For the first time, researchers have used drone photography to identify pregnant dolphins, giving conservationists a new way to monitor the health of dolphin populations.

The challenge: Researchers from University of Aberdeen have been monitoring the bottlenose dolphins that live off the Scottish coast, in the Moray Firth Special Area of Conservation, for more than 30 years.

During that time, if they saw a female dolphin with a new calf, they would know she had been pregnant, but they didn’t have a way to tell if a dolphin was pregnant. That meant they never knew how many pregnancies ended in failure or how many calves died young.

“We know that reproductive failure has been linked to harsh environmental conditions.”

Barbara Cheney

“Data on failed pregnancies could provide information on how healthy a particular dolphin is as well as helping to identify the causes of changes in the population,” researcher Barbara Cheney said in a press release.

“We know that reproductive failure has been linked to harsh environmental conditions, pollution, and naturally occurring toxins, but previously we have only been able to estimate the impact in populations where animals are easy to capture or remotely sample,” she continued.

Help from above: Other research has found that it’s possible to identify pregnant whales using drone photography, so the Aberdeen researchers teamed up with scientists from Duke University to see if they could do it for pregnant dolphins.

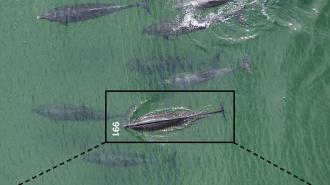

In July and August 2017, they went out on boats five times to gather aerial images of the dolphin population using unmanned drones. They identified 64 dolphins in the photos and analyzed the widths of the animals to predict which ones were pregnant.

The researchers were later able to confirm the pregnancy status of 15 of the females at the time of the drone survey and found that their predictions had been right for 14 of the 15 (they’d missed one pregnant dolphin).

The big picture: The study of pregnant dolphins isn’t the only recent example of drones aiding conservation efforts — drones are being used to track bison, collect whale snot, protect elephants from poachers, and more.

“That’s a 1,000-pound animal with a lot of teeth. If you can measure from the air, it’s a lot better.”

Wayne Perryman

In many instances, the use of drones is less invasive for the animals than a traditional technique — counting animals in aerial photographs can mean they don’t have to be fitted with tracking devices, for example.

It can be a lot safer for conservationists, too — prior to switching to drone photography, researchers from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) used to measure Antarctic leopard seals by hand, after manually tranquilizing them.

“That’s a 1,000-pound animal with a lot of teeth,” NOAA biologist Wayne Perryman told the National Wildlife Federation in 2019. “If you can measure from the air, it’s a lot better.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].