Where did all this come from? In every direction we care to observe, we find stars, galaxies, clouds of gas and dust, tenuous plasmas, and radiation spanning the gamut of wavelengths: from radio to infrared to visible light to gamma rays. No matter where or how we look at the universe, it’s full of matter and energy absolutely everywhere and at all times. And yet, it’s only natural to assume that it all came from somewhere. If you want to know the answer to the biggest question of all — the question of our cosmic origins — you have to pose the question to the universe itself, and listen to what it tells you.

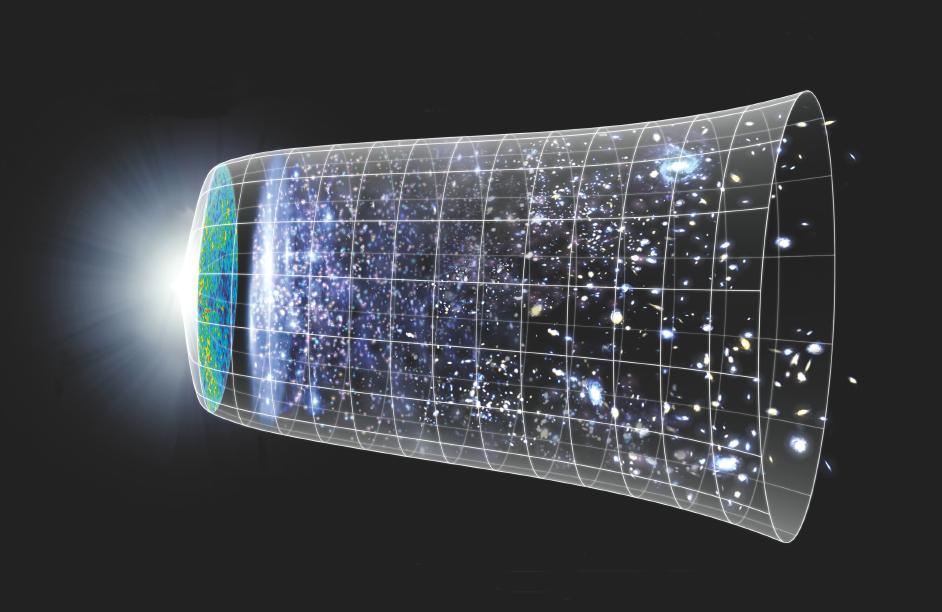

Today, the universe as we see it is expanding, rarifying (getting less dense), and cooling. Although it’s tempting to simply extrapolate forward in time, when things will be even larger, less dense, and cooler, the laws of physics allow us to extrapolate backward just as easily. Long ago, the universe was smaller, denser, and hotter. How far back can we take this extrapolation? Mathematically, it’s tempting to go as far as possible: all the way back to infinitesimal sizes and infinite densities and temperatures, or what we know as a singularity. This idea, of a singular beginning to space, time, and the universe, was long known as the Big Bang.

But physically, when we looked closely enough, we found that the universe told a different story. Here’s how we know the Big Bang isn’t the beginning of the universe anymore.

Theoretical roots of big bang

Like most stories in science, the origin of the Big Bang has its roots in both theoretical and experimental/observational realms. On the theory side, Einstein put forth his general theory of relativity in 1915: a novel theory of gravity that sought to overthrow Newton’s theory of universal gravitation. Although Einstein’s theory was far more intricate and complicated, it wasn’t long before the first exact solutions were found.

- In 1916, Karl Schwarzschild found the solution for a pointlike mass, which describes a nonrotating black hole.

- In 1917, Willem de Sitter found the solution for an empty universe with a cosmological constant, which describes an exponentially expanding universe.

- From 1916 to 1921, the Reissner-Nordström solution, found independently by four researchers, described the spacetime for a charged, spherically symmetric mass.

- In 1921, Edward Kasner found a solution that described a matter-and-radiation-free universe that’s anisotropic: different in different directions.

- In 1922, Alexander Friedmann discovered the solution for an isotropic (same in all directions) and homogeneous (same at all locations) universe, where any and all types of energy, including matter and radiation, were present.

That last one was very compelling for two reasons. One is that it appeared to describe our universe on the largest scales, where things appear similar, on average, everywhere and in all directions. And two, if you solved the governing equations for this solution — the Friedmann equations — you’d find that the universe it describes cannot be static, but must either expand or contract.

This idea, of a singular beginning to space, time, and the universe, was long known as the Big Bang. But physically, when we looked closely enough, we found that the universe told a different story.

