A drug used against the herpes virus since the 1960s can weaken a deadly superbug enough to allow the immune system to kill it — offering new hope in the battle against antibiotic resistance.

The challenge: Our immune system can usually kill any harmful bacteria that enter our bodies before we even know they’re there. If it can’t, though, we can take antibiotics, drugs that kill bacteria or stop them from reproducing so the immune system can catch up.

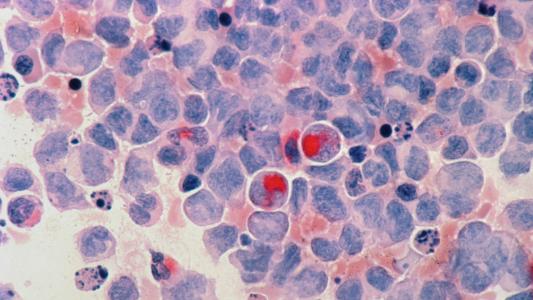

Decades of misuse and overprescribing has given many bacteria time to evolve resistance to antibiotics, leaving us almost defenseless again. Klebsiella pneumoniae — a bacteria that can cause respiratory, intestinal, and urinary tract infections — is one of those superbugs.

While certain strains of K. pneumoniae are only resistant to one type of antibiotic, others are resistant to most common antibiotics — some studies have found that up to 50% of people infected by those strains will die from the infection.

“This very simple system then enabled us to test thousands of molecules.”

Pierre Cosson

The drug: Rather than trying to develop a new antibiotic to combat K. pneumoniae infections, in a new study, researchers at the University of Geneva (UNIGE) exposed resistant strains of the bacteria to hundreds of existing drugs.

They then introduced the drugged bugs to an amoeba, which feeds on bacteria using the same mechanism our immune cells use to kill them.

“We genetically modified this amoeba so that it could tell us whether the bacteria it encountered were virulent or not,” said lead researcher Pierre Cosson. “This very simple system then enabled us to test thousands of molecules and identify those that reduced bacterial virulence.”

They found that edoxudine, an anti-herpes drug first discovered in the 1960s, can weaken the surface layer of K. pneumoniae, which could make it easier for the immune system to kill.

“This avenue seems all the more promising as the virulence of Klebsiella pneumoniae stems largely from its ability to evade attacks from immune cells,” said Cosson.

“[It’s] a subtle strategy, but one that could prove to be a winner in the short and long terms.”

Pierre Cosson

Looking ahead: Edoxudine worked on the most virulent strains of K. pneumoniae — and at concentrations lower than those used to treat herpes — but we won’t know for sure that it can help treat infections until it’s tested in people.

Because edoxudine has already undergone development, it should be easier to get those trials approved than if the UNIGE team wanted to test a brand-new antibiotic. The fact that edoxudine doesn’t outright kill K. pneumoniae could work in our favor, too.

“[This] limits the risk of developing resistance, a major advantage of such an anti-virulence strategy,” said Cosson. “Sufficiently weakening the bacteria without killing them is a subtle strategy, but one that could prove to be a winner in the short and long terms.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].