In the two decades since the completion of the Human Genome Project — when scientists created the first draft of a complete human genome — personal genetics has exploded into a multibillion-dollar industry.

It started as an exploration into finding an individual’s ancestral heritage. Now, there is a buffet of options for consumer genetic analysis that go beyond ancestry — like nutrigenomics (DNA based diets) or companies like Orchid, a preconception genetic testing company that launched earlier this year.

When it comes to decoding your genome, you have a menu of options that range from less than $50 to several thousand dollars — including whole genome sequencing.

But what do these options mean, and how do you know what you’re getting?

Back to basics

DNA is the chemical code of all life. It is arranged in a double helix — a twisted spiral ladder. Each rung of the ladder is a base pair, or a set of two letters, composed of either A, T, C, or G.

Every human genome has 3.2 billion base pairs. To put that in perspective, the world’s longest novel, Marienbad My Love by Mark Leach, is only 17 million words, or a little over 109 million characters. Still, the book doesn’t come close to the human genome.

23andMe vs. whole genome sequencing

When it comes to analyzing your DNA, companies like 23andMe use genotyping, rather than sequencing. Genotyping looks for differences in genes that are only a small part of your total DNA. Researchers hone in on a specific region, looking for a known genetic variant that hints at a disease or ancestral heritage. They’ve identified where to look using studies that scan the genomes of many people who have that disease or heritage in common, looking for similar genetic variations.

“A good question to always ask is: ‘To whom am I being referenced? Who am I being compared to? I think this testing probably doesn’t serve all populations equally, because our data set is based largely on white people.”

Ellen Macnamara

Instead of getting a comprehensive picture of an individual’s genome, researchers compare your genetic variants or differences against a reference database.

The information gleaned from that comparison is only as good as the database. Unfortunately, the reference database for consumer DNA test kits is primarily of European descent. Because of this persistent Eurocentric bias, advances in consumer genetic testing often don’t apply to everyone.

“A good question to always ask is: ‘To whom am I being referenced? Who am I being compared to?’” says Ellen Macnamara, a Genetic Counselor at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). “I think this testing probably doesn’t serve all populations equally, because our data set is based largely on white people.”

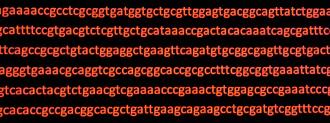

While genotyping figures out which genetic differences an individual has, whole genome sequencing reads out the exact sequence of DNA. Whole genome sequencing deciphers the letters in the entire genome, all those As, Ts, Cs, and Gs — all 3.2 billion base pairs.

It might look something like this:

23andMe and AncestryDNA genotyping tests only about 0.02% of your DNA. By comparison, whole genome sequencing maps out as close to 100% as possible, generally going over the genome several times to make sure they got it all accurately.

Macnamara says genes are like the encyclopedia that put you together; and genome sequencing is like opening that document and hitting spellcheck. Each lab might have a slightly different version of spellcheck, and they can set parameters of that spellcheck.

“If I’m seeing a patient who has a skeletal disease, let’s say, I’m interested in the places in that document that we know are involved in building bones and skeleton, so I actually only spellcheck on pages 150 to 175, because that captures those genes,” she says. “Spellcheck” would highlight genetic variants or mutations.

“I like this analogy because spellcheck doesn’t catch everything. So genome sequencing can have all of the data there, and it still might not find all of the errors, or all of the variants.”

Ok, but what does this tell me?

It is easy to assume that if whole genome sequencing maps out nearly all of a person’s DNA, the test results could answer all the questions that genotyping does, and more. But Macnamara says that is not the case — what you get out of it depends on the professional analysis.

“With respect to the way the analysis works, genome sequencing would not usually return the ancestry results that a direct to consumer ancestry testing would,” she says, because the list of letters doesn’t give you the algorithm that interprets those results.

Most people seek whole genome sequencing if they have symptoms of a rare undiagnosed genetic disease and are looking for an explanation.

Macnamara says most genetic counselors, like herself, support individuals’ decision to get genetic information on “medically actionable conditions” when they undergo genome sequencing.

“There is a list of about 60 genes — things like increased risk for cancer syndromes or increased risk for certain types of heart disease. The reason we’ve selected those genes is because we know of steps you can take to mitigate your risk,” she says.

For example, if a genetic test indicates an increased risk for breast cancer, the individual could opt for early and frequent screening. Macnamara also says, on the other hand, researchers know the genes that indicate a risk for Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s, but they don’t typically provide an otherwise healthy patient with those results because there aren’t any actionable steps they can take in advance.

“The field [of genetic counseling] is not in the practice of returning risk results for non-treatable adult onset conditions,” she says. “We do have some data from the Huntington’s disease arena that shows receiving information like that should be done with some very specific counseling, and support setups.”

In fact, 90% of persons who are aware that they are at risk for Huntington’s disease refuse to undergo the genetic test, owing to the lack of Huntington’s disease therapies. For most, it’s more difficult to live with the knowledge that they will get Huntington’s (and there is nothing they can do about it) than it is to live with the unknown.

And, even though genetic research has made significant progress in the recent past, so much about what makes us how we are is still a mystery.

Macnamara thinks of genes like a recipe for baking a cake. “DNA is just the starting place. And to the extent that we understand that, right now, we don’t understand all of the other things that affect why everybody bakes a slightly different cake with the same recipe.”

*We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].*