This latter fact was recognized by many, including Einstein, but it wasn’t taken particularly seriously until the observational evidence began to support it. In the 1910s, astronomer Vesto Slipher started observing certain nebulae, which some argued might be galaxies outside of our Milky Way, and found that they were moving fast: far faster than any other objects within our galaxy. Moreover, the majority of them were moving away from us, with fainter, smaller nebulae generally appearing to move faster.

Then, in the 1920s, Edwin Hubble began measuring individual stars in these nebulae and eventually determined the distances to them. Not only were they much farther away than anything else in the galaxy, but the ones at the greater distances were moving away faster than the closer ones.

The universe was expanding.

Cornerstones of the big bang theory

Georges Lemaître was the first, in 1927, to recognize this. Upon discovering the expansion, he extrapolated backward, theorizing — as any competent mathematician might — that you could go as far back as you wanted: to what he called the primeval atom. In the beginning, he realized, the universe was a hot, dense, and rapidly expanding collection of matter and radiation, and everything around us emerged from this primordial state.

This idea was later developed by others to make a set of additional predictions:

- The universe, as we see it today, is more evolved than it was in the past. The farther back we look in space, the farther back we’re also looking in time. So, the objects we see back then should be younger, less gravitationally clumpy, less massive, with fewer heavy elements, and with less-evolved structure. There should even be a point beyond which no stars or galaxies were present.

- At some point, the radiation was so hot that neutral atoms couldn’t stably form, because radiation would reliably kick any electrons off of the nuclei they were attempting to bind to, and so there should be a leftover — now cold and sparse — bath of cosmic radiation from this time.

- At some extremely early time it would have been so hot that even atomic nuclei would be blasted apart, implying there was an early, pre-stellar phase where nuclear fusion would have occurred: Big Bang nucleosynthesis. From that, we expect there to have been at least a population of light elements and their isotopes spread throughout the universe before any stars formed.

In conjunction with the expanding universe, these four points would become the cornerstone of the Big Bang.

A dangerous game

The growth and evolution of the large-scale structure of the universe, of individual galaxies, and of the stellar populations found within those galaxies all validates the Big Bang’s predictions.

The discovery of a bath of radiation just ~3 K above absolute zero was the key evidence that validated the Big Bang and eliminated many of its most popular alternatives. And the discovery and measurement of the light elements and their ratios — including hydrogen, deuterium, helium-3, helium-4, and lithium-7 — revealed not only which type of nuclear fusion occurred prior to the formation of stars, but also the total amount of normal matter that exists in the universe.

But extrapolating beyond the limits of your measurable evidence is a dangerous, albeit tempting, game to play.

Extrapolating back to as far as your evidence can take you is a tremendous success for science. The physics that took place during the earliest stages of the hot Big Bang imprinted itself onto the universe, enabling us to test our models, theories, and understanding of the universe from that time. The earliest observable imprint, in fact, is the cosmic neutrino background, whose effects show up in both the cosmic microwave background (the Big Bang’s leftover radiation) and the universe’s large-scale structure. This neutrino background comes to us, remarkably, from just ~1 second into the hot Big Bang.

But extrapolating beyond the limits of your measurable evidence is a dangerous, albeit tempting, game to play. After all, if we can trace the hot Big Bang back some 13.8 billion years, all the way to when the universe was less than 1 second old, what’s the harm in going all the way back just one additional second: to the singularity predicted to exist when the universe was 0 seconds old?

The answer, surprisingly, is that there’s a tremendous amount of harm. The reason this is problematic is because beginning at a singularity — at arbitrarily high temperatures, arbitrarily high densities, and arbitrarily small volumes — will have consequences for our universe that aren’t necessarily supported by observations.

For example, if the universe began from a singularity, then it must have sprung into existence with exactly the right balance of “stuff” in it — matter and energy combined — to precisely balance the expansion rate. If there were just a tiny bit more matter, the initially expanding universe would have already recollapsed by now. And if there were a tiny bit less, things would have expanded so quickly that the universe would be much larger than it is today.

The reason this is problematic is because beginning at a singularity — at arbitrarily high temperatures, arbitrarily high densities, and arbitrarily small volumes — will have consequences for our universe that aren’t necessarily supported by observations.

And yet, instead, what we’re observing is that the universe’s initial expansion rate and the total amount of matter and energy within it balance as perfectly as we can measure.

Why?

If the Big Bang began from a singularity, we have no explanation; we simply have to assert “the universe was born this way,” or, as physicists ignorant of Lady Gaga call it, “initial conditions.”

