Over the past year or so, generative AI models such as ChatGPT and DALL-E have made it possible to produce vast quantities of apparently human-like, high-quality creative content from a simple series of prompts.

Though highly capable – far outperforming humans in big-data pattern recognition tasks in particular – current AI systems are not intelligent in the same way we are. AI systems aren’t structured like our brains and don’t learn the same way.

AI systems also use vast amounts of energy and resources for training (compared to our three-or-so meals a day). Their ability to adapt and function in dynamic, hard-to-predict and noisy environments is poor in comparison to ours, and they lack human-like memory capabilities.

Our research explores non-biological systems that are more like human brains. In a new study published in Science Advances, we found self-organising networks of tiny silver wires appear to learn and remember in much the same way as the thinking hardware in our heads.

Imitating the brain

Our work is part of a field of research called neuromorphics, which aims to replicate the structure and functionality of biological neurons and synapses in non-biological systems.

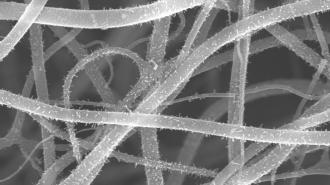

Our research focuses on a system that uses a network of “nanowires” to mimic the neurons and synapses in the brain. These nanowires are tiny wires about one thousandth the width of a human hair. They are made of a highly conductive metal, such as silver, typically coated in an insulating material like plastic.

Nanowires self-assemble to form a network structure similar to a biological neural network. Like neurons, which have an insulating membrane, each metal nanowire is coated with a thin insulating layer.

When we stimulate nanowires with electrical signals, ions migrate across the insulating layer and into a neighbouring nanowire (much like neurotransmitters across synapses). As a result, we observe synapse-like electrical signalling in nanowire networks.

Learning and memory

Our new work uses this nanowire system to explore the question of human-like intelligence. Central to our investigation are two features indicative of high-order cognitive function: learning and memory.

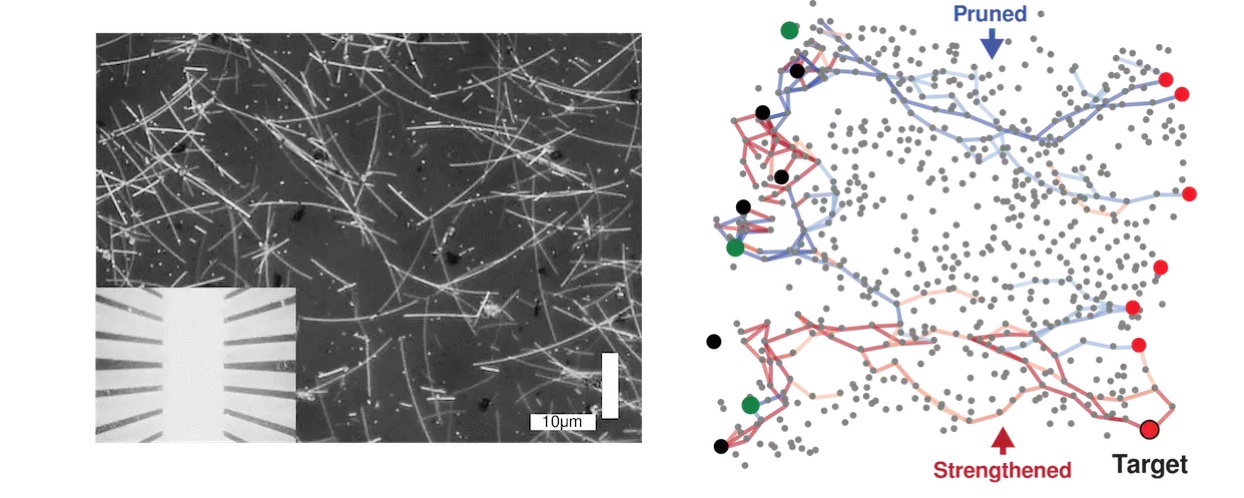

Our study demonstrates we can selectively strengthen (and weaken) synaptic pathways in nanowire networks. This is similar to “supervised learning” in the brain. In this process, the output of synapses is compared to a desired result. Then the synapses are strengthened (if their output is close to the desired result) or pruned (if their output is not close to the desired result).

We expanded on this result by showing we could increase the amount of strengthening by “rewarding” or “punishing” the network. This process is inspired by “reinforcement learning” in the brain.

We also implemented a version of a test called the “n-back task” which is used to measure working memory in humans. It involves presenting a series of stimuli and comparing each new entry with one that occurred some number of steps (n) ago.

The network “remembered” previous signals for at least seven steps. Curiously, seven is often regarded as the average number of items humans can keep in working memory at one time.

When we used reinforcement learning, we saw dramatic improvements in the network’s memory performance.

In our nanowire networks, we found the formation of synaptic pathways depends on how those synapses have been activated in the past. This is also the case for synapses in the brain, where neuroscientists call it “metaplasticity”.

Synthetic intelligence

Human intelligence is still likely a long way from being replicated.

Nonetheless, our research on neuromorphic nanowire networks shows it is possible to implement features essential for intelligence – such as learning and memory – in non-biological, physical hardware.

Nanowire networks are different from the artificial neural networks used in AI. Still, they may lead to so-called “synthetic intelligence”.

Perhaps a neuromorphic nanowire network could one day learn to have conversations that are more human-like than ChatGPT, and remember them.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.