Researchers in Wisconsin have grown human eye cells in the lab — and then intentionally infected them with rabies. The results of the experiment proved that these cells can communicate with one another — a huge achievement on the path to using lab-grown cells to reverse blindness.

The challenge: Vision loss is often due to problems with the retina, a thin layer of tissue at the back of the eye. There, cells called “photoreceptors” convert light into electrical signals that can be sent down the optic nerve to the brain for processing.

Many of the most common retinal diseases, such as macular degeneration, are progressive and incurable — once diagnosed, all patients can do is try to slow their vision loss.

The hope is that the lab-grown eye cells might one day replace cells damaged by retinal disease.

The idea: In 2011, researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison announced that they’d managed to coax stem cells into growing into three-dimensional structures, called “organoids,” which resembled retinas in early stages of development.

The UW-Madison team has continued to develop those organoids over the past decade in the hope that their lab-grown eye cells might one day replace cells damaged by retinal disease, giving people back their lost vision.

Step by step: Before that could happen, though, the researchers needed to be confident that the lab-grown eye cells would behave as hoped once implanted in patients’ eyes.

Last year brought good news on that front: the team reported in a pair of studies that photoreceptors isolated from their organoids responded to light like natural ones and reached out to one another with their axons — the long wires that nerve cells use for communication.

“The last piece of the puzzle was to see if these cords had the ability to shake hands with other retinal cell types.”

David Gamm

One question still remained unanswered, though.

In a healthy eye, retinal cells send electrical signals to the tips of their axons. Those signals then cross a small gap, called a “synapse,” to reach the tip of another cell’s axon — and as of 2022, the researchers still didn’t know if their lab-grown eye cells could make that leap.

“The last piece of the puzzle was to see if these cords had the ability to plug into, or shake hands with, other retinal cell types in order to communicate,” said David Gamm, head of the lab developing the eye organoids.

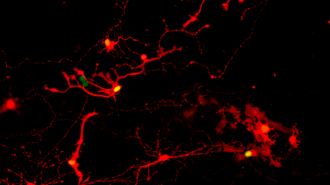

Rabies revelation: To find the answer, the UW-Madison team broke apart their organoids. They then gave the eye cells a week to extend their axons toward each other before exposing some of the cells to a rabies virus (modified so that any infected cells would be easily visible).

When they later checked the lab-grown eye cells, they found that the virus had made the jump between pairs of cells, indicating that they were able to form functional synapses.

Photoreceptors were most adept at making the connections, which is particularly exciting news given that damage to those cells is behind two leading causes of blindness: retinitis pigmentosa and age-related macular degeneration.

“It’s all leading, ultimately, to human clinical trials, which are the clear next step.”

David Gamm

Looking ahead: Now that the UW-Madison team knows that the lab-grown eye cells will function like the natural kind on both an individual and systemic level, the scientists are eager to see whether the cells can help reverse vision loss in people.

“We’ve been quilting this story together in the lab, one piece at a time, to build confidence that we’re headed in the right direction,” said Gamm. “It’s all leading, ultimately, to human clinical trials, which are the clear next step.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].