Researchers at UC Riverside have developed a light-powered soft robot that can swim along the water’s surface, powered by sunlight.

They envision their robotic strip as eventually being able to sop up oil and other contaminants, cruising around perpetually and keeping things clean — especially useful for pollution spills in remote locations where sending ships and human crews is costly and difficult.

“Our motivation was to make soft robots sustainable and able to adapt on their own to changes in the environment,” UCR chemist and study author Zhiwei Li said.

The robot was inspired by steam engines and animals who make their living walking on the films created by water’s surface tension.

What it does: The robot was inspired by old-fashioned steam engines and a group of animals, called neustons, who make their living walking on the films created by water’s surface tension. Their creation, published in Science Robotics, was dubbed Neusbot in their honor.

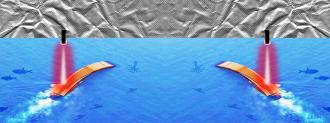

The minuscule prototype robot — 20mm long and 5mm wide, New Atlas reported — looks a little like a stick of chewing gum or a ribbon. The soft robot cruises along the water’s surface using a pulsing motion driven by light, an artificial version of the same trick used by neustons like the water strider.

While previous soft robots had already got that bending motion down, Neusbot’s ability to make adjustable, oscillating motions is new, and it’s the key to controlling where the soft robot goes.

Steam power: The power for Neusbot’s motion lies in its layers.

“There aren’t many methods to achieve this controllable movement using light. We solved the problem with a tri-layer film that behaves like a steam engine,” Li said.

Well, not a steam engine like you’re envisioning: coal shovels, smoke stacks, pistons pumping. But the principle is still the same: the energy generated by boiling water — steam — provides the robot’s energy.

The soft robot has three layers. The top and bottom ones are hydrophobic, meaning they just hate water on a molecular level, which keeps Neusbot afloat.

The middle layer is the engine room. This layer is porous, letting in and holding water. It also contains tiny little structures of iron oxide and copper, called nanorods. When all of those things are exposed to white light — like sunlight — they undergo a chemical reaction, generating heat.

The water in the middle layer turns into steam, generating tiny bubbles which then causes the layers to move, Optica explains. This movement brings in more water, keeping the engine going.

“Our motivation was to make soft robots sustainable and able to adapt on their own to changes in the environment,” Li said. “If sunlight is used for power, this machine is sustainable, and won’t require additional energy sources.”

According to Optica, Neusbot currently moves at about four body lengths per minute. The researchers found that they could adjust the direction it moved in by changing the angle of the light source. (But powered only by the sun, the soft robot would always move in one direction, a challenge to overcome if Neusbot is going to be useful in real-world conditions.)

Soft robot, hard problem: The UC Riverside team sees Neusbot as a potential robotic sponge, moseying around and removing pollution from drinking water and mopping up the remnants of oil spills.

While their current model is only three layers, the team wants to test adding a fourth layer to the soft robot that could absorb oil or other chemicals. Armed with its sponge layer, a flotilla of Neusbots could then be turned loose on oily water, powered by the sun. Li sees them as being especially advantageous for spills in remote, difficult-to-access areas.

Li is already confident in Neusbot’s ability to survive the salty marine environment.

“Normally, people send ships to the scene of an oil spill to clean by hand. Neusbot could do this work like a robot vacuum, but on the water’s surface.”

zhiwei li

“Normally, people send ships to the scene of an oil spill to clean by hand. Neusbot could do this work like a robot vacuum, but on the water’s surface,” Li said.

They are also attempting to make Neusbot capable of ever-more-complex motions.

“We want to demonstrate these robots can do many things that previous versions have not achieved.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].