Supply chain problems and interruptions in public health services caused by the pandemic are threatening recent strides in malaria prevention; one study in Nature predicts that 2020’s malaria burden could double.

Each year there are millions of cases of malaria-borne by mosquitoes, the deadliest animals in history — deadly enough that none less than Anthony Fauci has endorsed wiping them out. Hundreds of thousands of people die every year from mosquito-borne diseases, the majority children under 5 years old, and hundreds of millions are sickened.

Malaria prevention efforts have made great strides in recent years, but there were causes for concern even before the pandemic, including the menace of insecticide-resistant mosquitoes.

To rebuild our anti-mosquito arsenal, chemists at NYU have found that a simple way of processing the common insecticide deltamethrin can hone it into an even deadlier weapon against the pests. Turned into a crystal, the insecticide becomes up to 12 times more effective, knocking down the bloodsuckers fast.

Deltamethrin “faces an uncertain future, threatened by developing resistance of mosquitoes,” the researchers wrote in PNAS. You’ve likely heard of bacterial superbugs, resistant to antibiotics? Well, these are literal superbugs.

Many malaria prevention insecticides come in crystal forms, according to NYU. Sprayed across bed nets and inside homes, crystal insecticides act like tiny, spiky caltrops, sinking in through the mosquito’s feet while they creep-crawl around and killing them.

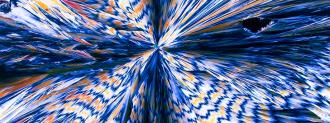

By heating deltamethrin to 110°C/230°F for a few minutes and cooling it down to room temperature, the NYU team was able to form a different crystal, with long, protruding fibers around a central point.

When two types of malaria-bearing mosquitoes — Anopheles quadrimaculatus and Aedes aegypti, if you wanna get Inside Baseball — and fruit flies were exposed to the new crystal insecticide, they died 12 times faster than with usual deltamethrin. Speed is of the essence in malaria prevention; knocking them down quickly means limiting the spread of the disease.

The new crystals also remained stable and effective for at least three months.

“The simple preparation of this new crystal form of deltamethrin, coupled with its stability and markedly greater efficacy, shows us that the new form can serve as a powerful and affordable tool for controlling malaria and other mosquito-borne diseases,” NYU chemistry professor Micahel Ward said in a university release.

As the race continues to find new forms of malaria prevention against ever-hardier bloodsuckers — including mosquito-repellent clothes and GMO mosquitoes — the ability to improve existing weapons can provide an important stopgap.

The pandemic may prove the fragility of those gains.

“Improvements in malaria control are needed as urgently as ever during the global COVID-19 crisis,” NYU chemist Bart Kahr said.

“We need public health measures to curtail both infectious diseases, and for malaria, this includes more effective insecticides.”