Similarly, a universe that reached arbitrarily high temperatures would be expected to possess leftover high-energy relics, like magnetic monopoles, but we don’t observe any. The universe would also be expected to be different temperatures in regions that are causally disconnected from one another — i.e., are in opposite directions in space at our observational limits — and yet the universe is observed to have equal temperatures everywhere to 99.99%+ precision.

Cosmic inflation

We’re always free to appeal to initial conditions as the explanation for anything, and say, “well, the universe was born this way, and that’s that.” But we’re always far more interested, as scientists, if we can come up with an explanation for the properties we observe.

That’s precisely what cosmic inflation gives us, plus more. Inflation says, sure, extrapolate the hot Big Bang back to a very early, very hot, very dense, very uniform state, but stop yourself before you go all the way back to a singularity. If you want the universe to have the expansion rate and the total amount of matter and energy in it balance, you’ll need some way to set it up in that fashion. The same applies for a universe with the same temperatures everywhere. On a slightly different note, if you want to avoid high-energy relics, you need some way to both get rid of any preexisting ones, and then avoid creating new ones by forbidding your universe from getting too hot once again.

Inflation accomplishes this by postulating a period, prior to the hot Big Bang, where the universe was dominated by a large cosmological constant (or something that behaves similarly): the same solution found by de Sitter way back in 1917. This phase stretches the universe flat, gives it the same properties everywhere, gets rid of any pre-existing high-energy relics, and prevents us from generating new ones by capping the maximum temperature reached after inflation ends and the hot Big Bang ensues. Furthermore, by assuming there were quantum fluctuations generated and stretched across the universe during inflation, it makes new predictions for what types of imperfections the universe would begin with.

Since it was hypothesized back in the 1980s, inflation has been tested in a variety of ways against the alternative: a universe that began from a singularity. When we stack up the scorecard, we find the following:

- Inflation reproduces all of the successes of the hot Big Bang; there’s nothing that the hot Big Bang accounts for that inflation can’t also account for.

- Inflation offers successful explanations for the puzzles that we simply have to say “initial conditions” for in the hot Big Bang.

- Of the predictions where inflation and a hot Big Bang without inflation differ, four of them have been tested to sufficient precision to discriminate between the two. On those four fronts, inflation is 4-for-4, while the hot Big Bang is 0-for-4.

But things get really interesting if we look back at our idea of “the beginning.” Whereas a universe with matter and/or radiation — what we get with the hot Big Bang — can always be extrapolated back to a singularity, an inflationary universe cannot. Due to its exponential nature, even if you run the clock back an infinite amount of time, space will only approach infinitesimal sizes and infinite temperatures and densities; it will never reach it. This means, rather than inevitably leading to a singularity, inflation absolutely cannot get you to one by itself. The idea that “the universe began from a singularity, and that’s what the Big Bang was,” needed to be jettisoned the moment we recognized that an inflationary phase preceded the hot, dense, and matter-and-radiation-filled one we inhabit today.

The idea that “the universe began from a singularity, and that’s what the Big Bang was,” needed to be jettisoned the moment we recognized that an inflationary phase preceded the hot, dense, and matter-and-radiation-filled one we inhabit today.

This new picture gives us three important pieces of information about the beginning of the universe that run counter to the traditional story that most of us learned. First, the original notion of the hot Big Bang, where the universe emerged from an infinitely hot, dense, and small singularity — and has been expanding and cooling, full of matter and radiation ever since — is incorrect. The picture is still largely correct, but there’s a cutoff to how far back in time we can extrapolate it.

Second, observations have well established the state that occurred prior to the hot Big Bang: cosmic inflation. Before the hot Big Bang, the early universe underwent a phase of exponential growth, where any preexisting components to the universe were literally “inflated away.” When inflation ended, the universe reheated to a high, but not arbitrarily high, temperature, giving us the hot, dense, and expanding universe that grew into what we inhabit today.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, we can no longer speak with any sort of knowledge or confidence as to how — or even whether — the universe itself began. By the very nature of inflation, it wipes out any information that came before the final few moments: where it ended and gave rise to our hot Big Bang. Inflation could have gone on for an eternity, it could have been preceded by some other nonsingular phase, or it could have been preceded by a phase that did emerge from a singularity. Until the day comes where we discover how to extract more information from the universe than presently seems possible, we have no choice but to face our ignorance. The Big Bang still happened a very long time ago, but it wasn’t the beginning we once supposed it to be.

This article was originally published on our sister site, Big Think. Read the original article here.