In the field of advanced prosthetics, much of the conversation revolves around giving amputees the independence that they lost by restoring mechanical function of lost limbs. To date, this has looked like smarter bionic legs for easier walking, robotic arms that have grabbing or holding functions, and other cyborg body enhancements.

But it seems we’ve been skipping a crucial aspect of losing a limb – the sense of touch.

In all seasons of our Superhuman Show, we’ve focused on the technology that has helped patients regain health and mobility. But the heart of Superhuman is highlighting the medical technology advancements that bring out the human in all of us. And what’s more human than touch?

In the final episode of this season of Superhuman, we explore the groundbreaking technology of electric skin, also known as, e-dermis.

The Johns Hopkins Bioengineering Lab Researcher That’s Advancing Prosthetic Skin

Luke Osborn is a Ph.D candidate and researcher at Johns Hopkins Biomedical Engineering Lab, and for the last several years, he has been developing e-dermis.

E-dermis is a flexible sensor that can mimic the sensory qualities of human skin. Luke explains, “If you were to look at a little cross section of your skin and see all the different receptors you would notice that they’re not all in one layer. They’re offset and some are higher up in the skin than others. And so we built the e-dermis to actually mimic that.”

The spark for Luke’s electric skin research was the phenomenon that nearly 80% of amputees experience – phantom limb syndrome.

Phantom Limb Pain Fuels the Feeling

For those of you asking, “right, what is phantom limb pain again?” consider it the ongoing, lingering sensations coming from a limb that is no longer there. Phantom limb syndrome can present in the form of pain, however amputees also may have the sensation of the limb still functioning or even something touching the missing limb. And the sensations that amputees feel are 100% real.

While the limb may be gone, the part of the brain connected to that missing limb is still there, and still, to at least some degree, able to function.

Electric Skin, Touching For the Very First Time

Andrew Rubin is a subject of Luke’s study. 15 years ago, Andrew experienced an injury that left his hand and foot without any sensation or mobility. A few years ago, he decided to have them therapeutically amputated.

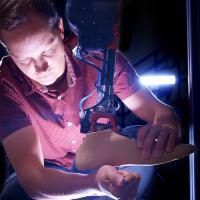

Seen in the video, Luke must map the the nerves in Andrew’s arm so that he can send signals from the e-dermis sensor to Andrew’s brain. Luke explains, “After an amputation, the sensory nerves that go through your arm up into your brain generally are still there. And so what we’re trying to do is find where they are.”

In this figure from Luke Osborn’s research, you can see how tactile information from the e-dermis is passed through the control center and stimulator, and into the brain.

“It’s hard to explain what the feeling is like… There’s this, I guess… a visualization that goes on. You reimagine what wasn’t there before.”

Andrew Rubin

Underneath the Epidermis

So what gives this electric sensory patch the ability to feel? Luke Osborn’s research focuses specifically on pressure perception and innocuous and noxious – or nonpainful and painful – sensations.

This patch of prosthetic skin works very similarly to the way our own fingertips detect painful or unsafe objects. We often detect something that’s sharp as being dangerous, and release our grip. While something that is round is does not pose the same threat.

By reading an object based on its curvature, the electric skin is able to determine that a decrease in radius (something that is more sharp) has a higher correlation to pain. And as a result, the brain tells the prosthetic to let go.

In this second figure from Luke’s research, the pain reflex is identified by the amount of time it takes to release the sharp object, compared to the rounder objects above.

The Future for Prosthetic Skin

E-dermis is still being heavily researched. But as seen today, even in an early stage, this electric skin has the possibilities to restore more than just a physical function to amputees’ lives.

“During these experiments it’s not an experience of loss that I experience. I experience the presence of ‘That’s where my thumb is.’ This is filled with possibility.”

Andrew Rubin

We tend to think of our skin as what separates us from the world. But it’s also what connects us to it. This research holds the promise of allowing prosthetic users that feeling of connection that so many of us take for granted.

Feeling inspired? Meet the Superhuman that’s testing one of the most advanced bionic limbs on the planet, and how he’s inspiring our future “amplified humans”. Watch Emerging Cyborg now: