Speech is unique to humans, but we still know very little about its evolutionary origins. According to one long-standing theory, movement of the larynx down into the throat allowed the vocal tract to produce a wider range of sounds; yet, some monkey species can produce human-like vowels without this anatomical feature, while others that do have it cannot. And although researchers have identified variations in language-related genes, it has proven difficult to link these genetic changes to the emergence of speech in our hominin ancestors. Additionally, brain structures and connections thought to be crucial for speech and language are present in nonhuman primates.

A unique part of the human brain

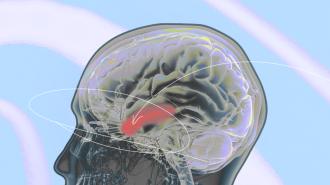

Researchers in France have now identified a unique feature of human brain anatomy that may help to explain how speech emerged. Their work, published in the journal Communications Biology, suggests that our ability to produce such complex vocalizations might be due to subtle modifications of a brain structure we share with other primates.

Many of the brain structures involved in language and speech production are found in the frontal cortex. Céline Amiez of the University of Lyon and her colleagues have previously shown that much of this brain region is organized similarly in Old World monkeys such as baboons and macaques as well as in humans and other nonhuman primates.

One region in particular, the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (vlPFC), varies widely between species. Amiez and her colleagues examined neuroimaging data from 80 human, 225 chimp, 80 baboon, and 80 macaque brains. Their main finding is that a structure called the prefrontal extent of the frontal operculum (PFOp), which is located within the vlPFC and is fully developed in humans, is only partially developed in chimps and appears to be completely absent in Old World monkeys.

Importantly, they also found significant variation in the organization of this structure between individual chimpanzee brains, with those having the most human-like PFOp, particularly in the left hemisphere, having greater voluntary control over their larynx and facial muscles.

Evolution of speech

Recent paleontological studies show that smaller-brained Homo species, but not earlier hominins such as Australopithecines, likely had a human-like PFOp, suggesting that the structure arose at some point after the emergence of the Homo genus more than two million years ago, rather than during the brain expansion seen in modern humans and Neanderthals, which occurred between 400,000 and 800,000 years ago. Altogether, this supports the view that the PFOp is a recently evolved brain structure that might be limited to Homo species and is associated with the motor control needed to produce complex speech.

In humans, the PFOp is found next to Broca’s area, a critical component of the brain’s speech network. The study authors say that it may “optimize the anatomo-functional relationships” between Broca’s area and temporal lobe regions involved in processing auditory information, and may also play a role in the manipulation of cognitive representations required for speech.

This article was reprinted with permission of Big Think, where it was originally published.