Affecting an estimated 50 million people globally, epilepsy is one of humanity’s most common neurological disorders — and one of its longest chronicled: written records of its unprovoked seizures date back centuries.

Fittingly for such an old foe, there are numerous ways to treat epilepsy, from deep brain stimulation to diet and anti-epileptic drugs. For the roughly one-third of epilepsy patients for whom drugs do not work, surgery can be a viable alternative — a “huge game changer,” Aswin Chari, a neurosurgeon at University College London, told Nature’s Miryam Naddaf.

In these surgeries, surgeons try to remove the region of the brain causing the seizures — known as the epileptogenic zone. For fairly obvious reasons, making sure that what they believe is the epileptogenic zone is correct is an important — and difficult — part of the task.

To help surgeons accurately locate the zone, researchers are developing a “digital twin” of the brain that can model potential patients and even simulate surgical results.

For the roughly one-third of epilepsy patients for whom drugs do not work, surgery to remove the part of the brain the seizures originate from can be a viable alternative.

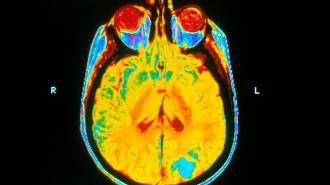

Cut it out: To determine where the epileptogenic zone is before going beneath the skull, researchers use brain imaging methods like MRIs, EEGs, and stereoelectroencephalography (SEEG), which uses implanted electrodes to measure brain activity, Naddaf reported.

But SEEG only captures brain currents that occur at high frequencies, however, and low-frequency activity can occur in 20% of seizures. “A lot of people with epilepsy don’t have visible problems on the scan,” Amsterdam University Medical Centre neuroscientist Linda Douw told Naddaf.

The surgeries only have a 50% success rate, a problem chalked up in part to not identifying the actual epileptogenic zone.

A digital brain: To improve the outcome of the surgery, researchers from France’s Aix-Marseille Université developed the Virtual Epileptic Patient (VEP) atlas.

VEP “uses personalized brain models and machine learning methods to estimate [epileptogenic zones] and to aid surgical strategies,” the authors wrote in their paper for Science Translational Medicine.

The VEP is something of a “digital twin,” an advanced model made using information plucked from the real thing. These can be used to digitize manufacturing processes, supply chains, or even entire planets, which can then be used to analyze systems, run simulations, and plan for and predict various outcomes.

One team of researchers at the University of Illinois-Chicago’s Surgical Innovation Training Laboratory are attempting to create something similar, creating digital models of surgical sites so that surgeons do not need to go in blind.

However, the surgery only has a 50% success rate, a problem chalked up in part to not identifying the actual proper part of the brain.

Like the Chicago work, VEP is an ambitious and AI-enhanced version of personalized medicine.

To create a patient’s VEP, the team feeds MRI, EEG, and SEEG data to a virtual network based on the brain, molding it to resemble the patient’s own. Using AI simulation data, the team can then mimic brain activity in their digital model, then isolate the likely epileptogenic zone. They can also simulate the effects of surgery at specific sites in the brain to dial in the proper piece of the brain to remove.

VEP currently can simulate down to one square millimeter, Naddaf reported, although the researchers are looking to make it 1,000 times sharper.

Putting VEP to the test: VEP is currently being put to the test in a clinical trial to determine if it helps improve the outcome of epilepsy surgeries. Called EPINOV, it has enrolled 365 patients across 11 different French hospitals since kicking off in June 2019, Naddaf reported.

The study will look to compare the outcome of the surgery via frequency of seizures at the one-year mark in patients whose surgeries were informed by VEP data versus a control group, as well as VEP’s influence on surgical strategies and morbidity rates.

After the surgeries are completed, VEP simulations will be run for the control group as well to compare the actions of the actual surgeons with VEPs suggestions.

“The outcome after a year is a pretty good indicator for how things are going to be in the longer run,” UCL neurologist John Duncan told Naddaf, although he noted that “you have to expect that some of those people who are seizure-free for a year will not still be seizure-free at five years.”

To improve the outcome of the surgery, researchers from France’s Aix-Marseille Université developed a personalized, digital model of a brain.

Challenges and next steps: The researchers know that their model has limitations, including the shifting patterns of seizures and the epileptogenic zones possibly being in places that cannot be captured with SEEG.

VEP may also suggest operating on a larger part of the brain than surgeons may be comfortable with, Duncan told Naddaf; proving the model is clinically beneficial will be the team’s great challenge.

If VEP proves successful, the researchers hope a similar technique can then be used to model other neurological disorders.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].