An international team of researchers has reconstructed the life of a woolly mammoth that lived in Alaska more than 17,000 years ago.

By deciphering clues hidden in his tusk, we may not only unravel the mysterious life and death of these charismatic creatures, but also understand the impact of climate change on modern species.

Why mammoths went extinct is a mystery — theories include disease and a changing climate.

Mammoth undertaking: Woolly mammoths were large, elephant-like creatures that roamed the Earth for nearly five million years, before going extinct around 2000 B.C.

Exactly why the species went extinct is a mystery — theories include disease, overhunting by humans, changing climate, or some combination of factors — and solving it has been challenging because we don’t know much about how the animals lived.

Why it matters: If climate did contribute to the woolly mammoth’s demise, studying their experience might help us predict how modern species will respond to today’s warming world.

“The Arctic is seeing a lot of changes now, and we can use the past to see how the future may play out for species today and in the future,” senior author Matthew Wooller said in a press release.

“Trying to solve this detective story is an example of how our planet and ecosystems react in the face of environmental change,” he continued.

“From the moment they’re born until the day they die, they’ve got a diary … written in their tusks.”

Pat Druckenmiller

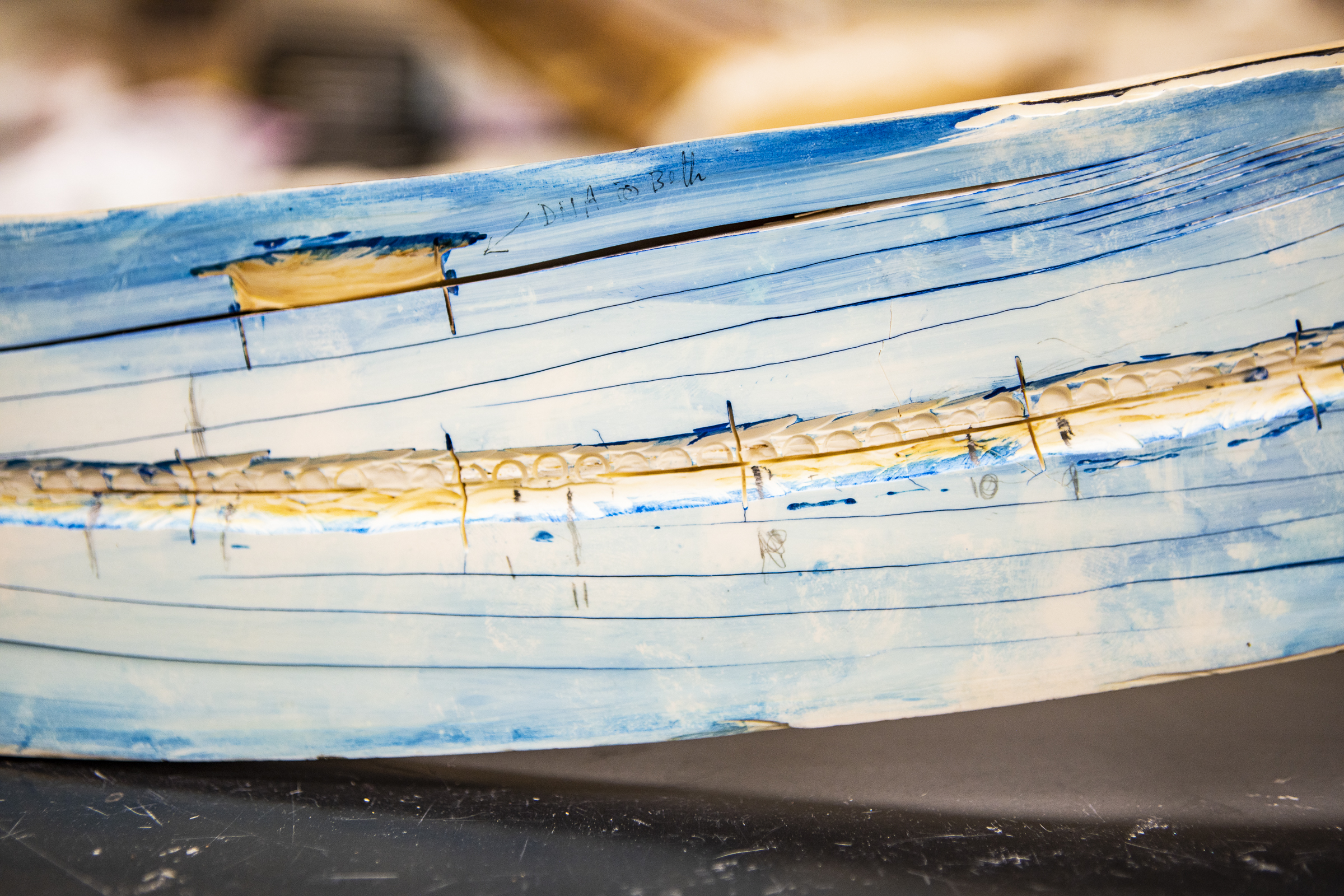

All in the tusk: When a woolly mammoth is born, its tusk is just a tiny cone, and as it ages, new layers are stacked on top of that cone. Looking at those layers can offer clues into a mammoth’s life, similar to how we can learn about a tree’s environment by studying the rings in its trunk.

“From the moment they’re born until the day they die, they’ve got a diary and it’s written in their tusks,” co-author Pat Druckenmiller said. “Mother Nature doesn’t usually offer up such convenient and life-long records of an individual’s life.”

For this new study, the researchers sliced an 8-foot-long woolly mammoth tusk lengthwise and analyzed the chemical signatures trapped in each layer.

They then connected those signatures to different places and events to piece together the story of the mammoth’s life.

The woolly mammoth walked an estimated 44,000 miles during its 28-year life.

A spike in nitrogen in one of the last bands to form on the mammoth tusk, for example, likely indicates that the animal died of starvation. The food it ate, meanwhile, left signatures that could be connected to specific parts of the Alaskan landscape.

Using that information, the researchers were able to trace the mammoth’s movements and determine that it walked an estimated 44,000 miles during its 28-year life — if that had been in a straight line, it could’ve almost circled the Earth twice.

Historic study: One woolly mammoth tusk isn’t enough to explain the extinction of an entire species, let alone predict future extinctions, but it does give scientists new insights into the daily life of the enigmatic creatures.

“This is a better understanding [of] how they behaved, what environment they used,” Wooller told the New York Times.

“When you’re trying to figure out what the causes of an extinction were,” he added, “you need to know a little bit more about the behavior and ecology of the organisms involved.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].