A new CRISPR system that makes “soft” edits to DNA was proven to be far more effective and precise than the traditional version in experiments with fruit flies.

If it translates to humans, it could be a safer, more effective way to cure countless genetic diseases.

The challenge: It was only a decade ago that we learned CRISPR-Cas9 could be harnessed as a gene-editing tool, and in that short time, the molecular scissors have been used to create everything from disease-resistant fruit to neanderthal mini-brains.

CRISPR isn’t a perfect tool — it can be inefficient and make off-target edits.

The tech’s most powerful application, though, is in healthcare — more than 6,000 human diseases are caused by genetic mutations, and CRISPR gives researchers a way to correct those mutations, curing people of their diseases permanently.

But CRISPR isn’t a perfect tool. While correcting a mutation that causes a disease, it can create other mutations (called “off-target” changes). It can also be inefficient, editing too few cells successfully to effectively treat a disease.

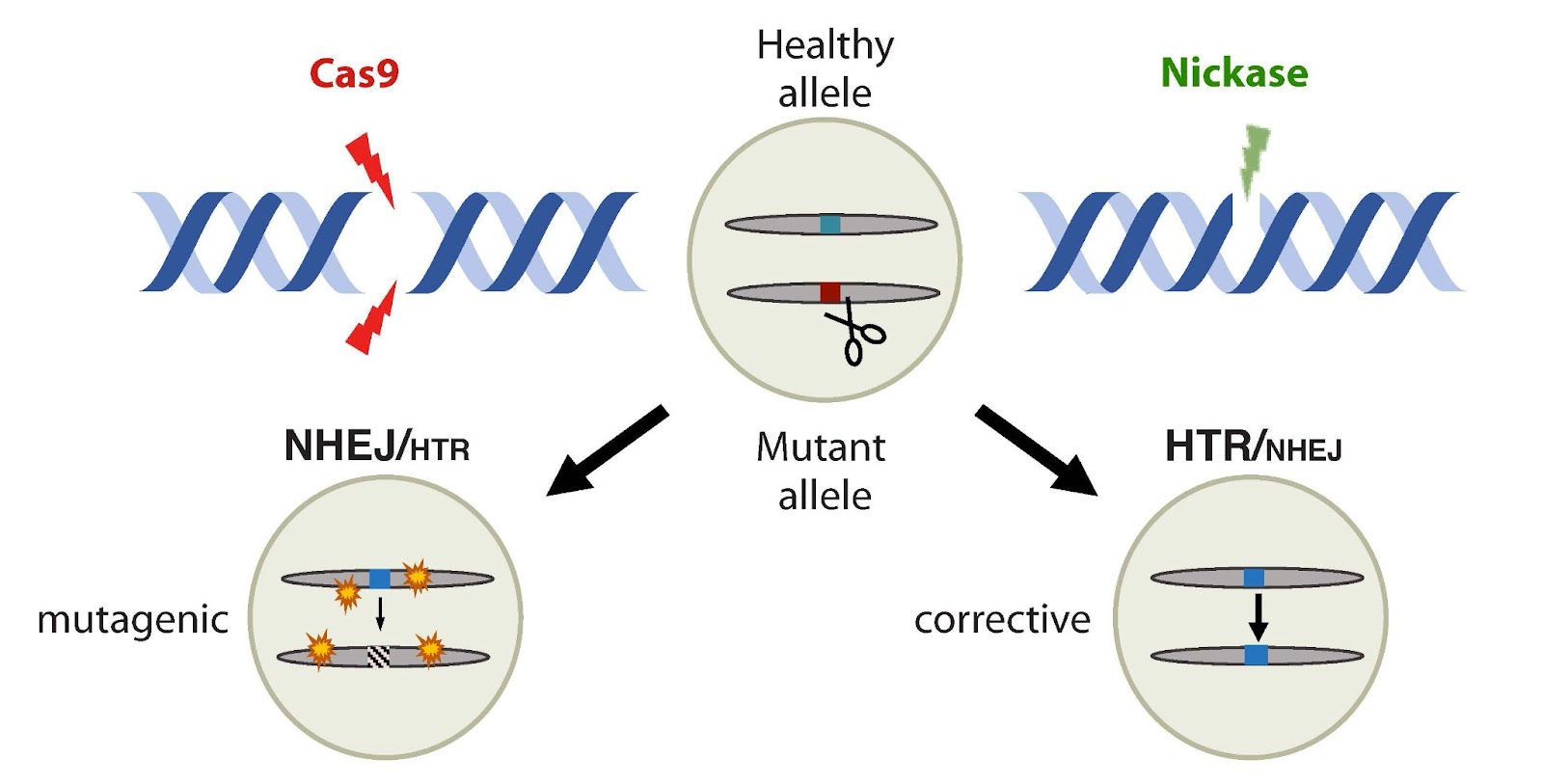

New CRISPR system: Humans typically have two copies of every gene (one inherited from each parent), but a mutation in just one copy is sometimes enough to cause a disease.

UC San Diego researchers have taken advantage of our genetic backup copies with a new CRISPR system, which uses variants of Cas9 known as “nickases” to target just the mutated gene while leaving the healthy one alone.

It does this by “nicking” a single side of the DNA double helix, rather than cutting through both strands.

The cell’s natural repair system then uses the other chromosome’s copy as a guide when repairing the nicked strand — effectively copying over the mutated gene with the healthy version.

“It relies on very few components and DNA nicks are ‘soft,’ unlike Cas9, which produces full DNA breaks often accompanied by mutations,” said researcher Ethan Bier.

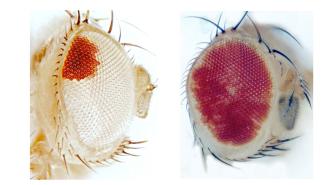

Fly eyes: To test the new CRISPR system, fruit flies were given a mutation that makes their eyes entirely white.

When CRISPR-Cas9 was used to correct the mutation, it edited 20-30% of the insect’s cells — parts of their eyes regained their normal red color, but they were still mostly white.

“I could not believe how well the nickase worked — it was completely unanticipated.”

Sitara Roy

The new CRISPR system edited 50-70% of the cells and turned most of the eye red. It also caused far fewer off-target mutations than the CRISPR-Cas9 system.

“I could not believe how well the nickase worked — it was completely unanticipated,” said lead author Sitara Roy.

Looking ahead: So far, all we know is that this new CRISPR system is better and safer at correcting a specific mutation in flies, and we’ll need to know a lot more before it can be trialed in people.

“We don’t know yet how this process will translate to human cells and if we can apply it to any gene,” said researcher Annabel Guichard.

But, in principle, the researchers think they could get it to work with some tweaks: “Some adjustment may be needed to obtain efficient [repair] for disease-causing mutations carried by human chromosomes.”

If the system works as well in people as in flies, it could be a big upgrade to CRISPR-Cas9 — and might help us reach a future in which gene editing has cured more than just a handful of diseases.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].