived under the Han Dynasty from 78 to 139 AD.

The design of the Houfeng Didong Yi is as functional as it is aesthetically pleasing. The mechanism consists of a large, decorated copper pot. The pot was fitted with eight tubed projections that were shaped to look like dragon heads. Below each dragon head was placed a copper toad with a large, gaping mouth.

“Zhang’s seismoscope,” one 2009 study from Taiwan explains, “is respected as a milestone invention since it can indicate not only the occurrence of an earthquake but also the direction to its source.” While primary sources are unclear as to how the seismoscope actually worked, researchers suggest that vibrations caused a pendulum inside the pot to swing, causing a small ball to release through a dragon head and into the mouth of its corresponding toad, indicating the direction of an earthquake.

Roman concrete: cement that does not crack

Many architectural projects of ancient Rome would not have been possible without Roman concrete. Also known as opus caementicium, Roman concrete was a hydraulic-setting cement mix consisting of volcanic ash and lime that, in the words of Pliny the Elder, bound rock fragments into “a single stone mass” and made them “impregnable to the waves and every day stronger.”

The earliest-known reference to Roman concrete dates to 25 BC and comes from a manuscript titled Ten Books on Architecture, written by the architect and engineer Vitruvius. Vitruvius recommends builders use volcanic ash from the city of Pozzuoli in Naples, called pozzolana or pulvis puteolanus in Latin. Pozzolana should be mixed with lime at a ratio of 3:1 or 2:1 if the construction is under water.

When Vitruvius wrote his Ten Books on Architecture, Roman concrete was still considered a novelty and used sparingly. This changed in 64 AD, when an urban fire destroyed two thirds of the imperial capital. As the survivors set out to rebuild, Nero’s building code called for stronger foundations. The switch to Roman concrete — which, true to Pliny’s words, does not crack — enabled the construction of architectural projects like the Pantheon, the world’s oldest and biggest unreinforced dome.

Baghdad battery: a rudimentary taser (for pain relief)

Archaeologists use the term “Baghdad battery” to refer to a ceramic pot, copper tube, and iron rod that were found in Iraq near what was once the capital of both the Parthian and subsequent Sasanian Empire. They believe the three distinct objects once fitted together to create a single device. The purpose of this device, which seems to have been capable of generating electricity, remains unclear.

Wilhelm König, director of the Iraq Antiquities Department — the same organization whose employees first found the battery — originally theorized that it was used as a galvanic cell to electroplate objects. This theory, though widely accepted upon its initial publication, does not hold up as no electroplated objects from the same time period and region have been discovered so far.

In 1993, Paul Keyser from the University of Alberta in Edmonton formulated a different, less anachronistic and therefore more plausible hypothesis. The battery, he argued, functioned not as a galvanic cell but a local analgesic that could relieve pain through transmitting an electrical charge. In doing so, it would have replaced electric fish, which in Greco-Roman societies were sometimes used to treat headaches, gout, and other conditions.

This article was reprinted with permission of Big Think, where it was originally published.