A first-of-its-kind heart transplant performed on a baby at Duke University Hospital could one day help others avoid organ rejection while reducing the need for immunosuppressant drugs, which leave patients at high-risk of infection for the rest of their lives.

“This case has implications for more than just heart transplantation — it could change the way that many solid organ transplants are done in the future,” Allan D. Kirk, chair of the Department of Surgery at Duke University School of Medicine, told Duke Today.

Immunosuppressant drugs leave transplant recipients at much higher risk of infection.

The challenge: The immune system’s main job is to detect and attack any foreign invaders that enter the body. If those invaders are viruses or bacteria, this helps us avoid getting sick — but if the foreign entity is a transplanted organ, the attack will cause the organ to fail.

To prevent this, organ recipients have to take drugs that suppress their immune systems. These drugs leave them at much higher risk of infection and must be taken for their entire lives — if they stop, they risk organ rejection.

The treatment could help patients avoid organ rejection with less dependence on immunosuppressant drugs.

The idea: In October 2021, the FDA approved Rethymic, a Duke-developed treatment for children born without a thymus — that’s the gland that trains our bodies to produce T cells, which help regulate the immune system.

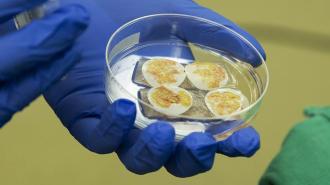

The treatment processes donated thymus tissue and implants it into a patient so that it can prompt their bodies to create T cells.

The Duke team theorized that implanting a bit of thymus tissue from the same donor as the needed organ might help prevent organ rejection — the T cells produced by the thymus tissue would treat the organ as the body’s own and prevent the immune system from attacking it.

“This case could change the way that many solid organ transplants are done in the future.”

Allan D. Kirk

The surgery: After successful animal studies, Duke received permission to test the procedure in a person, and Easton Sinnamon turned out to be a perfect candidate — he needed a new heart and his thymus wasn’t working properly, meaning he’d need the Rethymic treatment anyway.

After giving Easton his new heart in August 2021, when he was six months old, the team waited two weeks and then performed the thymus tissue implantation. About six months after that, tests confirmed that the tissue was creating T cells as hoped.

Easton has since celebrated his first birthday, and while he is still taking immunosuppressant drugs to prevent organ rejection, his doctors hope to start tapering him off the meds in the next several months.

The big picture: If Easton continues to thrive without those drugs, it’ll suggest that donated thymus tissue could one day help transplant recipients avoid organ rejection without compromising their immune systems.

“If this can be extrapolated to patients who already have a functioning thymus, it could potentially allow them to restructure their immune systems to accept transplanted organs with substantially less dependence on anti-rejection medication,” Kirk said.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].