Translation isn’t simply a matter of swapping one word for a corresponding word in another language. A high-quality translation requires the translator to understand how both languages string thoughts together and then use that knowledge to create a translation that maintains the linguistic nuances of the original, which native speakers effortlessly understand.

As difficult as that process is, it’s nothing compared to the challenge of translating an ancient language into a modern tongue. These translators must not only resurrect extinct languages from written sources but also have intimate knowledge of how the cultures that produced those sources evolved over centuries. If that weren’t enough, their sources are often fragmented, leaving crucial context lost to the ages.

Because of this, the number of people capable of translating languages from antiquity is small, and their best efforts are often outpaced by the volume of texts unearthed by archeologists.

Take ancient Akkadian. This early Semitic language is one of the best attested from the ancient world. Hundreds of thousands, by some accounts more than a million, Akkadian texts have been discovered and today lie in museums and universities. Many have even been digitized online. Each one has the potential to teach us about the life, politics, and beliefs of the first civilizations, yet this knowledge remains locked behind the time and manpower necessary to translate them.

To help change that, a multidisciplinary team of archaeologists and computer scientists has developed an artificial intelligence that can translate Akkadian almost instantly and unlock the historic record preserved in these 5,000-year-old tablets.

Akkadian lost (and found)

Akkadian was the mother tongue of the Akkadian Empire, which arose around 2300 B.C. through the conquests of its founder, Sargon the Great. As a spoken language, Akkadian would eventually split into Assyrian and Babylonian dialects before being completely supplanted by Aramaic early in the first millennium BC. Today, it is a truly extinct language, without even daughter languages to carry on its legacy.

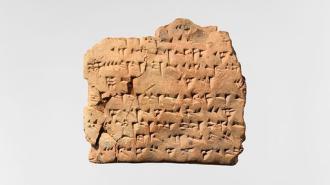

As a written language, however, Akkadian proved more enduring. The empire borrowed the cuneiform script of its predecessor, the Sumerian civilization. This writing system used a reed stylus to impress wedge-shaped glyphs into wet clay tablets before baking them (hence the name cuneiform, which literally means “wedge-shaped” in Latin). Even after Aramaic supplanted Akkadian as the common language of the region, scholars continued to write in Akkadian cuneiform into the first century AD — even in antiquity, it seems, scholars and academics were incredibly stubborn.

This traditional mindset had an unintended benefit for modern archeologists, too. While cuneiform could be written on papyrus, it was more often scribed onto clay or stone. These materials stand up much better to the fires and floods that ravaged their pithy peers. And while time is cruel to all things — archeologists rarely discover cuneiform tablets in mint condition — this is one reason why Akkadian writing may be so well-attested in the historic record.

“Ironically, destructive conflagrations have preserved some of ancient Mesopotamia’s greatest libraries — because they were made of clay. In contrast, all of ancient Egypt’s papyrus libraries have burnt or crumbled to dust, though many individual codices survive,” linguist Steven Roger Fischer writes in A History of Writing.

Even with such linguist riches, properly translating these ancient libraries is no small feat. Beyond the challenges already mentioned, the Akkadian language is polyvalent. That is, its cuneiform signs can have several different readings depending on how each one functions in a sentence. There are many reasons for this development, but according to Fischer, one reason the Akkadians never simplified was that they “appeared to be bound to tradition and a self-imposed efficiency.” That traditional mindset led them to continue using Sumerian script for a language very different from Sumerian. (When it comes to historical scholarship, you win some, you lose some.)

As such, translating Akkadian is a two-step process. First, scholars must transliterate the cuneiform signs. That is, they take the cuneiform and rewrite it using the similar-sounding phonetics of the target language. An example most readers will be familiar with is the Arabic word الله, which translates into English as “God” but transliterates as “Allah.” This transliteration is the closest the Latin alphabet can get to producing the word as it sounds in Arabic. Scholars then take their transliteration of the text and translate it into a modern language.

Fast-acting AI for instant results

As you can imagine, that can be a long and laborious process — one that takes years of training and dedication to learn to do well. To help speed things along, the research team developed a neural machine translation model for Akkadian cuneiform, the same technology under the hood of Google Translate.

The team trained the AI model on a sample of cuneiform texts from the Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus and taught it to translate in two distinct ways. First, the AI model learned to translate Akkadian from transliterations of the original texts. It also learned how to translate cuneiform symbols directly. More specifically, it translated Unicode glyphs of cuneiform texts that were generated by another time-saving tool that automatically produces Unicode from an image of an original tablet.

The AI model then had to figure out how to handle the nuances of the sample’s various genres — for example, the difference between literary works and administrative letters — as well as how to handle the changes found in cuneiform script over the millennia it was used. The AI model was then tested using the bilingual evaluation understudy 4 (BLEU4), an algorithm used to appraise machine-translated text.

In its transliteration to English test, the team’s AI model scored 37.47. In its cuneiform to English test, it scored 36.52. Both scores were above their target baseline and in the range of a high-quality translation. And there was a surprising result: The model was able to reproduce the nuances of each test sentence’s genre. While this wasn’t one of the researcher’s goals, they note in the study that it may open possibilities for uses beyond translation.

“In almost every instance, whether the [translation] is proper or not, the genre is recognizable,” the team writes. “A promising future scenario would have the [model] show the user a list of sources on which they based their translations, which would also be particularly useful for scholarly purposes.”

The team published their results in the peer-reviewed PNAS Nexus. They also released their research and source code on GitHub at Akkademia.

The past’s future looks brighter

As promising as the initial results are, there is still work to be done. In both cases, some of the test sentences were mistranslated. And like other AI models, this one is prone to hallucinations — moments where the response has no connection to the source. In one instance, the human translator produced the sentence “Why should we (also) conduct the lawsuit before a man from Libbi-Ali?” The AI’s translation: “They are in the Inner City in the Inner City.” (A bit off.)

All told, the AI model works best when it is translating short- to medium-length sentences. It also does better with more formulaic genres, like royal decrees and administrative records, than literary genres such as myths, hymns, and prophecies. With more training on a larger dataset, the researchers note in the study, they aim to improve its accuracy. In time, they hope their AI model can act as a virtual assistant to human scholars. The AI can provide the raw translation quickly, while the scholar can refine it with their knowledge of historic languages, cultures, and people.

“Hundreds of thousands of clay tablets inscribed in the cuneiform script document the political, social, economic, and scientific history of ancient Mesopotamia. Yet, most of these documents remain untranslated and inaccessible due to their sheer number and limited quantity of experts able to read them,” the team writes in the study.

“This is another major step toward the preservation and dissemination of the cultural heritage of ancient Mesopotamia.”

This article was reprinted with permission of Big Think, where it was originally published.