Reproductive tech startup Orchid is now offering whole genome sequencing for embryos, giving prospective parents and their doctors information that could lead to healthier and more successful pregnancies — but not everyone is convinced it’s worth the cost.

The challenge: Infertility is incredibly common, affecting 1 in 6 people worldwide, and when the “old-fashioned way” of getting pregnant doesn’t work, some turn to in vitro fertilization (IVF).

Doctors will use sperm to fertilize an egg, creating an embryo. They then implant one or more of these embryos in a womb to develop. (Usually, the cells come from the people trying to become parents, but sometimes the sperm or egg are donated.)

Infertility is incredibly common, affecting 1 in 6 people worldwide.

IVF can increase the chance of pregnancy, but it’s not guaranteed to work. It’s also expensive — the average per-round cost in the US is $12,400, and many people need to go through multiple rounds before they have a successful pregnancy.

In an attempt to tip the odds in their favor, some prospective parents have their embryos screened before they are implanted, looking for genetic variants that could cause the pregnancy to fail or increase the chance the baby is born with a genetic disorder.

This process — preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) — gives them the opportunity to choose the healthiest embryos, but because it typically involves sequencing less than 1% of an embryo’s genome, there’s a limit on the amount of information it provides.

What’s new? Reproductive tech startup Orchid is now offering whole genome sequencing for embryos at IVF centers in several major US cities, providing prospective parents with health reports that take into account 99% of an embryo’s genome.

“This is the future of preventive medicine and family planning.”

George Church

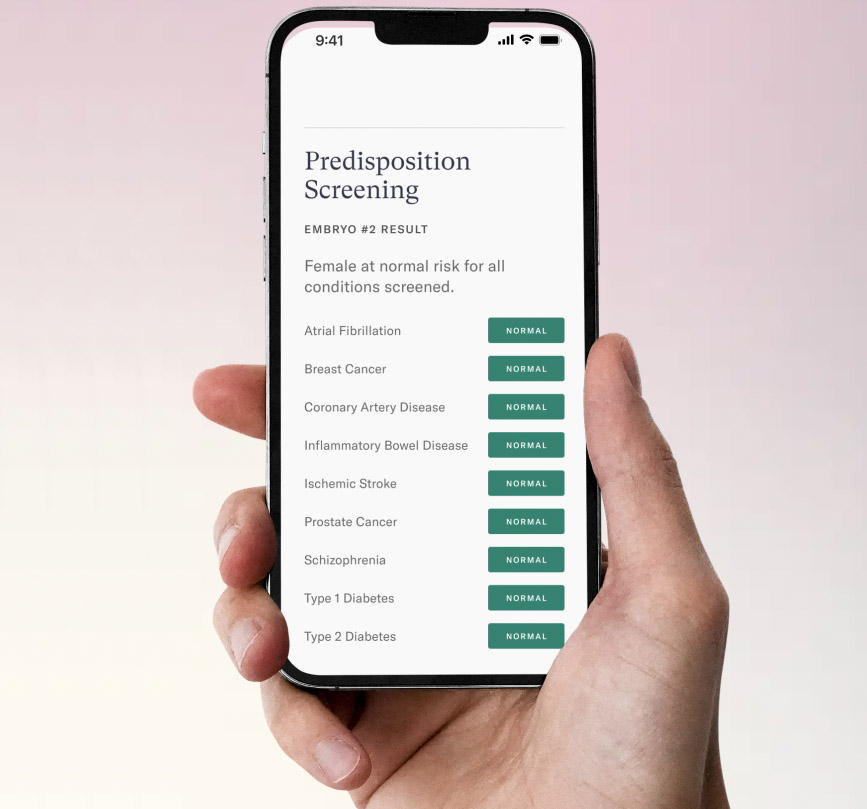

Orchid sequences the embryo’s genome, then screens it for variants linked to more than 1,200 monogenic disorders (ones caused by a single genetic variant). The report also notes the risk of an embryo developing polygenic disorders, which are more complex to predict because they are linked to effects of multiple genes.

“The ability to read over 99% of an embryo’s DNA is groundbreaking,” said George Church, a pioneer of genome sequencing and an Orchid investor and advisor. “For the first time, comprehensive screening is made possible for genetic forms of neurodevelopmental disorders, congenital anomalies, and cancers prior to pregnancy.”

“This is the future of preventive medicine and family planning,” he added.

The controversy: Church may be fully onboard, but other researchers have voiced concerns about Orchid and companies like it providing prospective parents with risk scores for polygenic diseases when it’s not clear that the scores are actually all that accurate.

While Orchid has shared a paper on the preprint server bioRXiv validating the technique it uses to sequence the genomes of embryos, it hasn’t proven the information leads to healthier pregnancies or babies. Seemingly the only way to do that would be to compare people who choose embryos based on its reports to those who fly blind, but there’s no sign such a study is in the works.

“Part of my worry is how upfront [Orchid] is when they’re counseling parents of the likely benefit of these procedures,” Peter Kraft, an epidemiology professor at Harvard, told the LA Times in 2021.

Others are concerned that using whole genome sequencing to screen embryos for diseases is a step toward “designer babies,” with parents selecting embryos based on the likelihood it will lead to a child that is smart, athletic, or some other characteristic they value.

The ethics of this advanced embryo screening get even murkier when you consider that the only people with access to the service will be those who can afford it — Orchid charges $2,500 per embryo, on top of the standard cost of IVF.

Looking ahead: Noor Siddiqui, Orchid’s founder and CEO, told CNBC that the company expects the cost of its reports to fall as it scales up. She also pushed back on the idea that her company shouldn’t be providing parents with the genetic information it’s capable of collecting.

“The way that you can use that information is really up to you, but it gives a lot more control and confidence into a process that, for all of history, has just been totally left to chance,” Siddiqui told CNBC.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].