A new gene therapy could dramatically change the lives of people with the rare liver disorder Crigler-Najjar syndrome, replacing their current 12-hours-a-day treatment regimen with a one-and-done injection. It adds to a growing number of gene therapies that are effectively treating the liver.

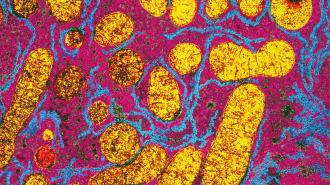

The challenge: When red blood cells break down at the end of their life, they produce a toxic substance called “bilirubin.” The liver, whose job is to filter out toxic substances from the blood, uses an enzyme called UGT1A1 to convert the bilirubin into a form that can be removed from the body.

But people with the extremely rare genetic disorder Crigler-Najjar syndrome have a mutation in the UGT1A1 gene that causes their body to produce too little or none of the enzyme. This allows bilirubin to build up in their blood, which causes jaundice, brain damage, or can even lead to death.

To break down the bilirubin in their blood, people with Crigler-Najjar syndrome sit under blue lights for 10-12 hours every day.

Currently, the only ways to treat Crigler-Najjar syndrome are a liver transplant or phototherapy.

A transplant depends on the availability of a compatible donor organ, and it requires patients to take immunosuppressants for the rest of their lives. Phototherapy requires them to sit under blue lights, which break down the bilirubin in their blood, for 10-12 hours every day. That can severely decrease their quality of life.

What’s new? French biotech company Généthon has now published the results of a small trial testing its in-development gene therapy for Crigler-Najjar syndrome, which uses a harmless virus to deliver an unmutated copy of the UGT1A1 gene into the cells of the liver.

During the trial, five women between the ages of 21 and 30 received either a low or high dose of the therapy as a single IV injection. While the low dose didn’t have the desired effect, the high dose reduced bilirubin to non-toxic levels, and it appears to be permanent — the three women who received it have now gone 18 months or longer without phototherapy.

No major side effects were reported, though four of the women did see another of their liver enzymes increase to levels near the top of the normal range. That was likely the result of their immune systems reacting to the viral vector, and it was treated with steroids.

The three women who received the gene therapy have now gone 18 months or longer without phototherapy.

Looking ahead: In January, Généthon launched the pivotal part of their trial, which will see children as young as 10 treated with the gene therapy at sites in France, the Netherlands, and Italy.

“If the results of the pivotal part confirm the efficacy of our gene therapy for Crigler-Najjar syndrome, we will be able to move on to product license application and making the treatment available to patients, providing them with significantly improved quality of life,” said Frédéric Revah, CEO of Généthon.

The trial joins a small but growing roster of approved and experimental gene therapies that are effectively targeting diseases originating in the liver, such as hemophilia, amyloidosis, and hypercholesterolemia.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].