This article is an installment of Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Thursday morning by subscribing here.

A machine for making oxygen on the moon is heading to space.

The European Space Agency (ESA) is building the device to test whether astronauts can tap into the wealth of oxygen trapped in the lunar regolith (the layer of dust and rock covering the moon’s surface).

The device is expected to reach the moon by 2025, and if it works as hoped, the agency plans to scale-up the tech, building an oxygen-producing plant on the moon in the 2030s.

Besides letting humans breathe, it could also help make fuel for spacecraft.

Why it matters: ESA hopes to land its first astronauts on the moon before the end of the 2030s, and its goal is to establish a long-term presence on the lunar surface.

“If we want to really explore the moon, we need to be there for weeks and months at a time.”

David Parker

This could lead to major scientific breakthroughs, the kind that change our understanding of the universe and our place in it. It could also prepare humanity for crewed missions to Mars and beyond, leading to even more groundbreaking discoveries.

“[The moon is] a museum of 4.5 billion years of solar system history … with material coming from the sun but also interplanetary space,” David Parker, ESA’s director of human and robotic exploration, said in 2019.

“With the Apollo missions, we only basically went to the museum gift shop, grabbed a few things and came back again, and then abandoned it for 50 years … If we want to really explore the moon, we need to be there for weeks and months at a time,” he continued.

Living off the (lunar) land: Astronauts are tough, but even they can’t do without food, water, and oxygen, so we’ll need to make sure they have plenty while on the moon — plus enough fuel for the return mission.

Trapped in the lunar regolith is enough oxygen to theoretically sustain 8 billion people for more than 100,000 years.

Sending those resources from Earth to the moon would be incredibly expensive, though, as every extra ounce of payload on a rocket increases its cost.

Thankfully — despite its lack of life, liquid water, or an atmosphere — the moon already has some of what astronauts need to survive. By exploiting those local resources, we could cut the cost of space exploration.

The problem is that accessing the resources isn’t going to be easy. There’s theoretically enough oxygen on the moon to sustain 8 billion people for more than 100,000 years, but it’s trapped inside the lunar regolith.

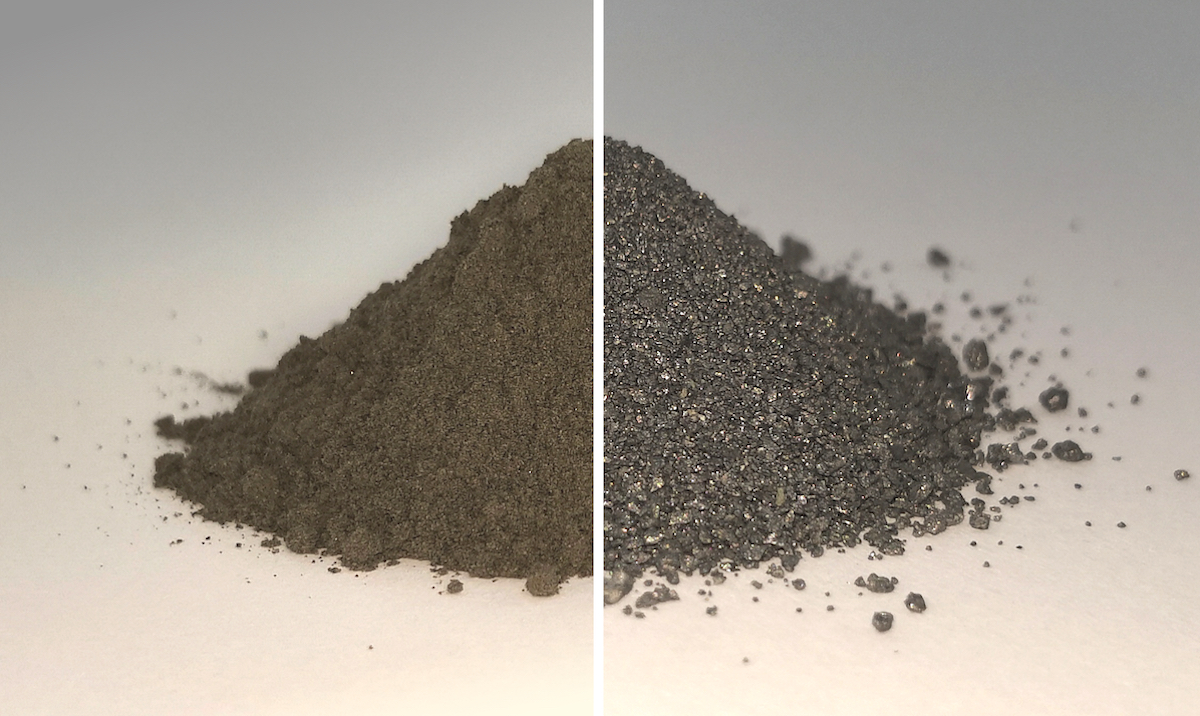

The idea: In 2019, researchers demonstrated that they could extract oxygen from simulated lunar regolith here on Earth.

The technique involves placing the regolith in a container with molten salt and then passing an electric current through it. Besides freeing oxygen from its chemical bonds, the process extracts useful metal alloys, which could be used by astronauts for building materials.

Getting a technology to work in a lab is a lot easier than doing it on the moon, though, so in 2021, ESA challenged several groups to design a solar-powered, oxygen-extracting device it could send to the moon by 2025 as part of a demonstration mission.

The prototype “will need a method of acquiring the samples from the surface quickly, transferring them to a preparation area, before finally loading the reactor which grabs the oxygen,” said David Binns, a systems engineer at ESA’s Concurrent Design Facility, “and at each step of the way we need to measure and analyze what happens on the moon.”

The device also had to be compact, low power, and capable of extracting 50 to 100 grams of oxygen from regolith (about 70% of what’s available) within 10 days — that’s to ensure the process could be completed during one 14-day period of daylight on the moon.

“Being able to extract oxygen from moonrock, along with usable metals, will be a game changer for lunar exploration.”

David Binns

Looking up: ESA has now chosen a machine designed by a team with Thales Alenia Space at its helm for the demonstration mission and will now work with the group to build the device.

If the prototype works as hoped during the demo, ESA plans to build a larger version on the moon in the 2030s. This plant will produce oxygen for astronauts to breathe and for rocket fuel.

“Being able to extract oxygen from moonrock, along with usable metals, will be a game changer for lunar exploration, allowing the international explorers set to return to the moon to ‘live off the land’ without being dependent on long and expensive terrestrial supply lines,” said Binns.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].