This article is an installment of Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Thursday morning by subscribing here.

Humans might not be able to regenerate entire limbs, like salamanders and starfish, but we can regrow our livers — surgeons can remove up to two-thirds of the organ, and the healthy tissue left behind will regrow back to nearly full size within a few months.

But that is assuming there is healthy tissue left behind.

If too much of a person’s liver is damaged, their only treatment option may be a liver transplant. There aren’t enough donor livers to meet the demand, though, and as a result, at least 1700 people in the US die on the liver transplant waiting list every year.

A new treatment about to be trialed in humans for the first time could end this shortage — by turning a single donor liver into “mini livers” capable of saving 75 or more lives.

Mini liver incubator

Our bodies want to have a certain amount of healthy liver tissue. If the liver is damaged, it will send out chemical signals that encourage healthy liver cells to multiply. Once the desired liver mass is reached, other mechanisms kick in to stop the regrowth.

If there aren’t enough healthy liver cells left, these distress calls are futile — but LyGenesis, a Pittsburgh-based biotech company, has found a way to take advantage of them to restore liver function, which it has demonstrated in several animal studies.

“The lymph node disappears entirely, and what you’re left with is a highly vascularized miniature liver.”

Michael Hufford

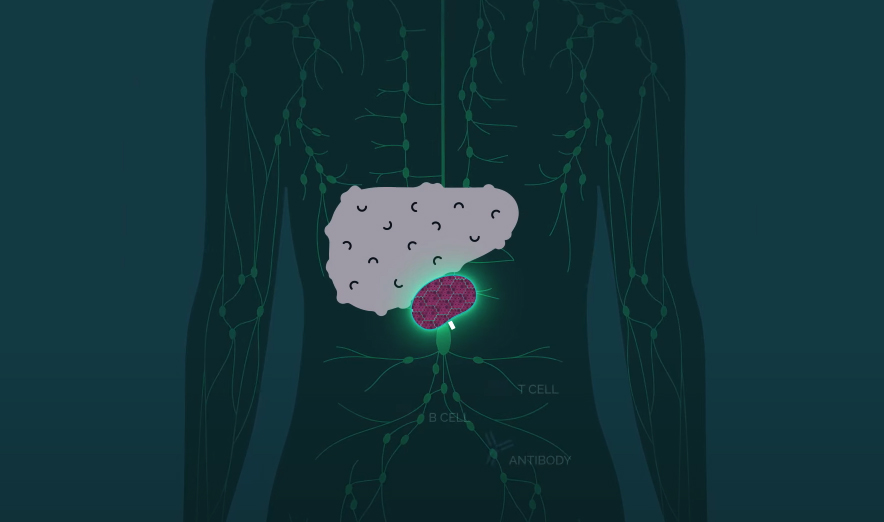

Their treatment starts with the isolation of hepatocytes — the cells that make up 80% of our liver mass — from a donated liver. The cells are then injected into lymph nodes — these tiny glands produce immune system cells to help us fight infections, and we have hundreds of them.

From their new home inside the lymph nodes, the injected hepatocytes receive the liver’s distress signals and begin multiplying until the body’s natural regulator puts a stop to the growth.

“Over time, the lymph node disappears entirely, and what you’re left with is a highly vascularized miniature liver that is supporting the function of the native liver by helping to filter the animal’s blood supply,” LyGenesis CEO Michael Hufford told MIT Technology Review.

To the clinic

In December 2020, LyGenesis received FDA clearance to test the treatment in a phase 2A clinical trial, which is now expected to kick off at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston within the next few weeks.

The trial will involve 12 adults with end-stage liver disease who are not eligible for liver transplants, and its goal will be to test the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of LyGenesis’ treatment in humans for the first time.

Four of the trial participants could end up with five new mini livers.

The first person in the trial will have a dose containing 50 million hepatocytes injected into a lymph node near their liver via an outpatient endoscopic surgery, which is much less invasive and risky than the standard liver transplant operation.

After waiting a week to check for potential problems, the researchers will move on to perform the same procedure in three more trial participants.

After that, four participants will receive injections of 150 million hepatocytes spread out equally across three lymph nodes, and the final four people will receive injections of 250 million cells across five lymph nodes — potentially resulting in five new mini livers.

Looking ahead

In their pig studies, the researchers injected a minimum of 360 million cells into three of the animals’ lymph nodes, but LyGenesis CSO Eric Lagasse expects even the lowest dose to be effective in the upcoming clinical trial.

“My view is that one cell would be enough,” he told MIT Tech Review. “If you leave enough time, that cell will expand, grow, and multiply, and eventually generate an ectopic liver.”

Even if millions of cells are used, a single donor liver has enough hepatocytes to treat 75 or more people. Donor livers that aren’t healthy enough for transplantation can be a source of hepatocytes, too — the cells for the trial will be coming from a rejected organ.

“Using these organs that are otherwise discarded to help patients … is revolutionary,” Valerie Gouon-Evans, a liver regeneration expert not involved with the trial or LyGenesis, told MIT Tech Review.

Donor livers that aren’t healthy enough for transplantation can be a source of hepatocytes, too.

The researchers will follow up with trial participants for at least a year and expect to have the entire trial wrapped up in under two years. There is a chance the participants’ bodies will reject the injected cells, just like liver transplants, so they’ll need to take immunosuppressants.

However, that might not always be the case — LyGenesis recently announced a research partnership with regenerative medicine company iTolerance to develop tech that would eliminate the need for the drugs following LyGenesis’ liver treatment.

If they can succeed at that, LyGenesis might not only be able to end the liver shortage, but also give recipients the ability to enjoy their mini livers and fully functional immune systems.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].