Hundreds of long-lost Maya and Olmec ceremonial sites were recently uncovered in southern Mexico — all thanks to lidar data.

By using the lidar to map large areas of densely forested land, archeologists are finding structures that were previously invisible — and changing our understanding of previous civilizations.

What is lidar? Lidar (“Light Detection and Ranging”) is a technology that can be used to create 3D maps of objects or environments. It works by hitting the target with pulses of laser light and then measuring how long it takes the light to reflect back to the receiver.

Lidar has been around for decades, and its applications include mapping Martian clouds, helping autonomous cars “see” the world, and combating global warming in cities.

Lidar data is also helping archaeologists identify ancient structures.

Lidar archaeology: Many sites that once played an important role in past civilizations are now covered by dense vegetation, which makes them impossible to see from planes using standard cameras.

However, because some of these structures are so large, they aren’t identifiable from the ground, either — you need a bird’s eye view to know they exist.

By using drones and planes to collect lidar data, archaeologists can create 3D maps of large areas of Earth covered by vegetation, and this ability is yielding major historical discoveries.

“This site was not known because it is so flat and huge … with lidar, it pops up as a very well-planned shape.”

Takeshi Inomata

The background: In 2017, the Mexican government provided an international team of archaeologists with a low-res lidar map of more than 30,000 square miles of Mesoamerica (the part of the world the Olmecs, Aztecs, and several other early civilizations occupied).

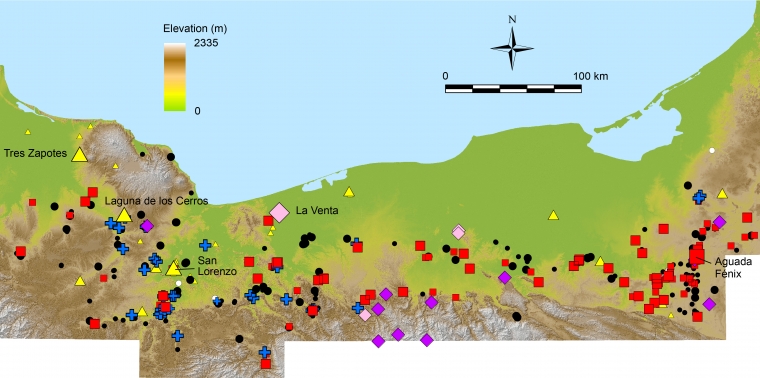

The team noticed what looked to be a massive structure hidden in the data. It then used higher-res lidar tech to map the area of intrigue and discovered what is now the largest-known Mayan ceremonial site: Aguada Fénix.

“[T]his site was not known because it is so flat and huge — it just looks like a natural landscape,” lead researcher Takeshi Inomata at the University of Arizona explained. “But with lidar, it pops up as a very well-planned shape.”

In the future, AIs trained to identify notable features in lidar data could help archaeologists spot them.

What’s new: Using that same survey data, the group has now discovered nearly 500 smaller but similar ceremonial sites that were likely built about 1,000 years before the Mayans’ heyday, in an area including the Olmec region and the western Maya lowlands.

They also discovered a new plaza at a known Olmec ceremonial site (San Lorenzo) that’s older, but similar in shape and orientation to Aguada Fénix. This similarity suggests that the Mayans were influenced by earlier civilizations and didn’t develop wholly independently — answering a question that has long puzzled archaeologists.

“There has always been debate over whether Olmec civilization led to the development of the Maya civilization or if the Maya developed independently,” Inomata said in 2020. “So, our study focuses on a key area between the two.”

This discovery points to the idea that early Olmec construction served a blueprint for the Mayans.

“If the Olmec were building ritual centers with rectangular, platform-lined plazas pointed at sunrise on important days at least 300 years before the Maya did so, then the Maya may have inherited those concepts (and probably their religious underpinnings) from the Olmec,” Inomata told Ars Technica.

Bring on the AI: Inomata’s team is far from alone in taking advantage of lidar tech for archaeological purposes.

A U.K. project recently spotted 120 new archaeological features hidden on an English estate, including ones more than 4,000 years old. In the U.S., researchers have been able to piece together colonial life in New England from lidar data, identifying abandoned farms, roads, and more.

In the future, it might be even easier for archaeologists to identify notable features in lidar data thanks to AIs trained to spot them.

“This saved the equivalent of years of manual labor.”

Dylan Davis

One such AI, developed at Penn State, can spot earth mounds in lidar data — these mounds were created by indiginous North American populations and can help us understand how those populations lived, what they ate, and how they interacted with each other.

“The process resulted in several thousand possible features that my colleagues and I checked by hand,” researcher Dylan Davis told Singularity Hub. “While not entirely automated, this saved the equivalent of years of manual labor that would have been required for analyzing the whole lidar image by hand.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].