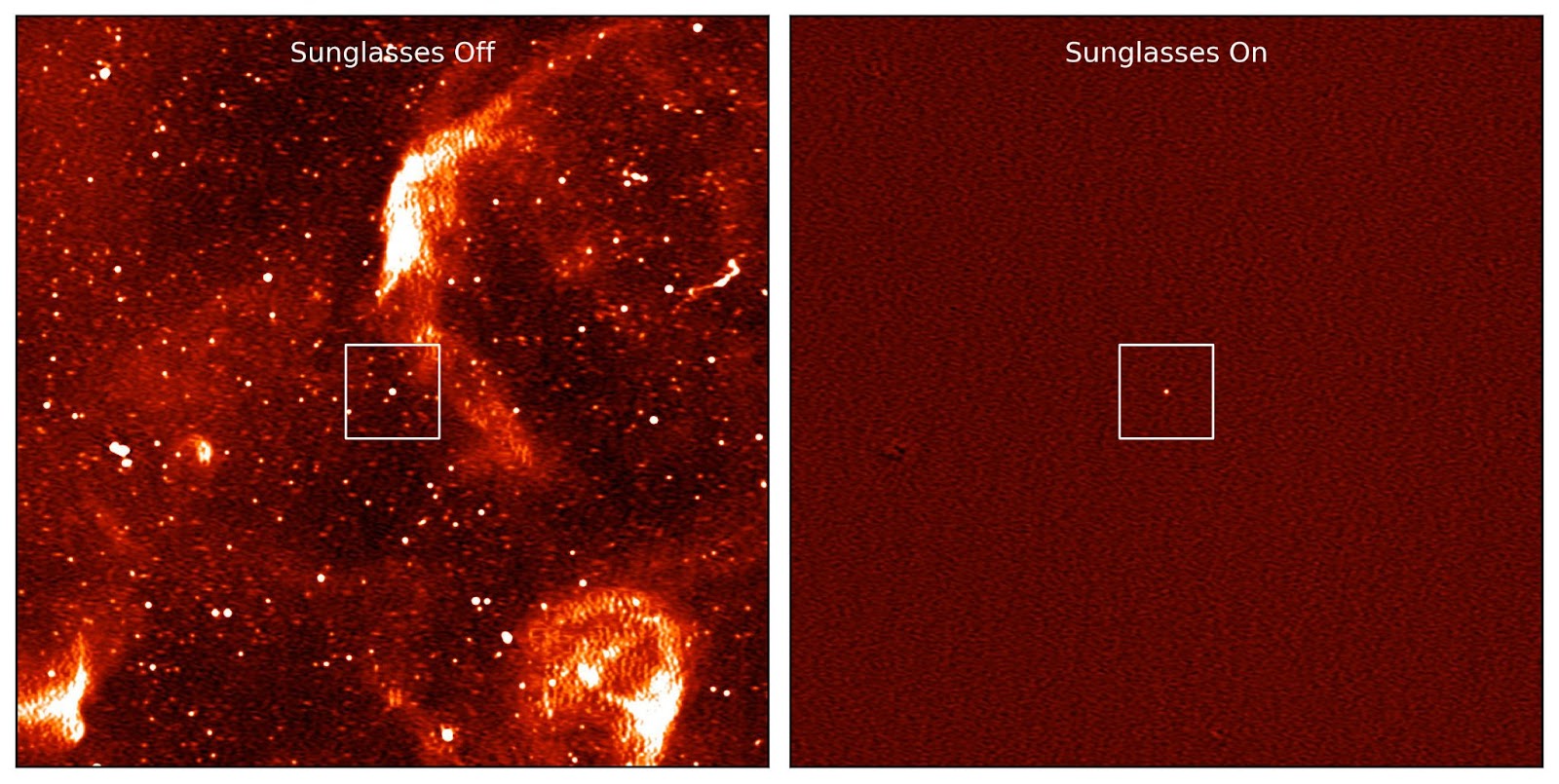

Australian astronomers discovered the brightest pulsar ever seen outside the Milky Way — by putting “sunglasses” on a telescope.

The spinning stars: At the end of their lives, some massive stars collapse into super-dense neutron stars, and some of those neutron stars spin incredibly fast while emitting two beams of light in opposite directions, like a lighthouse — those are pulsars.

If a pulsar’s beams of light cross our line of sight, the star appears to flicker. Astronomers can look for evidence of that flickering in telescope data, but if the pulsar is unusual — e.g., it’s spinning faster than normal or has a particularly wide light beam — it can go undetected.

“I didn’t expect to find a new pulsar, let alone the brightest.”

Yuanming Wang

Polarizing idea: A team led by University of Sydney astronomer Tara Murphy took a different approach to pulsar hunting, focusing instead on the ability of some pulsars to “polarize” light.

Light travels in waves, and in its natural state, it’s “unpolarized,” meaning the waves move randomly in three dimensions (up and down, left and right).

However, light can become “polarized” — its waves then move in just two dimensions along a single plane. Something as simple as reflecting off water can polarize light, and the strong magnetic field of a pulsar can polarize it, too.

“Extreme pulsars are one of the missing pieces in the vast picture of the pulsar population.”

Yuanming Wang, David Kaplan, and Tara Murphy

Stellar sunglasses: Polarized sunglasses help us see by blocking any light that isn’t vertically polarized (including the horizontally polarized light we perceive as glare), and Australia’s ASKAP radio telescope has its own “sunglasses” that allow it to capture only polarized light.

Using that feature, Murphy’s team was able to spot a pulsar that had previously escaped detection due to its wide light beam. They then confirmed the pulsar using the MeerKAT radio telescope in South Africa.

This pulsar — PSR J0523-7125 — is located within the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC). That’s the only galaxy other than the Milky Way in which we’ve spotted pulsars, and this one is more than 10 times brighter than any other seen in the LMC.

“This was an amazing surprise,” said lead author Yuanming Wang. “I didn’t expect to find a new pulsar, let alone the brightest. But with the new telescopes we now have access to, like ASKAP and its sunglasses, it really is possible.”

The big picture: To truly understand pulsars, we need to study all kinds of them, including the “weird” ones that escape our traditional detection techniques — and this study demonstrates how we can find them.

“Extreme pulsars are one of the missing pieces in the vast picture of the pulsar population … This discovery is just the beginning,” the discoverers of the new pulsar wrote in the Conversation.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].