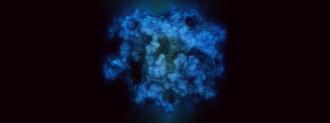

It’s been dubbed “cancer’s Death Star”: a deadly, round protein with a maddeningly smooth surface, where drugs could not stick — a Death Star, but without a trench and exhaust port.

“It’s spherical and impenetrable. Proteins usually have nooks and crannies which you use to latch on to. This was a huge challenge for chemists because drugs would essentially bounce off,” David Reese, executive vice president for research and development at biotech Amgen, told The Guardian’s David Cox.

But new drugs may finally be able to target this mutated protein — which causes cells to replicate out of control, forming tumors — and they could be approved as soon as this year, Cox writes in a detailed feature.

The Undruggable Mutation

The that’s-no-moon protein is called KRAS, and a KRAS mutation can be found in up to 96% of pancreatic cancers and a shade over 50% of colorectal cancers, Cox reports.

Part of a family of proteins called RAS, these proteins work like a growth on/off switch, rapidly flexing and relaxing the protein’s shape.

But when a KRAS mutation jams the protein into the “on” position, the cells grow out of control, forming cancerous tumors.

“Mutations in the gene KRAS are the most frequent drivers of tumour development across the spectrum of human cancers,” Roy S. Herbst and Joseph Schlessinger, of the Yale Cancer Center and Department of Pharmacology at Yale School of Medicine, respectively, wrote in Nature.

This is why they’re dangerous, but it also makes them attractive targets.

The battle against KRAS mutation and the other problematic RAS proteins is one of desperation and excitement, Cox explains. By the 1980s, researchers were already at their wit’s end while searching for “oncogenes” — the genetic switches for tumor creation.

After almost a decade of searching, the highly-sought oncogene was close to being considered a dead end, when Channing Der, then at Harvard Medical School, flipped the field on its head. Der had been assigned to test 20 different oncogene candidates.

“People thought it wasn’t going to work,” Der told Cox. “I began, and certainly for five months, the chances of success seemed to be pretty slim. I was ready to just wrap this up, and move on to something else that might be more productive, when I made the discovery which changed the course of my professional career.”

Der had discovered the RAS proteins. Gary Cooper, whose lab Der was working in, told him it “could be one of the most significant discoveries in cancer biology in decades.”

Researchers and pharma companies sprang into action, looking for ways to target the mutated proteins, with the KRAS mutation top of the list. But they were met with failure after failure, drugs bouncing off the protein’s smooth surface.

The KRAS mutation earned a reputation as “undruggable.”

A Crack in the Surface

Recently, a particular KRAS mutation (called G12C) once again inspired hope.

In 2013, a group led by UC San Francisco chemist Kevan Shokat found a drug that could sit in a minuscule indent in the protein’s surface — a proton torpedo that just fit the Death Star’s thermal exhaust port.

“The drug was sitting in a beautiful pocket that no one had ever seen on the protein,” Shokat said.

Pharmaceutical companies leapt back into the fray, targeting KRAS mutation G12C, which is found in 13% of patients with the most common form of lung cancer and 3% of patients with colorectal cancer.

“A lot of us started thinking, maybe this groove in G12C is like a little hook that a mountain climber would use, somewhere to put your fingertips, and grasp on to,” Amgen’s Reese told Cox.

In 2019, those efforts began to reap rewards. Multiple research groups, including Amgen, reported promising results for new drugs targeting the mutation.

Amgen’s drug, dubbed sotorasib, eliminated tumors in mice, and shrunk them in a handful of lung cancer patients. Tumors shrank in two of the four patients after six weeks of treatment, Science reported, and when the trial was expanded to 13 patients, that roughly half number held.

A second drug company, Mirati, also reported tumor shrinking in three of six lung cancer patients and one in four colorectal cancer patients with their own KRAS mutation-targeting drug. Der is a consultant for Mirati.

The Glimmer of a New Hope

From those small numbers have risen some big hopes. Late in January 2021, Amgen announced the results of a larger phase 2 trial which tested sotorasib in 126 patients with advanced lung cancer and the G12C mutation. In that study, 81% of the patients’ cancers stabilized and 37% had tumor shrinkage.

“If the tumour mass is too large, you can’t operate,” Der told Cox. “If you can shrink the tumour, that patient might now be a candidate for surgery, and at the end of the day, our best treatment for cancer is still surgical resection of the tumour. That is what cures people.”

KRAS mutation-targeting drugs aren’t a silver bullet; only some patients suffer from this G12C KRAS mutation, and cancer is well-known for developing resistance to treatments.

Even still, in a field that’s been frustrated for so long, “a glimmer of hope is great,” Der told Science.

Amgen has put sotorasib up for review by the FDA and European Medicines Agency, Cox reports; there is now hope that the drug could be approved before the year’s end.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].